And some there be, which have no memorial, who are perished as though they had never been.”

Missy Breeden at her home at the Upper Pocosin Mission in Shenandoah National Park, one of the individuals given lifetime tenure. She died around 1949. Photo courtesy of Larry Lamb

In 1928, the Virginia General Assembly passed the Public Park Condemnation Act, which allowed the Commonwealth of Virginia to exercise its power of eminent domain to acquire private land to create Shenandoah National Park. Some landowners voluntarily sold their holdings while others refused and had their lands condemned. Landowners who had legal title to their property were compensated for the land and improvements. In the end, some 2,000 men, women, and children left their homes and their lands. Some homes rotted, with only stone foundations and chimneys standing as mute reminders of what had been. Some homes were burned to the ground.

After the federal government accepted the donation of park land from the Commonwealth of Virginia in 1935, 43 residents, mostly the feeble and elderly, were given lifetime tenure in the park. The rest made their way to resettlement communities established in the eight counties surrounding Shenandoah National Park, moved in with nearby family, or left the area entirely. Meanwhile, the Great Depression ground on.

When surveyors cut a zig-zag to form the park’s eastern boundary, part of Lisa Berry Custalow’s grandmother’s property on High Top Mountain was destined to become part of the park’s Skyline Drive. When the family refused to sell, the property was condemned, and in 1936, everyone, including Lisa’s mother (who was four at the time), was told to move out.

“Mom wouldn’t talk about it. All she would say is the government condemned the land, we had to move. I wanted to know more, but if I pestered her for more, she got real quiet. It was like the fight had gone of her. But I was ready to fight.” And so Lisa and her husband-to-be, Curtis Custalow, launched a group to advocate for the displaced and their descendants. Lisa named it The Children of the Shenandoah (COS) and held its first meeting in the spring of 1994 at Greene County’s William Monroe High School. COS would go on to meet nearly every month for another eight years.

“We drew 35 or 40 on a regular basis,” Lisa said in a recent interview, including news reporters “who would just show up.” COS had many demands to make of the park, ranging from cemetery maintenance to archives access. But the main goals were to get the park to change its message to the public about how it was created, including changing the content of a short video entitled “The Gift,” regularly shown to millions of visitors each year, as well as reworking how former mountain residents were depicted in the park’s main exhibit at the Byrd Visitor Center.

It was about this time that Germanna Community College history professor Suzanne Crane challenged her students with an assignment to examine the story of the park, as told in “The Gift” and in the exhibit, against interviews with those displaced and still alive.

What happened next was pretty astounding: In November 1994, after meeting with COS representatives, SNP’s then-Head of Interpretative and Educational Services promised that the students’ interviews “will become part of the process of reviewing and revising interpretive media.” Furthermore, the National Park Service authorized a $100,000 remake of “The Gift” and gave it a new title, “Shenandoah: The Gift.” Released in 2001 and still in circulation, this version wholly acknowledges the sacrifice made by the thousands displaced to accommodate the park.

What happened next was pretty astounding: In November 1994, after meeting with COS representatives, SNP’s then-Head of Interpretative and Educational Services promised that the students’ interviews “will become part of the process of reviewing and revising interpretive media.” Furthermore, the National Park Service authorized a $100,000 remake of “The Gift” and gave it a new title, “Shenandoah: The Gift.” Released in 2001 and still in circulation, this version wholly acknowledges the sacrifice made by the thousands displaced to accommodate the park.

The Children’s next victory was the day the park assembled “a dream team of researchers, natural resources specialists, designers, and interpreters [to redesign] the old visitors center exhibit,” as Sue Eisenfeld describes it in Shenandoah: A Story of Conservation and Betrayal. Park staff initially told the story of the mountain communities through a series of revised wall panels that served as a temporary exhibit and hosted focus groups with local organizations to get feedback on necessary revisions. Helpful to the redesign were comments from descendents, local residents, and cultural scientists, including park archeologist Christine Hoepfner, who had served as COS president, as well as another archeologist, Audrey Horning, who worked with the park to unearth and reveal the socio-economic diversity that once marked the park’s people and their communities.

The new exhibit debuted in 2006 at a cost of $250,000, according to Shenandoah National Park. To this day, it allows visitors to see the incredible diversity among former residents of the park lands and dispels former misrepresentations. As Shenandoah National Park Interpretive Specialist Claire Comer noted in a recent interview, the park continues to improve its interpretation of the mountain residents, their story, and their experiences. New outdoor exhibit panels along Skyline Drive expand visitors’ opportunities to connect with the stories of the park’s founding. The park also plans to launch a web-based curriculum targeting middle and high school students that, in alignment with the state’s standards of learning, covers eminent domain and encourages discussion and critical thinking about the park’s establishment story.

Today, many of the Children’s key players have moved on to Gloryland, including Lisa’s husband. Yet Lisa soldiers on with a new focus now initiated by someone who attended nearly every COS meeting but never said a word, not even his name. The Children called him “the hiker.” His name was Bill Henry, and with Lisa’s early help he went on to create a new group, the Blue Ridge Heritage Project (BRHP).

Madison Memorial on Old Blue Ridge Turnpike in Criglersville. by Kristie Kendall

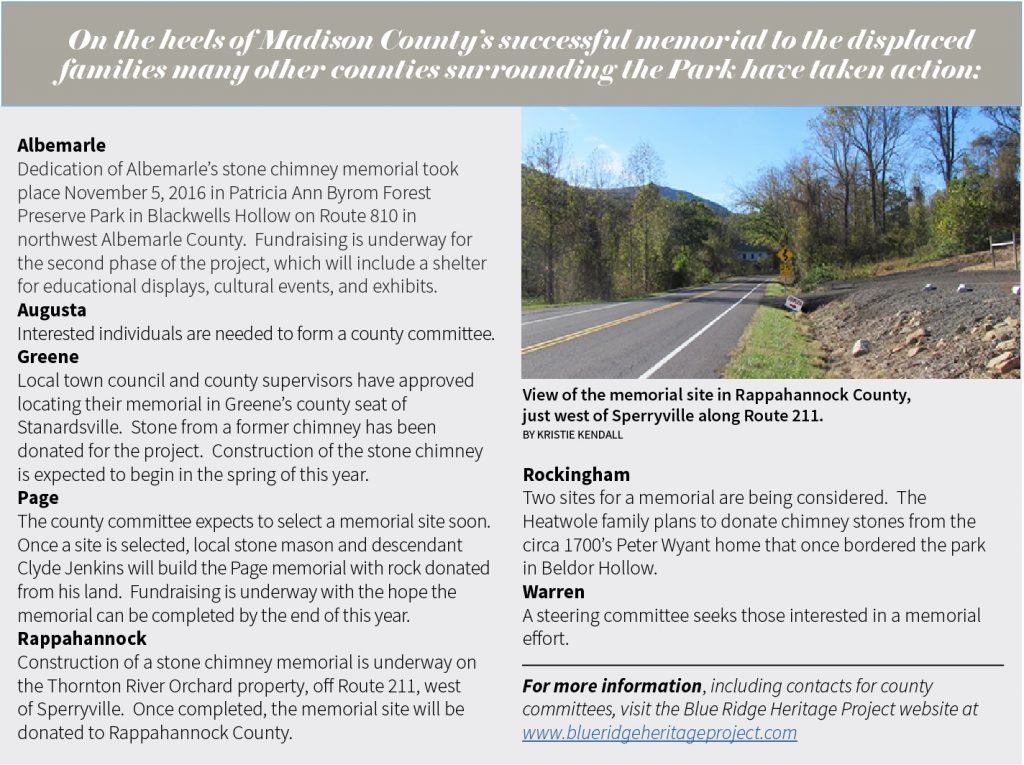

Incorporated in 2013, the BRHP is a nonprofit organization dedicated to continuing the work of honoring and preserving the culture and traditions of the mountain people. For more than three years, BRHP and its board of directors have helped the eight counties where land was acquired to create the park to plan memorial sites to those displaced in each county and exhibits and demonstrations to tell and show visitors the cultures and traditions of the Blue Ridge.

The first fruit of BRHP’s labors came in 2015 as the result of retired VDOT bridge inspector, local historian, and descendant Jim Lillard and his late wife, Linda Yurinak’s, hard work. The pair worked with BRHP and the Madison County Historical Society to get the Madison County Board of Supervisors to allow a temporary memorial on an old Madison school property in Criglersville. Contributions began to pour in from local residents, providing enough funds for the society to design and construct a permanent memorial on the same site. On November 8, 2015, a stone chimney listing the names of 125 displaced Madison families was unveiled and officially dedicated to a crowd of some 300 Madisonians, many of them descendants of the displaced.

“The Blue Ridge Heritage Project is giving long-overdue recognition to the people who were forced to give up their homes and lands to make Shenandoah National Park possible. For so many years, there was a stigma attached to being ‘from the mountains,’ but we are working to bring pride to the families of the former residents and to preserve and pass along the culture and heritage of the people,” BRHP founder Bill Henry said in a recent interview.

Leave a Reply