It’s been almost 15 (now 25) years since an unlikely band of concerned citizens defeated one of the world’s most powerful corporations. But did they really win? The author, an anti-Disney leader, looks back … and ahead.

By Nick Kotz

Like a ghost, Disney’s America—the theme park that almost, but never, was—hovers over the mists and rolling landscape of the Virginia Piedmont. Almost 15 years since the Walt Disney Company announced its controversial plans to create the theme park outside Haymarket, the outcome of the fight still informs and shapes virtually every land-use debate where history, natural beauty, and rural values are at stake—not just in the Piedmont, but around the country.

At the heart of the Disney dispute was whether Virginians really wanted their northern Piedmont to become like Orlando, the Florida city whose sprawling growth was ignited and fueled by Disney World. While the struggle ended in 1994 with Disney’s withdrawal, the retrospective question lingers: by fighting off the development dreams of Disney, what did the Piedmont accomplish exactly?

Growth and sprawl continue to push relentlessly westward from Washington—bringing more of the very congestion that Disney opponents predicted would accompany Mickey Mouse. In the last 10 years, Prince William County alone has added 100,000 new residents, including thousands of families who have settled in the Gainesville and Haymarket areas just east of what would have been the Disney project. Development is inevitable at the edges of any rapidly growing urban metropolis such as Washington. The more relevant question today is how residents of the still semi-rural Piedmont can best manage that growth.

As it turned out, the Disney fight itself actually revealed some promising answers. The victory spawned the rise of a broad-based, determined, skilled grassroots conservation movement. Since Disney, highly experienced citizen activists in Prince William County and throughout the Piedmont have been reshaping Virginia politics from the statehouse to the courthouse. Their efforts today are yielding results. They offer hope for the continued preservation of much of the historic character and scenic landscapes that for centuries distinguished Virginia’s northern Piedmont from the falls of the Potomac River to the Blue Ridge Mountains.

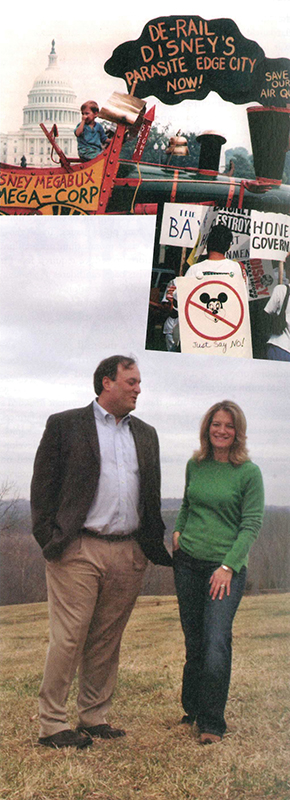

With the Disney fight (and Thoroughfare Gap) behind them, victors survey the field of battle. As a freshly minted environmental lawyer, 28-year-old Christopher Miller, assisted by Hilary Scheer Gerhardt, represented the Piedmont Environmental Council (PEC) and took on Disney. Miller is now PEC president.

The Old Waveland Plantation spreads out over 3,000 acres of farmland bordering the Bull Run Mountains, just north and west of the strategic intersection of Route 66 and Highway 15. There Disney planned to build a 200-acre, $650 million history theme park, where visitors “could get a taste of what life was like during the Civil and Revolutionary Wars.” as well as vicariously experience other memorable moments in American history on an Industrial Revolution roller coaster or a Lewis and Clark raft ride. The park was only a powerful magnet at the heart of a huge real estate development. More than 2,000 additional acres would be dedicated to the development of high-rise condominiums, offices, shopping malls, resort hotels, golf courses, a campground, and as many as 6,000 units of housing. The total effect would have been to create a new “edge city” akin to Tysons Corner—or bigger.

Dazzled by visions of what Mickey Mouse could deliver in jobs and tax revenue, then-Governor George Allen and the Virginia state legislature quickly sealed the deal with $163 million of taxpayers’ money to pay for roads and other infrastructure. A bruising nine-month battle ensued. It pitted neighbor against neighbor; historians and conservationists against developers and earnest citizens hoping for an economic boost.

In the end, Disney abandoned the project, for reasons that we will explore later. Instead, Toll Brothers, the nation’s largest builder of luxury homes, bought most of Disney’s land to develop Dominion Valley Country Club, a gated residential community with schools, commercial shopping, golf courses, trails, and sports facilities. The western end of Disney’s projected domain is still rural, with a 600-acre Boy Scout campground and conference center and with the Silver Lake recreation area.

While Dominion Valley strains surrounding highways and roads, its impact pales besides the stresses that Disney, with its estimated six million annual visitors, would have imposed on the region and its resources. A national urban planning firm calculated that within 10 years the collateral growth generated by Disney’s America would have overwhelmed the Piedmont, much as Disney World has spawned endless development around Orlando. It was that concern more than anything else that sustained the fight against Disney in Virginia.

After Disney withdrew from the fray, then-chairman Michael Eisner attributed the company’s defeat to the power and money of the Mellons, duPonts, and Harrimans, all powerful families with homes in the Piedmont. Eisner’s stereotyped concept of the Piedmont—a foxhunting retreat for the super rich—was ill-informed. He simply did not understand the region, its historical significance, or its diverse population. Eisner did not factor in the talent and skills of the residents of the Piedmont’s towns and countryside, nor did he fathom the depth of their commitment to defend their home.

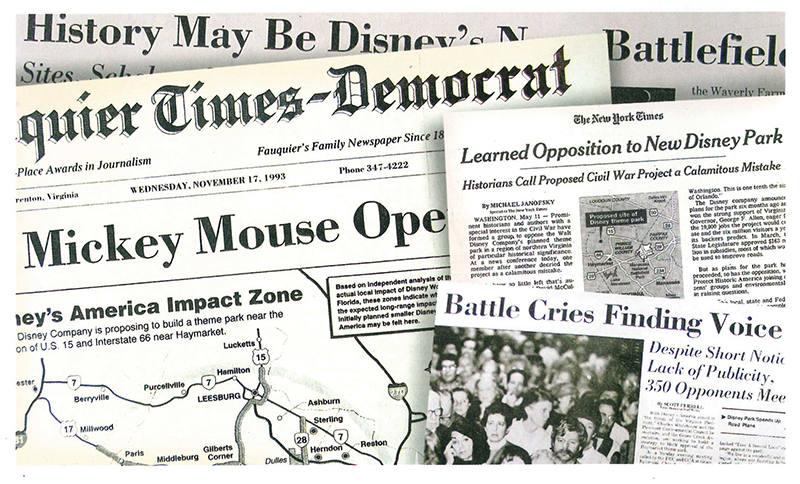

All that talent and commitment were urgently needed after Disney struck in a real estate play, Pearl Harbor style. Acting with total secrecy and in corporate disguise, Disney executives secured options to buy the site outside Haymarket, and started lining up support from Governor Allen and top state and local officials. The Disney announcement in November 1993 took the region by total surprise. With Prince William officials envisioning an economic bonanza to bail out their budget-strapped government, rapid approval of the Disney plan appeared likely.

Five days after Disney unveiled its plan, worried Piedmont residents jammed into Grace Episcopal Church in The Plains to attend a meeting called by the Piedmont Environmental Council (PEC). As they discussed what, if anything, they should do, lawyer and chairman of the Fauquier Board of Supervisors Georgia Herbert, whose Beverley family had lived at Avenel farm outside The Plains for almost 200 years, said: “I don’t know how yet, but we will beat Disney.”

Retired advertising executive Bill Backer suggested the slogan “Disney, Take a Second Look” for an instant advertising campaign that was rolled out on a shoestring budget. Its intent was to slow down the Disney juggernaut long enough for a careful consideration of its proposal and to allow time for opposition to jell.

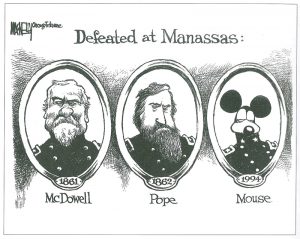

Editorial cartooists around the country often played off the rich Civil War history near the theme-park site and had great fun at Disney’s expense.

Backer is just one of scores of talented Piedmont residents who were first energized by Disney and now lend their time not only to the PEC, but to many other citizen organizations that either first sprang to life or matured during the Disney fight.

In 1993 BD (Before Disney), the PEC was an environmental and land conservation organization with a staff of nine, an annual budget of $350,000, and about 1,000 members. It had never faced a project as daunting as Disney. The PEC received financial help through two duPont and three Mellon fortune heirs, as well as the Chicago-based land planning and conservation foundation Prince Charitable Trust, whose tie to Virginia was foundation president Frederick R. Prince, who loved the Piedmont and had a vacation home here. The work rested primarily on 28-year-old Christopher Miller, who quit a large law firm to offer his services, and 26-year-old Hilary Scheer, a reporter for the Fauquier Times Democrat who had grown up on a Fauquier County farm. Disney chairman Eisner’s portrait of himself as being up against “some of the most powerful families in America’’ with matchless power “to lobby a cause with government” must have seemed amusing to young Miller and Scheer as they tried to counter the army of Disney lawyers, political advisors, lobbyists, and public relations firms.

With Miller at the helm, PEC came of age during the battle with Disney. In the last 10 years, the organization has grown into the premier regional environmental group in the country, a model that others have come to study and emulate. Its membership has soared from 1,000 to 5,000 and its budget and staff have quadrupled. Its ability to mobilize members to their cause rapidly has been perfected. With its 40 staff members working out of offices in nine Piedmont counties, the PEC has since successfully taken on one major environmental and conservation issue after another.

Additionally, the PEC’s activities since Disney include programs aimed at long-term gains in conservation protection. The amount of land in Piedmont counties protected by scenic or conservation easements has quadrupled from 76,000 acres to nearly 300,000 acres—the single largest concentration of easement-protected land in the nation

The western end of the envisioned theme park area remains rural with a Boy Scout campground.

Experts were needed to lead the charge, but the Disney battle and subsequent fights would have been lost without the skills and dedication of veteran community organizers. When Disney announced its plan, the PEC lacked the infrastructure and experience to mobilize members rapidly. The pioneering work of veteran organizers was critical, and was shouldered by Warrenton’s Hope Porter. When Disney officials showed up for the world premiere of the Lion King at Washington’s Uptown Theater, Porter organized a protest with dozens of participants waving signs, local puppet artists with effigies of “Mickey the Rat” and “the Lyin’ King”, and children chanting “Hey hey! Ho ho! Mickey Mouse has got to go.” At an event at the National Zoo, she even managed to decorate Eisner’s limousine with a “Disney Take a Second Look” bumper sticker. She also commissioned a small plane to pull a banner saying: “Governor Allen, Don’t Sell Out Virginia” at the May 1994 Gold Cup before a crowd of 50,000. In the summer of 1994, several thousand protesters from Prince William and the other Piedmont counties staged a “March on Washington,” parading past the White House, around the Capital, and ending in front of the Washington Monument. Demonstrators included farmers, teachers, carpenters, lawyers, and other locals, all carrying protest signs with slogans like “Disney Destroys Farm Land,” as well as a cardboard coffin with the name “Michael Eisner” on it. Porter was joined by the late Annie Snyder, who reenergized the Save the Battlefield Coalition. Working together, Porter and Snyder collected 40,000 names on a petition opposing Disney that they circulated to conservation groups, garden clubs, and Civil War organizations throughout the nation.

Stirred by the Disney fight, Piedmont citizens now meet in dozens of new grassroots groups, unifying through umbrella organizations such as The Coalition for Smart Growth. Chris Miller and 17 other leaders of the Virginia Conservation League came together in conference calls twice a week to compare notes and coordinate their actions on state policy issues. This collaboration set the framework for today’s efforts, when issues range from maintaining a state moratorium on uranium mining to opposing the reduction of new development fees.

These grassroots efforts have paid dividends. In Prince William, the board that uncritically cheered on Disney was replaced with supervisors attentive to conservation supporters. Effective new citizen groups include Advocates for the Rural Crescent, the Rural Preservation Alliance, and the Prince William Conservation Alliance. Responding to citizen demands to protect open spaces and carefully plan growth, the board created an 80,000-acre rural crescent at the western end of the county to limit development there. In 2003, Prince William Board Chairman Sean Connaughton declared that the county was better off economically than it would have been with the Disney theme park. “We’re finally starting to break ourselves out of being completely dependent on a service economy and moving into the high-tech and bio-tech worlds” he told The Washington Post. “I don’t think we ever would have done that if Disney became the driving force in the economy.”

Where Disney would have been: Dominion Valley Country Club, a gated residential community with its own schools, retail centers, golf courses, and other luxury facilities, developed by Toll Brothers, one of the nation’s biggest builders.

In Fauquier County, the board of supervisors is actively promoting land conservation by spending county funds to buy “development rights” from farmers to help keep land in agriculture. Former Governor Tim Kaine also pushed hard to protect more agricultural and forest land from development.

By early spring 1994, PEC and its allies had battled Disney for six months with mixed results. They had challenged Disney’s rezoning application with every available federal, state, and local requirement for zoning and environmental and conservation protection. Disney had been forced to refine the details of its proposal. Yet final approval by the Prince William government of the Disney project seemed inevitable. A drawn-out, costly legal fight—most likely ending with Disney as the victor—loomed ahead.

At this critical point, Fauquier resident Mary Lynn Kotz, an author and former magazine editor, fastened on what she had decided was the missing element in the Disney fight. None of Disney’s opponents had effectively publicized the most valuable and best-known resource in the Piedmont—its rich history!

This history of the Founding Fathers and of the Civil War was a common heritage shared and valued not only by local residents, but by people throughout the nation. Yet the Disney fight had been waged like any other conventional zoning dispute, pitting land conservationists and environmentalists against developers. Americans outside of the region needed to be made aware of their stakes in the issue.

On a misty spring night, four of us decided to put history on the front burner. Meeting in the parking lot behind the Fauquier Middle School, Mary Lynn Kotz and I, and old friends Julian and Sue Scheer, decided to start a new front to engage the entire nation in the fight to protect the Piedmont. We would ask the country’s most distinguished historians and journalists to remind Americans everywhere that the Piedmont was not just our home, but was home to Presidents Washington, Jefferson, Madison, and Monroe and the scene of the most bloody fighting of the Civil War.

The next day, we created Protect Historic America. Within a month, we had recruited 200 of the nation’s historians and writers to serve on Protect Historic America’s national advisory board, including veteran journalists Bob Walters and Rudy Abramson, president of the National Trust for Historic Preservation Richard Moe, author David McCullough, and Civil War historian James McPherson. With the help of former Reagan campaign manager Peter Hannaford and attorney and history buff Harry McPherson, we introduced them and other board members at the National Press Club. The conference was attended by the nation’s major news outlets and networks.

In a matter of days, the dispute about Disney’s proposed history theme park had become national news. The late C. Vann Woodward, dean of American historians and co-chairman of Protect Historic America, described the Piedmont’s essence: “This part of northern Virginia has soaked up more of the blood, sweat, and tears of American history than any other area of the country,” he wrote in The New Republic. “It has bred more of the Founding Fathers, inspired more soaring hopes and ideals, witnessed more triumphs and failures, victories and lost causes than any other place in the country.” Woodward, David McCullough, and the other historians feared that Disney’s sprawl would despoil the Hallowed Ground’s battlefields and destroy the open landscape and historic buildings from the Virginia of Thomas Jefferson’s time.

Politicians from other states, newspaper columnists, editorial writers, and cartoonists joined the cause. In four months, the files of Protect Historic America accumulated 15,000 news articles, editorials, and cartoons, several of which portrayed a sad President Lincoln wearing a Mickey Mouse cap. Television coverage reached Europe and Japan, whose representing reporters were guided around the endangered battlefields by advisory board member W. Brown Morton III.

Growing irritated by the mounting volume of criticism, Eisner lost his temper. In a series of incidents, he told CBS that Virginians “should be so lucky as to have Orlando in Virginia” and The Washington Post that he had expected “to be taken around on people’s shoulders.” He followed by deriding his historian critics: “I sat through many history classes where I read some of their stuff, and I didn’t learning anything. It was pretty boring.” Looking back, Eisner would lament how his imprudence had hurt his own cause.

In late September, Disney announced it was pulling out of the Piedmont. In the new barrage of public criticism, Disney executives decided that even if they won approval for the theme park, it might become a Pyrrhic victory. Having suffered from the lampooning of its treasured trademark symbols, Disney decided not to risk the serious, perhaps permanent, damage to the company’s reputation.

In the Piedmont today, there is a new pride of place in the nation’s history. Fauquier resident Janet Whitehouse led the effort that created the Mosby Heritage Area, an educational program to provide awareness of the cultural and historic resources of the northern part of the Piedmont. Local governments, led by Fauquier County, are commissioning studies of their counties’ history and adding more sites to the National Register of Historic Places. Protect Historic America executive director Rudy Abramson celebrated region’s history and preservation in Hallowed Ground: Preserving America’s Heritage. A new organization, Journey Through Hallowed Ground, is working to imprint the region’s historic identity along the route from Charlottesville to Gettysburg.

“The most significant effect of the Disney fight,” said PEC President Chris Miller, “is that it told people that they could fight back—and win!”

Postscript 2017:

Almost 25 Years After the “Third Battle of Manassas”

As this article from 2008 mentions, some of the best thinkers in conservation and historic preservation came together to fight Disney. And they won!

“Beating Disney showed the entire nation that a grassroots movement is capable of taking on the Goliaths of the world,” says Chris Miller, president of the Piedmont Environmental Council.

Since the colossal theme park never made it to Haymarket, Miller says he is asked about the large-scale residential and commercial development that has occurred in the area.

“I’m approached with a hard-hitting question: Do I believe that Northern Virginia and the Piedmont really won the fight? And I understand the frustration some feel as they drive past thousands of houses on either side of Route 15 and the Wal-Mart shopping center. But my answer is unequivocally, ‘Yes!’ ”

The level of development in and around Haymarket today is consistent with what was planned and zoned for the area before Disney announced their plans, according to Miller.

“Our concern was that Disney would attract even more sprawl in the surrounding region—as has occurred with their other parks. If Disney had come in, we wouldn’t just be dealing with the development in Haymarket, but a 20–50 mile radius of impact that would have swallowed up much of the Northern Piedmont,” says Miller.

Post-Disney, there’s been increased engagement and empowerment of Prince William County residents who continue to battle to preserve the Rural Crescent, with assistance from groups such as Prince William Conservation Alliance, the Coalition to Protect Prince William County, and the Coalition for Smarter Growth.

–Paula Combs, Piedmont Environmental Council

Leave a Reply