By Emily Houston, photos by Douglas Graham

Loudoun County has a long history of strong and conflicting emotions.

Certainly, its divided citizenry during the Civil War (where many remained loyal to the Union) might be one example that could come to mind. But the process of producing a new Comprehensive Plan sparked its share of lively (and sometimes impolite) discourse among citizens as they sought to make choices about what in the county would change and what would stay the same (hopefully).

As plans for growth were made, a spotlight was shone on the needs of the county’s transportation network. Of the 700 miles of public roads in the Rural Policy Area, more than a third (approximately 260 miles) are unpaved. Will they be able to remain that way?

Loudoun’s old roads pre-date America, carved out of the hilly terrain by early settlers who built prosperous agricultural communities in the northern Piedmont. Terrible wars, slavery and the struggle for freedom, the coming of the automobile, and the modern era of commuters living side by side with farmers, all make the history embedded in the roads the tale of a very American experience.

Lined by distinctive stone walls, and cutting through steep banks created by centuries of travel, these roads meander through some of the most spectacular rural landscapes to be found within 50 miles of a major metropolitan area (which just happens to be the nation’s capital).

The crunchy sound of tires rolling over the gravel, whether those of a car, bike, or horse-drawn carriage, evokes the possibility that one can indeed go back in time. Their imperfections annoy some, but their authentic and warm feel, the natural traffic-calming they provide, and the sense of place they add to the county have created dedicated fans.

But the need for this network to function as routes for transportation in the 21st century has highlighted the quandary of how to preserve them as authentic historic assets without succumbing to demands for high-speed, efficient travel.

Loudoun County’s new Comprehensive Plan and the companion Countywide Transportation Plan (CTP) acknowledge the importance of the county’s historic unpaved road network, which (according to the Plan) “…contribute to the character of the rural landscape and provide opportunities for recreational users such as equestrians, bicyclists, and pedestrians.” The CTP notes the roads’ importance in attracting tourists and states that “The county is committed to the preservation of a safe unpaved rural road network.”

Western Loudoun’s historic dirt road known as Millville Road outside of the Village of Bloomfield. Many of the dirt roads in Loudoun are important heritage resources that represent the migration, settlement and travel patterns of the County’s early populations. Historic travel routes are also essential components of the County’s historic landscape as it associates with standing structures, linking early settlements.

The roads, however, are under Virginia Department of Transportation (VDOT) control, and while capital improvement decisions are made in collaboration with the county, the exact process by which roads are selected for paving has remained mysterious.

In the past three years, significant parts of this unique network have been paved, most recently a three-plus mile stretch of Williams Gap Road, which runs along the base of Blue Ridge Mountain, through one of the most scenic stretches of the northwestern part of the county.

Work has started for the paving of Williams Gap road in Western Loudoun that will forever change the character of this historic road. Today, most residents of Loudoun County know nothing about Williams Gap, even those living on Williams Gap Road (Route 711). Knowing who “Williams” was, why a gap in the Blue Ridge Mountains was named for him, and why the rural character of historic Williams Gap Road should be preserved are all significant to our heritage, particularly to those living in Western Loudoun. In the early 1700s, settlers moving west sought farmland along the old Indian trail roads. In 1731, Robert “King” Carter took out a land patent for his 13-year-old son George. In it, the “Indian Thoroughfare” (now Snickersville Turnpike) was described as running from “Williams Cabbin in the Blew Ridge” to the Little River, at now Aldie. The fact that there was a squatter’s cabin at the Gap means that it was there before 1731. In 1743, George Carter owned 2,941 acres as part of the Manor of Leeds “at the lower thoroughfare of the Blue Ridge known by the name of Williams Gap, alias the Indian Thoroughfare of the Blue Ridge, including the same and the top of the ridge.” In 1748, 16-year-old George Washington accompanied George William Fairfax to survey Lord Fairfax’s properties in the Shenandoah Valley. On his return trip in April, he wrote “Tuesday 12th. We set out of from Capt. Hites in order to go over Wms. Gap.” A connecting road from Williams Gap to Leesburg was established in 1764. Known as the Williams Gap Road, it later was called the Leesburg Turnpike. After the Revolutionary War, Edward Snickers’ Shenandoah River ferry was reestablished by the Legislature in October 1786 on “the land of Edward Snickers at Williams Gap.” Later that year Williams Gap became Snickers Gap.

George Washington traveled this route often in his journeys as a surveyor, and it is said that in 1748, he took the road (then called Mountain Road) and became lost. Certainly, we know he didn’t remain so!

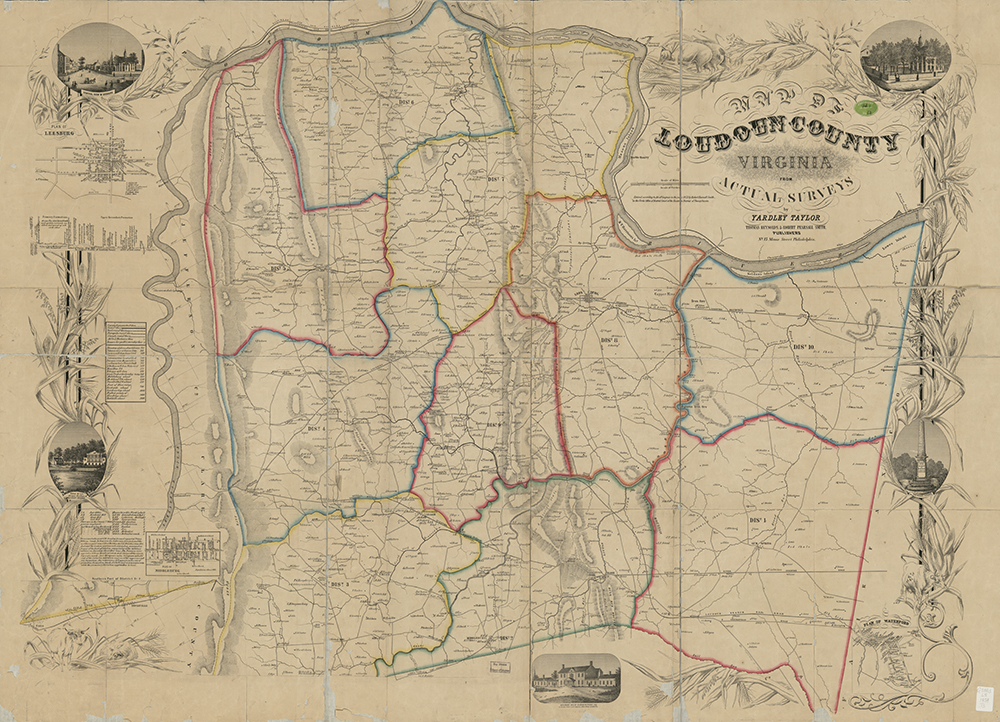

In 1853, Yardley Taylor (a Quaker resident of Lincoln and an ardent abolitionist) drew the first detailed map of Loudoun County, or any part of the Virginia Piedmont. His remarkable work, housed in the Library of Congress, not only identifies all of the County’s roads, but names landowners and occupiers, locates 77 water-powered mills and the many churches and houses of worship that existed at that time.

In 1853, Yardley Taylor (a Quaker resident of Lincoln and an ardent abolitionist) drew the first detailed

map of Loudoun County. His remarkable work, housed in the Library of Congress, not only identifies all of

the County’s roads, but names landowners and occupiers, locates 77 water-powered mills and the many

churches and houses of worship that existed at that time. This map was an essential guide for commanders

during the Civil War, as they moved their troops and supplies, and plotted their strategies. Today, most of

the roads on the Yardley Taylor map are still in existence, proof that the intervening 200 years have not

significantly altered this transportation network. Courtesy of Library of Congress, copyright 1854

This map was an essential guide for commanders during the Civil War, as they moved their troops and supplies, and plotted their strategies. Today, most of the roads on the Yardley Taylor map are still in existence, proof that the intervening 200 years have not significantly altered this transportation network.

The Goose Creek Friends graveyard in the Village of Lincoln. The Religious Society of Friends—“Quakers”—arrived in Loudoun County from Quaker-settled Pennsylvania in 1733, finding that colony becoming crowded with good land in short supply. The Loudoun Valley’s fine soil fit the bill. Initially, Quakers settled some seven miles to the north in and around the village of Waterford, but soon spread out. The Goose Creek Friends Meeting in the Village of Lincoln followed in the 1740s. Quakers, a Christian sect founded in Lancashire in England in the 1650s as an outgrowth of the Puritan movement, believed in the “divine spark” in every human being, regardless of race, nationality, or sex.

As the fastest-growing county in Virginia, Loudoun is now a hotbed of battles between those who seek to preserve its rural landscape and way of life, and the westward march of suburbanization (and urbanization, as two new Metro stops will be opening). A large number of preservation/conservation-oriented groups exist — the Loudoun Conservation and Preservation Coalition serves as the umbrella organization to help coordinate their activities, and currently has 50 member organizations.

Included among them is the Rural Road Committee, which works with VDOT and local politicians to advocate for the unpaved road network. This committee has been successful in lobbying for improved maintenance of the gravel roads, recognizing that the increased traffic this historic treasure is enduring, coupled with the expectations of the growing number of residents living in suburban-style subdivisions, threatens them.

A school bus makes its way along Western Loudoun’s historic gravel road known as Poor House Road. Many of the gravel roads in Loudoun are important heritage resources that represent the migration, settlement and travel patterns of the County’s early populations. Historic travel routes are also essential components of the County’s historic landscape as it associates with standing structures, linking early settlements.

It became apparent, though, that there was a missing ingredient in the efforts to protect this historic asset: a widespread appreciation and knowledge of their history, beauty, and value in the County’s rural life. What seemed so obvious to residents of western Loudoun who already loved their rural roads was not so obvious to many citizens (particularly those living in the eastern suburbs) and politicians.

Thus, “America’s Routes” was born. An informal meeting between two preservationists, an award-winning journalist and a highly-renowned photographer began to surface ideas. Using the talents of a small group of passionate people with expertise in a range of areas, a project to honor the history, beauty, and way of life for which these roads are the backbone was launched.

The America’s Routes project currently has four initiatives:

- Documenting, with photos and videos, the beauty and evidence of history along Loudoun’s rural roads to be archived for future generations.

- Telling the stories of the day-to-day life that continues to unfold on the farms and villages these byways connect, weaving today’s life on the roads with tales of their past.

Allen Cochran moves his sheep along Foundry Road to a feeding pasture using his sheep dogs. Western Loudoun’s historic dirt road known as Foundry Road outside of the Quaker settlement of Lincoln is one of many roads in Loudoun County that are historic. The vast network containing 300 miles of dirt roads in Western Loudoun are important heritage resources that represent the migration, settlement and travel patterns of the County’s early populations.

- Creating an authoritative documentation, road by road, mile by mile, of the road network’s status as an authentic and unique historic asset, worthy of recognition by the Virginia Department of Historic Resources and the National Register of Historic Places.

- Providing tours for visitors to experience Loudoun’s countryside, whether by car, bike or on foot.

Additional components — books, pocket guides, phone apps, a curriculum for history teachers to use, a highly-searchable website making all of the information available in one place — will be possible once funding is secured for these primary projects.

The goal? To create a virtual museum honoring the roads and their role in the history of Loudoun and of Virginia. And to impassion their preservation.

America’s Routes has a website (americasroutes.com) providing samples of some of the work done so far. Tax-deductible donations can be made through the website. America’s Routes is an independent committee of the Mosby Heritage Area Association.

The Long Road Home

America’s Routes Video and Brochure Win Prestigious Awards

In June, America’s Routes photograph Douglas Graham and ABC7/WJLA reporter Jay Korff won an Emmy for their documentary “The Long Road Home” about the America’s Routes project.

“No one with America’s Routes wants to discourage Loudoun’s success. On the contrary, members believe the region’s economy thrives thanks to the county’s bucolic charm,” Korff says in the documentary.

The documentary also won Korff, Graham, and WJLA drone operators Richard Chamberlain and Alex Brauer the prestigious Edward R. Murrow award for Excellence in Video.

Earlier this year, the promotional brochure produced to introduce the America’s Routes project won the Gold ADDY award in the world’s largest advertising design competition. Designer Nathaniel Navratil, writer Danielle Nadler, and photographer Douglas Graham received this recognition.

In March, Douglas Graham won first place for feature photography from the Virginia Press Association, for his work on the America’s Routes project.

Both the video and the brochure can be accessed via the America’s Routes website.

Our family owns a working farm along Rt. 711, and gravel was OK through the ’60s and ’70s when only a car or two came every hour. When large housing developments started to be built in the 80’s, it simply couldn’t handle the traffic volume, large construction trucks, etc. There is nothing romantic or historic about potentially carcinogenic dust covering houses and crops from road overuse after only a few days without rain. Commuters with new cars didn’t like the dust and washboard roads they were creating either, so their complaints had the county here literally every 2 weeks re-grading the road, dredging up even more dust, bringing in dust mitigation trucks, and cutting back into our land to expand the road. “Preservation” can’t mean hardship for those who have to actually drive on what was becoming an unusable road – we’ve paid taxes here for a half century, and deserve safe, modern roads as much as any other Loudoun resident.

As someone who lives on one of these roads, the painted picture of nostalgia in this article is quite contrary to the reality of roads being impassible after a hard rain, congested when two cars cannot pass by each other, and the constant, choking dust of people driving too fast. The people who live on these roads are desparate for modern, paved roadways which are safe and maintained.