Tales From the ‘Hollers’

By Kristie Kendall

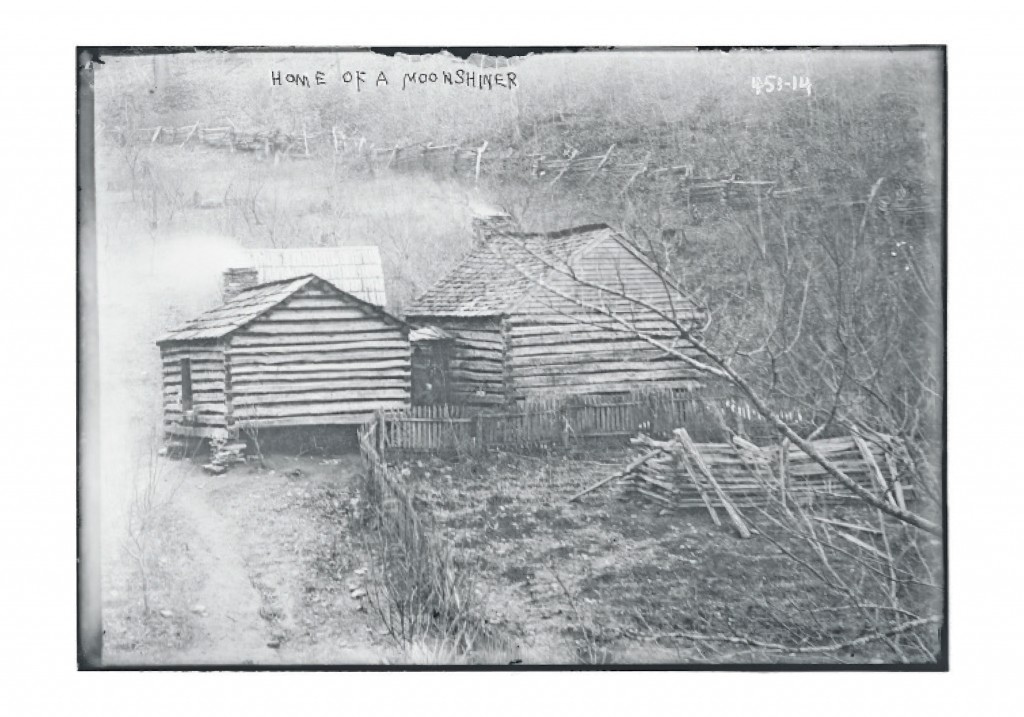

John W. Stoneberger’s mother grew up on Lewis Mountain in Greene County within the hollows of what is now Shenandoah National Park. His grandfather, John Scott Roach was well-known for serving whiskey and brandy in his home, as it was one of his ways of being hospitable to neighbors and a servant of God. Historically throughout Virginia, people made and drank what is often referred to as “moonshine,” although the meaning behind the word has become muddled through the years.

Due to popular culture and television shows like “Moonshiners,” the public’s understanding of moonshine production as a practice often differs from reality. The basic difference between a “moonshiner” and a legal distiller, is that the legal distiller chooses to licenses his operation and pay taxes on what he sells – the “moonshiner” chooses not to.

Historically, the production of liquor has been taxed since the mid-1600s by the British government. In the early 1700s, the British government had an issue with people smuggling brandy on the coast of England and introduced the term “moonlighters” to refer to these individuals. Apparently the term stuck. The United States followed suit with an excise tax from 1791 to 1802. Following the first excise tax, the United States imposed a second one from 1813 to 1817 and in the midst of the Civil War, a high tax specifically on whiskey. By the 1880s, many people were distilling liquor throughout the Blue Ridge Mountains with licensed operations. But the temperance movement was gaining ground. By 1909, many counties in Virginia had banned both the sale and production of alcohol. When Prohibition was enforced nationwide in 1920, the market for true “moonshine” exploded.

Following are reprints of newspaper articles from the Greene County Record, dating from 1922 to 1925. It paints a vivid picture of some residents’ reactions to the Prohibition movement in Virginia’s Piedmont.

_________________________________________________________

Thursday, July 20, 1922

PAT SHIFLETT LOSES RACE IN ALBEMARLE

Pat Shiflett, of Nimrod, Greene County, styled by local police as the King of Bootleggers, has at last been captured. He was taken into custody by Officers Creaver and Marsh of the local police force, after a sensational five-mile run on the new concrete road to Scottsville.

Shiflett made strenuous efforts to escape after being hailed near the southern limits by the officers who saw him in the act of handling liquor containers. He sped away in a Ford car in the direction of Scottsville, with Officer Maurice Greaver hot on his trail. In the flight, Pat undertook to lighten ship by throwing our numerous half gallon jugs of new made liquor, and Officer Marsh got out to salvage the cargo, to be used as evidence against the Greene county flier. The officers, however, only secured four half-gallon jars, the balance of the jetsam being broken.

Officer Greaver finished the chase at Gross’ five-mile post when he forced Shiflett to surrender by covering him with a pistol. On his surrendering he searched his person and found that he bore no arms and then ordered him to drive in front to the police station . . . Shiflett was turned over to the county authorities and a warrant charging him with transporting liquor contrary to the Mapp Act was served on him from the office of Justice Claude B. Yardly. He was admitted to bail in the sum of $500.

Thursday, Sept. 18, 1924

CAPTURE BIG STILL BUT IT DISAPPEARS

Revenue Officers Smith, Alexander, and Fletcher, captured one of the largest outfits in Bacon Hollow, Friday, that was never destroyed in Greene — a 60 gallon still and about 2000 gallons of mash. The still had just been put into operation. They found four men engaged at the still, but only succeeded in making one arrest, George Newman Morris, George Frank Morris, and Grover Shiflett made their escape. Several shots were fired at them and from reports Grover was shot and badly wounded in making his escape.

The 60 gallon still that was captured last week and put in the clerk’s office for safe keeping was taken out through one of the windows Monday night. The worm disappeared Sunday night. If the same party got both parts they have a complete outfit. The still had been slashed and would be easy to identify.

Thursday, May 10, 1923

BACON HOLLOW COMBED FOR STILL WITH RESULTS

Tuesday and Wednesday, Prohibition Agent Brown and 11 deputies combed Bacon Hollow for stills. They searched every suspected house and premises therein. They got eight stills, five gallons and a quart of sugar liquor, and swore out warrants for seven men – Alonzo Shiflett, Moses Morris, Miley Morris, John R. Shiflett, Walter Crawford and Ben Frazier and son – charging them with violating the prohibition law. Several of these men have already been arrested and admitted to bail. A quantity of mash was destroyed by the raiders. The stills and kindred equipment were brought to the county jail.

Thursday, Jan. 12, 1923

PAT SHIFFLETT’S CASE

… Judge John W. Fishburne, in the Circuit Court of Albemarle, next called for trial of the case Commonwealth against Pat Shiflett, indicted on a charge of having unlawfully transported intoxicating liquor in June last and the balance of the day was taken up in disposing of the same.

The case was hard fought from start to finish, Shiflett having employed a strong staff of attorneys in his behalf . . . The case went to the jury after 4 o’clock in the afternoon, every point raised on both sides having been covered by instructions from the Court and fully and ably argued by the astute and experienced counsel for the accused. But the verdict went against him, the jury finding guilty as charged and affixing the punishment of $250 fine and four months confinement in the county jail — the only sentence the liquor vendors dread.

A large crowd was attracted to the Court to follow the proceedings and much interest was manifested in every move of the hard fought legal battle. The prosecution grew out of the sensational chase and arrest of Shiflett June 27, 1923, by Officer Maurice A. Greaver, after a race up the Scottsville road nearly to Carter’s Bridge. The officer had gone over to Moore’s Creek with officer J.C. Marsh after having received a tip at headquarters by phone message from Sheriff J. Mason Smith, that Pat Shiflett had passed him at a rapid rate, coming into town, adding that he might be bringing in liquor.

When the officers spied Pat he was on the level stretch just beyond the bridge and when he spied them, he hopped into his car and got past Greaver, who attempted to head him, and turned up the new concrete road toward Scottsville. They made after him and when only a short distance on the new road, he spied a package by the wayside. On reaching the spot it proved to be a heavy paper carton all tied around with a good string, and containing four half gallon jars of regular bootleg liquor, some having been broken up. This was guarded by officer Marsh, while Greaver made chase after Shiflett in the police car and it proved a fast and furious ride for both while it lasted. But the officer at last got his man covered and gave up and came in.

The defense offered evidence to show that Shiflett had nothing in his car when seen at points beyond the Creek, and even the Sheriff admitted that he was not sure he saw the box as he whizzed by. And the accused man also claimed that he had stopped his car where he was seen by the officers, because of engine trouble. But the jury seemed to be convinced that the liquor was being carried by Shiflett, and that he or his son, who was with him, had thrown it out and rendered the verdict accordingly. The jury on the case were Messrs. W.E. Sheperd, Andrew C. Brown, Ashby Adams, and A.M. Mays. After the verdict was returned, counsel for the convicted man made a motion to set it aside as being contrary to the law and evidence, and upon this being overruled by the Court, noted an appeal to the Supreme Court. A stay for the purpose of filing a petition for a new trial was then allowed to the first day of the February term and Shiflett was allowed to give bail until then in the sum of $2000 . . .

Thursday, May 3, 1923

SHIFLETT CAUGHT AGAIN

Following a tip that liquor was being delivered at a point near Rivanna post office, Sheriff J. M. Smith and Policemen O. M. Wood, and M. F. Greaver proceeded in that direction early Friday night. Without any difficulty the officers quickly came upon Pat Shiflett and son, Pat Jr., who were in an automobile which contained 8 gallons of liquor, and in addition thereto, there was a single barrel shotgun loaded. Both Shifletts were brought here, where charges in two offenses were loaded against them, after they were placed in jail to await a hearing before Magistrate C. R. Yardley.

Pat Shiflett has been a frequent violator of the prohibition laws, and is under sentence for several offenses now. Very recently the supreme court sustained two verdicts against him for fines of $500 and six months in jail, while a third one of $250 and three months in jail is pending before that court on appeal from the Corporation Court.

Thursday, March 8, 1924

JURY IS DISCHARGED IN SHIFLETT CASE

Failing to reach a verdict after being out three hours, the jury in the Rockingham County Circuit Court in Harrisonburg, Feb. 25, trying Dennis Shiflett, of near Elkton, on a felonious assault charge, was dismissed. The jury stood nine to three for acquittal from the first ballot.

Shiflett was charged with assault on Deputy Sheriff W. E. Lucas, after his arrest May 18 last, for transporting liquor. En route from where he was captured in the Blue Ridge Mountains to the Harrisonburg jail, Shiflett’s car plunged off the Shenandoah River Bridge at Elkton into the river 35 feet below. The prosecution contended that Shiflett, was allowed to drive his car deliberately steered his machine off the bridge in an attempt to escape. The defense claimed a faulty steering gear was responsible for the plunge.

Deputy Sheriff Lucas appeared in the courtroom on crutches, not having fully recovered from the injuries he received in the plunge. Shiflett was rendered unconscious and was saved from drowning by the officer holding his head above the water for more than a half hour until rescuers arrived.

Thursday, Oct. 30, 1924

ALBEMARLE OFFICERS FIND LIQUOR PLANTS

Sheriff J. Mason Smith and other officers, while engaged in a raid for discovering liquor Monday night, came upon a plant in an obscure place near Nortonsville, where they found 8 gallons of liquor and about 1000 gallons of mash on land belonging to Ryas Morris. The operators were not found and their identity is unknown.

Quite recently Deputy Sheriff Abbot Smith and Special Agent Plaugher, came upon two outfits in Turkeys Sag mountain, near Stoney Point. The operators made their escape, but one of the men has since been arrested.

Thursday, March 19, 1925

GREENE COUNTY COURT PROCEEDINGS

The Greene County Circuit Court convened at Stanardsville Monday morning at 10 a.m., Judge John W. Fishburne presiding:

A special grand jury was soon selected and true bills were returned on the following charges of violation of the prohibition law:

Commonwealth vs. Henry Lamb, for driving a car under the influence of ardent spirits.

Commonwealth vs. John Iry (Todily) Shiflett, charged with possession of mash, etc.

Commonwealth vs. Lester Morris for manufacturing ardent spirits.

Commonwealth vs. Luke Shiflett for possession of ardent spirits.

Commonwealth vs. Lewis Shiflett for manufacturing.

Commonwealth vs. Charles Herring for manufacturing.

Commonwealth vs. Horton Jarrell for transporting ardent spirits.

Commonwealth vs. Fannnie Bickers for possession.

Commonwealth vs. Nancy Shiflett for possession.

Commonwealth vs. Rebecca Breeden for possession.

Commonwealth vs. Henry Lucas, Jack Zetty, Fred Lawson, George Herring, Ernest Rogers, and Lester Shiflett for impersonating revenue officers.

Commonwealth vs. George Frank Morris charge with unlawful cutting of Myrtle Morris

Remnants of the Ballard Distillery, found along the Moormans River Road in the Sugar Hollow area of Albemarle County (Shenandoah National Park).By Kristie Kendall

Courtrooms overflowed during the Prohibition period as millions of Americans were criminalized for participating in the liquor trade. In Franklin County alone, historians estimate that 99% of its residents participated in the illegal liquor trade in some fashion. In February 1933, Congress enabled states to choose to ratify the 21st amendment, and Virginia followed suit with their own legislation in October of that year. Instead of embracing the act, lawmakers quickly enacted laws to maximize the barriers between Americans and alcohol. The Commonwealth of Virginia voted to create the Alcoholic Beverage Control (ABC) Board on March 7, 1934. Virginia granted ABC agents full police powers in 1936.

Although firm numbers of alcohol consumption during Prohibition are unavailable, evidence suggests it did significantly decrease. However, a comparison of pre and post-Prohibition consumption numbers show that drinking has only risen since Prohibition’s repeal. In 1919, consumption was estimated at 1.96 gallons annually per person and decreased to 0.97 gallons by 1934. Less than a decade later, it had increased to 1.56 gallons and by 1980, was at its all time highest, 2.76 gallons per person per year.

Despite the noted increase in alcohol consumption, the liquor industry is much changed since the early twentieth century. Modern marketed “moonshine” (not technically moonshine since liquor requires licensing to be sold in Virginia ABC stores), is produced with very little grain compared to its early twentieth century counterpart that heavily relied on grain and fruit. Far fewer people are involved in the production of liquor today, than ever before. Despite this, the number of illicit still and production investigations by the Virginia ABC is on the rise, from eight seizures in 2008 to 23 in 2012. The moonshine business, it appears, is still alive and well in Virginia, as it has always been.

About the Author

Kristie Kendall holds a bachelor’s degree from James Madison University in History and a Master’s Degree in Historic Preservation from the University of Maryland. She is a native Virginian and works for the Piedmont Environmental Council, where she focuses on land conservation and historic preservation issues.

Leave a Reply