A powerful essay about longtime healing and refuge in Fauquier County by author James Reston, Jr.

The cabin at Fiery Run by Helen Costello

I’m sitting in my cramped, knotty-pine office at the cabin in our splendid isolation, pondering the beautiful things. The first humming birds have arrived, and our old friend of years past, the phoebe, has returned to build her nest and raise her chicks over our porch floodlight. She flits her tail feathers in greeting as much as for balance. And my favorite, the clown, the garish red-headed woodpecker, is back.

Last night, about 4 a.m. Posie barked, and we snuck downstairs with a flashlight in hopes of seeing the culprit that had been destroying our fancy bird feeders. And there he was, perfectly framed in our picture window, lumbering toward us. He was big! and fat, and he did not flinch when I splashed him with a beam of light. He swayed his enormous head from side to side indifferently, feeling, it seemed, entirely at home. Is he habituated? we wonder. As he waddled off into the darkness, we decide to call him Mortimer Snerd.

But this morning we quickly lose our fuzzy sentimentality. The beast had utterly pulverized three cherished blue bird boxes, had overturned wooden benches and lawn chairs, and had carved an enormous divot in the roots of our distressed Sycamore tree on the lawn. It was as if he had been in the grip of some primal rage. As a final insult, he left an enormous scat pile speckled with our bird seed. We remind ourselves that a bear is an apex predator, not a nice fellow at all, and needs to be given a wide birth. This was truly one bad news bear. We will be bringing our bird feeders indoors at night from now.

There have been only—only!—five deaths in Fauquier County so far. In Rappahannock County, there are twelve cases of the disease and no deaths. As I write this, Hillary, our most vulnerable one, is asleep and snoring on the living room couch. We feel safe here and content to ride this thing out in situ. I congratulate myself for not being distractible, as are so many of my friends. I have a book to write.

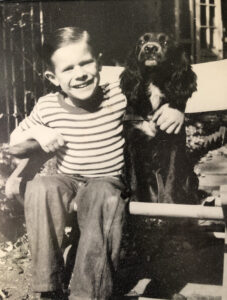

Right before my bus accident

Family letters have been stashed out here forever, and there’s time now to focus on family. This morning, I open an old manila folder, brush away a stink bug and a dead fly, and come upon a letter dated May 12, 1947. It’s from my dad to the editor-in-chief of the Boston Herald. “Fortunately, Jim is better,” it reads. “There is perhaps another anxious week of waiting to make sure that the cracks in his skull develop some protection of their own.” The cracks in his skull. The phrase jumps out at me. It has been the butt of many bad jokes over the years. The letter goes on to describe my accident: how as a six-year-old I wandered down 34th Street in Georgetown, crossed busy Q Street to the small pocket park, and stood on the bank above the ball diamond to watch a soft ball game. There was a foul tip, the ball arced toward me, and smacked me square in the face. Half blinded and squalling, I turned around to bolt home, stepped onto Q Street and was struck by a city bus.

These decades later I remember only my eyes flickering open for just a second, in the back seat of some Good Samaritan’s car. I’d been scooped up and driven to Georgetown Hospital. “The bus hit him dead on,” the letter continued. “and after one bounce he fell.” Bystanders were shouting at the confused bus driver to go either forward or backward. “By the grace of God, the bus passed over him without the first wheels hitting him. Jim was lying under the bus about a yard in front of the double rear wheels, and that yard undoubtedly saved his life.”

I had suffered ten fractures of the skull, one running dangerously toward the sinus. The doctors worried about a hemorrhage that could cause an infection that might race to the brain. But I survived, and after weeks in the hospital, I finally came home. Somewhere there’s a picture of that convalescence. A crooked little body and swathes of wide gauze wrapped around my head like a casualty of the Spanish Civil War.

Both my mother and father were out of town on the day. Mom was attending to her ailing father in Chicago, and Dad, against the rules, had flown to New York for the day to attend a session of the United Nations. Beyond their shock and grief, there was, I suspect a major element of guilt. They had a pact that they would never be out of town at the same time. Later, Dad lamely pleaded that he was, after all, only going up to New York for the day.

In the aftermath they were determined to “get the boys out of town to some safe place far away from the city streets.” After a wide search they found Fiery Run, an 11 acre parcel in the foothills of Blue Ridge Mountains of Virginia, surrounded by the 3000 acre estate of a Belgian countess. She was a Rothschild by marriage, her husband having been part owner of the Bank of Belgium, before he had been swept away by the Nazis. She escaped to Fauquier County.

By the side of its aptly named, vigorous stream there was a stone mill that had served the community in the 19th century well into the 20th. The ruin of its walls still stood, and next to it, the sturdy house of the miller, built in 1820, not far from the gravel road and a metal one-lane truss bridge. Across Fiery Run and over a three-acre pasture, up a hill, four walls of an abandoned log cabin with no roof beckoned. Before it became the miller’s blacksmith’s shop, it had been a slave cabin. Just up the gravel road a lone chimney stood in a cow pasture, the lone remnant of the shack where Robert Ford was raised, “that dirty little coward” as the 19th century folk song goes, the man who assassinated Jesse James.

They bought the place for $3400 with mortgage. A Warrenton architect found another abandoned cabin somewhere in the mountains, and joined the two together. For years the dual cabin had no running water or electricity. When I was strong and well enough after my accident, it was my job to carry out the honey pot from the airplane toilet and pour its contents into a lime pit down the lane. It took a lot of work to make the cabin livable. Along the way my mother was to remark that she was just carrying on the old slave tradition.

Two years later when I was eight, the cabin had its first stint as a refuge. I’d been shipped off to Minnesota for a summer camp. A few weeks after I’d arrived there, polio broke out at the camp, and I had been exposed. In the late 1940s this was every parent’s nightmare, as fear of the highly contagious infantile paralysis gripped the country. The virus was at its peak in those years before 1955, the year Dr. Jonas Salk discovered the polio vaccine. Tens of thousands of children were infected; thousands horribly crippled, and thousands more died. In the papers there were pictures of children encased in that grotesque cage called an iron lung, little heads sticking out of a metal tube as if they were being cooked.

Soon enough, my favorite uncle stood before me, requesting that I pack my trunk quickly, for we were going for a fun ride. He was a tall, strapping man, who had been a champion gymnast at the University of Illinois and a World War II veteran. Then a reporter for the Chicago Tribune, he had my mother’s wonderful smile and sense of fun. He had rented a small plane to fly up there to pluck me out. That my uncle, apart from his other manly attributes, could actually be the co-pilot of an airplane made his heroic status soar even more.

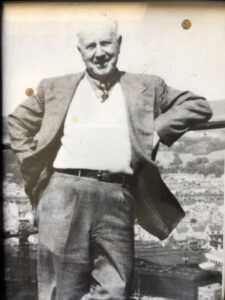

Grandad Reston, my minder during my polio quarantine

I was brought to Fiery Run for an extended quarantine. My 77 year old grandad on my father’s side had stepped forward volunteering to mind me. He was a small, nimble, vigorous Scot with a ruddy face and wispy white hair. He was glad to serve the family and accept the risk, he told my folks, for he professed to have already lived a good life. It was not true. He had toiled and sweated in the Glasgow ship yards for years, before he emigrated to the U.S. in 1909. Settling in Dayton, Ohio as the vanguard of his family, he had been a machinist on the assembly line at the Delco Battery Company. After World War I my grandmother came over with my dad and his sister, passing through Hoffman Island in New York for quarantine and vaccination against the Spanish flu pandemic which had infected one third of the world’s population at the time and killed nearly 700,000 people. But life as a factory worker had hardly been a picnic, no matter what he represented to my parents. He may have been the hardest working man I ever knew.

During those months of quarantine, my folks would show up at Fiery Run occasionally with provisions and clean clothes which they would hand over the fence on a long stick, and we would hand back my dirty clothes which, no doubt, they took home and boiled in lye. Grandad was a tireless worker, landscaping the lawn and tending his perfect garden. The sheep on the hillsides reminded him of Scotland. In the evening he sat on the porch humming Presbyterian hymns. The time was filled with tasks and rural delights. Once I joined the countess’s shepherd and watched in awe as lambs were born. I took my daily dose of large round pills the size of jawbreakers. It was a happy isolation.

There is a tragic anecdote to this episode. Two years later Uncle Bill had moved to New York as the Tribune’s UN correspondent and lived in Cos Cob, Connecticut. One evening after his commute home from the city, he went for a summertime swim after dark in the Long Island Sound, got a chill, and contracted polio himself. Several years later I visited him in Cos Cob. That once tall, athletic, heroic man was now bent and twisted, lurching forward on two canes as he labored in his garden. But he still had that wonderful smile and impish sense of humor. I have often wondered if I bore some responsibility for his exposure.

In 1982 when I had become a writer living in New York, I had the opportunity…and the honor…to interview Dr. Jonas Salk for a magazine article. Sitting before the inventor of the polio vaccine with a decided awe, I was sure he’d be bored to hear the story of my quarantine and my Uncle Bill’s tragedy. How many such stories had he heard? After a while, such sad stories must acquire a dull sameness. He then presided over the Salk Institute for Biological Studies in La Jolla, California, and his mind and his Institute had moved to questions of cancer research, population control, world poverty and nuclear conflict. The industrialist, Armand Hammer, was then offering a $1 million reward for any scientist who could come up with a vaccine for cancer similar to what Dr. Salk had done for polio. The Salk Institute was thought to be a contender. But Dr. Salk was scarcely riding on his laurels. He had become deeply interested in the philosophical, psychological, and social consequences of biological research. He believed the world was moving into a new epoch, in which there needed to be a wiser approach to human evolution. “I have begun to see things in a global way,” he told me. “to see the world as a whole, not just in numbers but in quality.”

******

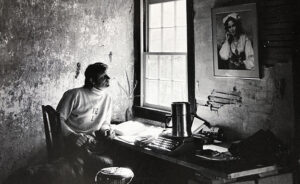

Working on my first novel after my release from the army

The half-year spent at Fiery Run after my three years in the army was also a kind of convalescence. My hitch between 1965 and 1968 coincided with the steep escalation of the Vietnam War. By my last year in the service, it was clear that the war was a disaster. Body counts and pointless assaults on forgettable hamburger hills and most of all, the Tet Offensive in January of 1968 pointed to the abject failure of the whole enterprise. I had become increasingly uncomfortable with my tiny part in it all. I’d been living in a bubble for three years and I was coming home to a country that was intensely hostile to the Vietnam veteran. And so Fiery Run was the perfect retreat and refuge that might afford the time to readjust to civilian life.

In that last year in the Army when I was stationed in an intelligence unit in Pearl Harbor, I began to write a novel. I would fly off to an outer island on the weekends and hole up in a hotel room to write. I was not the worst case. I was not suffering from PTSD or combat fatigue or shell shock. But I thought a novel might be a good way to work out my ambivalence and my alienation.

I’d never written fiction before, but whatever literary shortcomings the work may have had, deep feelings made up for them somewhat. A close friend with whom I’d trained had been killed during the Tet Offensive. His letters to us spoke glowingly of his post in a small villa on Ly Thuong Kiet Street in Hue. He was excited about his important work. I envied him his assignment, as I dithered and dallied at my desk job in Hawaii. His missives had a touch of Graham Greene in them, and Ron Ray was a bit like Aiden Pyle in Greene’s novel, The Ugly American. But intelligence from the MACV compound two blocks away about a coming NVA offensive had not filtered down to Ron’s villa. His death was pointless. He had not fired a shot. His death affected me deeply. I needed space and quiet and yes, isolation, to digest it.

In 1969 as the war still raged and the casualty rate still soared, it was too soon for a Vietnam novel—1975 and beyond was the prime time for the genre. It was widely rejected in New York. But there was one positive response. A young editor at Viking had written me an encouraging rejection letter and offered to sit down with me to discuss its shortcomings.

Before I left my country retreat to drive to New York in September 1969, a story broke about a covert green beret operation that had discovered a double agent in its midst and had eliminated him “with extreme prejudice,” i.e. they had drugged him, wrapped him in chains, put him on a boat, where they shot him in the head and dumped his body in the South China Sea. The story had leaked outside of the chain of command, and six men were charged with premeditated murder. To my shock I read that Staff Sergeant Alvin L. Smith, Jr. was one of them. He had been the agent’s handler. I had served with “Pete” Smith in my intelligence unit in Hawaii, and I knew him well.

To my further anger I read that the CIA was denying all responsibility for the incident. In an August 16 dispatch in the New York Times, the agency was quoted as asserting that “the agency had a strict policy of neither ordering, suggesting nor condoning assassinations. The CIA had no current authority over Defense Department personnel and therefore could not ‘order’ an assassination.” I knew this to be a lie. It was a blatant coverup. All lathered up, I sat down at the cabin and wrote a letter to the New York Times.

“It is unthinkable that any covert operation could be run by the American military without the approval of the CIA,” I wrote. “Likewise, it is unthinkable that any severe termination with prejudice could be carried out without CIA’s approval, unless clear standing orders were disobeyed. It is amazing that the Army arrested these men for what has been modus operandi in the game of intelligence for years.”

As I wended my way to New York, further reporting revealed that it had been Pete Smith himself who had opposed the assassination and had reported it to higher authority. Now in that company of killers, he feared for his own life. On the day my letter appeared in the Times, October 1, 1969, President Richard Nixon ordered that all charges against the murderers be dropped. The coverup was complete.

Crestfallen but not surprised, and dispirited from my bittersweet editorial conference, I drove back south, opened my mail box by that gravel road. Inside was a telegram. “Any chance of a book to follow your most interesting letter in the New York Times?” It was signed Evan Thomas. How could I know at that exhilarating moment that he was the legendary editor who had edited the authorized biography of JFK that had caused so much trouble?

The novel was published in 1971. That same year, on the lawn of the cabin at Fiery Run I married a Bronx girl who has entertained and delighted me for the 48 years. She was 23 then, wispy and feisty and street-wise, and I was a seasoned 29. When she tried on a wedding dress at Bonwit Teller and the clerk adjusted a white veil over her face, she had fainted dead away. The clerk allowed that this was not the first time that had happened. If she was dressed traditionally at our wedding, I wore a white turtle neck and a Hawaiian lay and blue bell bottom trousers, as if I was trying to make some sort of a statement. We read poetry to one another, I from John Donne: “I scarce believe my love to be so pure…” and Denise from e.e. cummings: “be unto love as rain is unto colour, create me gradually….” Rabbi Sam Schrage from Crown heights in Brooklyn who had been our shadchan gave the Lesson. When I was to place the ring on her finger, the script called for her to read from the Song of Solomon. Set me as a seal on your heart…” This time, she delivered her lines capably and did not faint.

Getting hitched

It was all a very 1960s affair in the early 1970s with bridesmaids in long paisley dresses and barefoot sitting on hay bales, listening to a country music band called Virginia Gentlemen, playing on the porch. Katherine Graham was in attendance. Later in her Personal History she referred to the wedding as “casual.” Naughtily, late in the day, my dad whispered to her that the Times would be publishing the Pentagon Papers the next morning. In the packed living room of the cabin, with rain starting to fall outside, there was only one telephone, and there was no way she could commandeer it to call the Post about her competitor’s scoop.

James Reston of the “New York Times” and Katherine Graham at my wedding.

Whispers about the Pentagon Papers.

In his columns in the New York Times during the 1970s and 80s, my father wrote an occasional column with the dateline, Fiery Run, Virginia. There is, of course, no town or village in Virginia called that, and so his musings seem to spring from some magical, idyllic hideaway. He noted that somehow these homespun columns got more reaction from readers than “most of my solemn epistles on the passing tangles in Washington.” They were often filled with mirth and self-deprecation. He referred to himself as a “certified mechanical incompetent.” His tomato plants always seemed to contract spotted fever, he moaned, and grew no larger than walnuts. One memorable column was a letter to the Burpee Seed Company. “To be honest about it”, he wrote, “I don’t see much hope of that ‘great tasting, fresh nutritious food’ you talked about which would, as you said, help our ‘household budget.’ Considering the cost of the garden tractor ($800) we had to buy, the roto-tiller, ($300) ”Farmer Fred, the Friendly Scarecrow” and other ”essentials,” such as your ”Green Thumb Gloves” (No. 9132-2), our supply-side budget has a larger deficit, per capita than David Stockman.”

As my folks got older, managing the place began to be more of a chore. “Just as we got the place all neat and clean,” dad said. “It was time to go back to town.” My mother was terrified of snakes, and she didn’t much like mice and flies either. They let me know that I should take a greater interest in the place or else, God forbid, they would consider selling it. And so in the late 1970s I would drive up from North Carolina where I was teaching creative writing at the University with my lawn tractor in the bed of my old pickup truck. Nevertheless, he passed the property on to my care wistfully.

“The solid hills of Virginia seem to me eternal and peaceful,” he would write, “and I plan to spend a lot of time there in the next couple hundred years.”

******

Hillary is still sleeping soundly downstairs as I ponder all this. No seizure yet today. Her story is too bound up with the cabin. We had a video conference with her doctor yesterday about how to protect her as the economy opens up and we try to restore some variety to her life. With her underlying illness, she falls into the highest category of risk.

Her story in a nutshell is this. After ten years in North Carolina we moved to New York with two toddlers in the fold before Hillary turned up at New York hospital. But despite some modest successes in my professional life, Brooklyn had become too expensive for us, and we bailed out once more for the refuge of Fiery Run. The winter of 1983 turned out to be the coldest in recorded history. Our porch thermometer registered eight below zero that January. We shut off the living room at the cabin and huddled around the wood stove next to the kitchen. When we could get out, I tamped down snow on a far-off slope with the jeep for a glorious long run for the kids.

Hillary’s routine was to sit by the picture window and comment on the birds. She was, up until 18 months, the most verbal of our children with perhaps as many as 200 words. I was working on a play and thinking theatrically. One day Hillary wandered into the kitchen and then reappeared in the frame of kitchen door as if it was a stage set from which the main character would make her first appearance. But this was a horror show. She shook and dropped to the floor with her first seizure. We rushed her to the country doctor in Marshall who acknowledged that there was something odd about her “swoon.” It was a romantic word, suggesting the Old South, but there was nothing romantic about this. Her seizure condition has persisted for 38 years. As we understood it then, an infernal virus had breached the blood barrier of her brain and attacked its language center. We watched her lose her words one by one, dwindling to the word ‘birdie,’ until there were none.

Mowing the pasture with Hillary

That alone might qualify her now for that phrase we hear a lot, the vulnerable with “underlying health conditions.” But her intractable seizures are not how the coronavirus threatens her most. Three years later as we came to the top the lane to the cabin, I looked at her in her car seat to notice how puffy she looked in both her face and her belly. It was the onset of the second major assault on her body. Perhaps caused by the valiant, aggressive efforts to control her seizures, her kidneys were failing. It would take another eight years before they failed completely, and another eight years after that on daily peritoneal dialysis before she got that miraculous transplant in Iowa. By virtue of having to take anti-rejection drugs every day, her immune system is suppressed; her resistance to disease is weak. The medicines she must take to avoid rejection tamps down her body’s immune response to any foreign invader. If she were to be exposed….I don’t want to think about it.

The medical explanations do not encompass the emotional side: the love we cherish for her, nor do they describe the way she spreads joy in the community wherever she goes. I’ve read somewhere…and I believe it…. that people like her are the closest to the angels. She has become the heart of our family. Her doctor said to Denise recently, “You have done well to keep her alive this long.”

And so we are again at Fiery Run, this magical place of calm and solitude. My bus accident, my polio scare, to my transition to civilian life, my launch as a writer seem to pale in significance next to this current situation. As much as we are treated by wonderful natural things, nature everywhere is suggesting upsetting metaphors like the rage of that destructive bear. We climb on our beloved 1950s tractor we call Big Bertha. I put Hillary on my knee, and we begin to cut the pasture. I wince when I look at the ash trees in our woods that are blonding out and dying from ash borer disease. Thousands of these ash trees are dead and dying up in the Shenandoah National Park. We have already lost all our locust trees from a raging root fungus. I scan the skies for raptors, since the book I’m writing is about a king of Sicily in the 13th century who was a great falconer. I can distinguish now between long winged and short winged hawks, ones with straight tails and fan tails, and I know which are the best hunters. Yet with my overburdened imagination the sightings seem to suggest a lighting attack by some evil creature with long claws, coming from nowhere to snatch my daughter.

I try to push such fantasies away. Next week I’m invited to go canoeing on the Thornton River. My friend assures me that there is more than six feet distance between the paddlers in the bow and the stern. The paddle, I hope, will put my mind at ease.

The author in his study at the cabin

James Reston, Jr. is an author of 18 books. His novel about 9/11, The Nineteenth Hijacker, will be published next spring.

Jim, there are beautiful and powerful descriptions of so many things in this — too much to do justice to in one brief comment. Among many other things, you have brought to mind my own upbringing in the region of Fiery Run, among the birds and the trees, in that wonderful corner of Fauquier County which I will always think of as home. Looking forward to reading what you have been working on out there, and thinking of you and your family and hoping you all are well.

Thank you, Jim, for this delicate rendition of your history at Fiery Run. I find the writing sublime in the way it touches down into the arc of your history at the place, each vignette painted into visuals.

We recently moved to the area that is the focal point of this essay, I must say we absolutely love it here. It is such an escape, as the author potrays so well here. It reminds me of my own childhood and time with my grandparents who are no longer with us. Prior to stumbling upon this essay, I was nieve to much of the history, as well as the author, James Reston, Jr. I look forward to tracking down some of his novels and gaining new insight into the past.