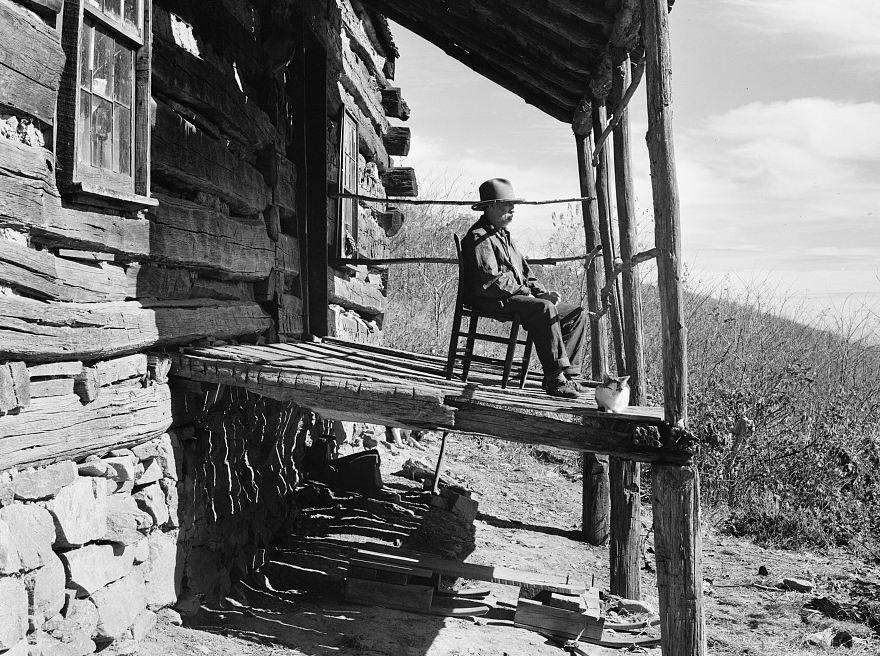

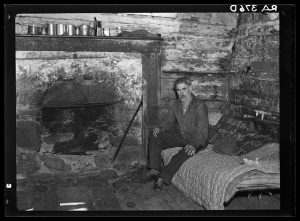

Images by Arthur Rothstein, circa 1935, Library of Congress

House in Corbin Hollow

Introduction by Linda Roberts

Mountain Hike Leads to Writer’s First Novel

Go Down the Mountain brings to light the residents’ plight during the creation of Shenandoah National Park

A decade ago, Meredith Battle came across the remains of an old foundation and chimney while hiking in the Shenandoah National Park in the Blue Ridge Mountains. At the time she had no idea that her discovery would lead to the creation of her first novel, Go Down the Mountain.

Sitting in the dining room of her family’s historic home in the quaint village of Waterford in western Loudoun County, Battle reflected over the ensuing years. She outlined the turn of events that set her on a winding pathway toward publishing a fictional novel based on an actual event now chronicled as part of history.

Battle often thought back to the old ruins she stumbled upon on her hike and wondered to herself who had lived there and why would they leave such a beautiful place. She eventually decided to take action on her thoughts and began researching the Shenandoah National Park. At the time she was living in California where her husband’s job had landed the family and her investigations provided a welcome tie back to her roots in Virginia.

What Battle discovered as she dug into the Park’s origins was alarming to her and set in motion a strong desire to express her findings in writing. She chose a novel format and created a cast of fictional characters, including the intrepid heroine, aptly named Busy Bee, as the vehicle. Told through the eyes of Busy Bee, the plot twists and turns, weaving in stories and challenges of the mountain people who once lived in what is now the Shenandoah National Park.

“I always loved to write and wanted to be a writer,” said Battle, who grew up following her talent and later found it a natural part of her career in public affairs. Her research provided the outlet to try her hand at fiction and gave her an opportunity to share what she found was a compelling story. Go down the Mountain is a tribute to her father, who was “my sounding board and cheerleader” for the novel.

Using a variety of sources in her research, Battle learned that some 500 families were displaced when Virginia began amassing tracts of land that would eventually be gifted to the federal government to create the Shenandoah National Park. The families were evicted to resettlement areas after being paid small sums for their property if they moved willingly. Those who protested were forcibly evicted and given no compensation. There was no negotiation, Battle said.

The government misled the homesteaders, Battle said, noting that while they were sometimes told they could eventually return that was never the intent. Homes and barns were burned to further bring an abrupt ending to their lives in the mountains. Meanwhile, the settlers were not allowed to return to harvest any crops that they had planted.

Battle’s months of research “were like uncovering the answers to a mystery, since I didn’t know the story,” she said. “I could virtually go to Virginia from California,” she added, noting that her background information was gathered using the Internet, including listening to interviews housed in a special collections library at James Madison University in Harrisonburg that was available online. The Library of Congress also yielded important information, including that about a real life photographer, upon which she shaped one of her characters, Miles, who was hired by the government to photograph the homesteaders.

Completing her novel, Battle thought it would have only limited appeal, perhaps regional. She has been surprised at its widespread and growing popularity since its publication in April. To date, Go Down the Mountain has been on several Amazon bestseller lists and its appeal has been national in scope. Battle’s Facebook page has fanned the novel’s outreach and appeal, linking thousands of interested people together.

“I have gotten such positive feedback,” she said, adding that the descendants of the displaced people have loved the book. “It’s been such a rewarding process for me,” said Battle, who felt she has been a link in bringing together families whose ancestors once lived in Virginia’s mountains. “They are so appreciative of the book and thankful to me that I didn’t write about their grandparents as uneducated poor hillbillies as mountain people are so frequently portrayed.”

Battle has enjoyed giving several talks and book signings, such as a presentation at James Madison University and attending an annual homecoming event staged by descendants of the displaced families of the Shenandoah National Park. Meanwhile, she has another book in mind and looks forward to the winter months to get started.

“I’m an introvert,” she said, adding that she likes nothing better than to be at home writing. “I get my best creative thoughts going while I am walking the dog,” she added with a laugh.

Enjoying life with her son, Lucian, and husband, Joe, in the eighteenth-century village of Waterford, Battle takes an active role in community affairs. Her next novel will be set in a fictional small town, which like Waterford, is struggling to preserve its history while the area all around it is rapidly growing. Her characters are already mapped out and Battle smiled when she said her challenge is not to make them too much like Waterford’s real residents.

“Writing is a labor of love,” she said, adding “I hope I will enjoy the next book as much as I have Go Down the Mountain.”

The History: The Creation of Shenandoah National Park

Stretching from Front Royal at its northern end almost to Waynesboro at the south, the Shenandoah National Park is bordered by the Shenandoah River to the west and the Piedmont’s rolling foothills of the Blue Ridge Mountains to the east. Its 200,000 acres are home to wildlife, beautiful waterfalls, amazing vistas and overlooks, campgrounds and lodges, and quiet, wooded trails. The Skyline Drive bisects the Park and provides visitors a 105-mile route running its length.

Visitors hiking the many pathways that crisscross the Park may also find stone foundations, chimneys, cemeteries, and apple trees just as Battle did on her hike. These present-day reminders help to form the stories of people who were displaced when legislation was created to create the Park.

In 1926, Congress authorized legislation that would eventually result in the Park’s formal establishment in 1935. It was dedicated by President Franklin Roosevelt in 1936. During this same time, the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) was at work in the Park, providing training and jobs to thousands of Virginians.

Because legislation stipulated that no federal funding could be used to purchase land for the Park, the Commonwealth of Virginia used state funds to buy the land, which was eventually gifted to the federal government. When the mountain residents refused the sums offered for their property, they were evicted by the process of eminent domain. Homes and outbuildings were often burned to ensure the displaced residents could not return. Considered then a humanitarian act, the eugenics movement — a movement to “improve the human race” by selective sterilization of people with “undesirable” traits — was reaching its peak about the same time, and in Virginia it affected thousands of residents including some of the mountain people.

More than 3,000 individual tracts of land were eventually assembled to create the Shenandoah National Park and some 500 families from eight Virginia counties were displaced. Books and papers outline the stories of the displaced residents and studies have been underway for years to uncover and preserve a way of life gone forever. To keep alive the history of the mountain people, descendants of the displaced formed a group called Children of the Shenandoah to share stories and maintain family connections.

Today, some 1.2 million visitors come to the Shenandoah National Park each year to enjoy its many offerings. Many will come across old foundations of homes once belonging to displaced residents and their interest may be piqued, as was Meredith Battle’s, to learn more about the people who once made the park their home.

Excerpt:

Go Down the Mountain by Meredith Battle

In all those years between the first Livingstons and me, only the chestnut trees changed. They got done in by blight when I was an ankle biter — the same year cousin Samuel went moonlight coon hunting dead drunk and stumbled his fool self to a broken neck at the bottom of Thompson’s Gorge. Put your nose up close to their trunks and you might have thought an angry bear had its way with them. They were all torn up with gashes where the blight’s sores split their bark. But even dead those trees stayed standing. I used to pretend they tracked who came and went from the Hollow, good as any hired guards. Turns out they couldn’t keep the bad away.

In all those years between the first Livingstons and me, only the chestnut trees changed. They got done in by blight when I was an ankle biter — the same year cousin Samuel went moonlight coon hunting dead drunk and stumbled his fool self to a broken neck at the bottom of Thompson’s Gorge. Put your nose up close to their trunks and you might have thought an angry bear had its way with them. They were all torn up with gashes where the blight’s sores split their bark. But even dead those trees stayed standing. I used to pretend they tracked who came and went from the Hollow, good as any hired guards. Turns out they couldn’t keep the bad away.

I passed by those trees plenty but, when I first laid eyes on Miles Everheart, I still hadn’t gone farther than to Luray with my Daddy and to Richmond to see Mama’s family. I reckon that was why I was so eaten up with need to be with Miles. He wasn’t much older than me, and there he was about to cross the country and see places I could only visit in books. Being with him felt like maybe I could claim a little part of his adventure for myself.

Now’s as good a time as any to tell you I have two beaus in this story. There was Miles. I’m just about to spell out how I fell for him fast as a rock tossed off a ledge. The second one, Torch, started out as a boy who grew up with me on the mountain. We were so much alike we could have been that pair of Siamese twins from England I read about in the paper once, except instead of being attached by an ass cheek, we shared one mind. I’ll get to Torch in a spell.

Miles was a government photographer come from Washington to take pictures of the Hollow for an office called the Resettlement Administration. His boss told him his photographs would make the case for helping poor people down on their luck. He believed it and so did I when he told me. It’s easy to look back now and see us as fools. I’ll remind you that, until a few years ago, we’d never heard of the government stealing land away from anybody — at least not white folks.

Miles spent a month in the Hollow before he got his next assignment. Those weeks shine in my memory. I had a fondness for him that was fierce at its beginning. The first day we met at MacArthur’s Store he offered me five dollars to show him the Hollow. That was a whole hell of a lot of money to me so I agreed even though common sense told me leading a city man around was going to be more than five dollars’ worth of trouble. I made him pay me half up front and came up with a plan to ditch him. I took him straight up the mountain on the steepest, rockiest trail I knew. Hard as I tried to shake him, Miles stayed with me the whole way to the top. I’m still stumped about how he managed it. He slipped and slid so much in his city shoes you’d have thought he was a newborn fawn strapped into a pair of ice skates. He never complained once though, not even when he fell on his ass in the briar patch I went out of my way to take him through.

I agreed to meet him at MacArthur’s again the next day. I noticed right away he’d gone and bought himself some sensible boots and jeans that would stand up to a few briar pricks. I also noticed he was handsome in a fine-boned, citified way. He looked painted with one color, a sort of hazel all over, except for his lips which were a bubblegum pink and seemed an advertisement to kiss him, which I did later that day. It wasn’t long before he was nothing but hungry hands and eyes whenever it was just us two. He had a nervous air about him that got soothed when he was alone with me. I liked having such an effect.

We laid together in the orchard the day he left the Hollow. He took my picture and sent it to me months later. In it, my skin was the silver of mercury. My black hair twisted wildly as Medusa’s snakes. My gray eyes teased his camera. He said he carried a print of that same photo in his bag. I liked to think of him looking at me, even from far away.

I’m glad I haven’t forgotten that last day on the mountain with him. Even the grass remembered us for a while, pressed flat by two bodies, bruised by our romp before he left to go back to the world. Maybe I shouldn’t mention anything to you about me being with a man who wasn’t my husband. A proper mother, like the ones here in the city, wouldn’t. God knows there’s never been much proper about me. I was educated. Mama was the Hollow school teacher and she saw to that. But I’ve always used words I shouldn’t, like goddamn and bastard, and I let my heart get so hot it boils over. Mothers and girls never had much use for me, but boys and men always seemed eager to see me happy.

After the snakes killed Daddy, there were plenty of boys, men even, who came around with apple butter jars or scratched and bleeding arms full of the best huckleberries from the thistly patch up on goat’s trail. If you want to know, I kissed a few of them. But Miles was the first man I ever laid with. I’m not ashamed to say the love I had with him, wrestled to its end in the cool shade of the apple trees, was sweeter to me than the best whiskey. Yes, your mama has tasted whiskey too. I hope you won’t take it too hard if, in the course of reading these pages, you find out I’m not as ladylike as you might have hoped.

His boss at the Resettlement Administration aimed to make Miles a happy carpetbagger — Alabama and Arkansas, then the Midwest and on to California (where I’d heard the land was so rich, a strawberry seed spit into the dirt would bloom into a plant in a week’s time). It satisfied him to know his pictures would do good, that Uncle Sam would use them to make the case to the American taxpayers for helping folks down on their luck. I got my first letter from him when he settled in down south. When I looked up from those hushed pages, I was wading through a sea of white Alabama cotton alongside Negro pickers, black as wet fieldstone, glory-to-God hymns rising from their work-wasted bodies like steam. The wicked Dixie sun prickled our skin, stung our eyes with sweat. Prickly cotton plants tore at my clothes, jealous lovers, greedy for another touch. I was sweet on Miles before he left. Soon as I read that letter, I was sure I’d fallen whole hog in love.

Post Office at Nethers

When it came time for me to write back, I was afraid my letter would be the end of it. Mama had us write plenty of practice letters at school, but my letter to Miles was only the second one I’d ever mailed. The first was for a school project. Mama found us a group of pen pals at a school in Washington, D.C. and I wrote to mine about the dead, bloated deer that exploded all over Daddy when he hit it with a stick because he was too drunk to think better of it. Everybody in class got a return letter but me, so I’d come to believe I wasn’t cut out for correspondence.

I steered clear of dead, rotting things and wrote about my feelings for Miles instead. Mama always said I put too much stock in feelings. She called it a sickness and said I ought to hope for a cure, but back then I would have picked death over living without someone who could make the letters light up when they said my name. Miles did that in the beginning. So do you, sweet girl, every time you say mama.

My Mama was healthy as a horse on spring grass, free from the kind of sentiment that ailed me. I suspected it was because I’d been such a calamity as a daughter. She had to harden her heart to weather the disappointment. I used to try to change myself to please her. I only succeeded once in a while and, when I did, her goodwill flitted away again quick as a hummingbird.

There was some ugly business between Mama and me the day I got that first letter from Miles. I remember because I was all goo-goo eyed after I read my name written in his hand and not at all ready for what came next. A state man called Rowler was the cause of it. He came by our place and said the state had given our land to Uncle Sam for a park. We were to be out in five months or be considered at odds with the law.

Mama told him we’d sell. Our land was worth fifteen dollars an acre, she said. She made a big speech about how we wouldn’t take any less for it. While she talked, Rowler looked me up and down and licked his lips like I was a slice of scrapple fresh from the frying pan.

He was the kind of husky white man who had a layer of pasty fat on him from sitting on his ass in a desk chair, his cheeks flushed pink from sneaking sips of whiskey. His brown mustache twitched even when he wasn’t talking, until I thought it might jump off his face and scurry into a hole in the floorboards.

He told Mama we wouldn’t get squat since Daddy’s people never filed papers with the county courthouse. I figured as much. Daddy always said the Livingstons didn’t need papers when a handshake and a man’s word would do. Seems like we didn’t need a deed when the whole goddamned Hollow was named for us.

Mama was fit to be tied. Rowler grinned a pleased-with-himself grin. Then he tried to make a deal with Mama that would have made the devil flinch.

John Nicholson peeling apples

“Your girl looks like she sure could keep a man warm at night,” he said. “If she had a notion to show me some kindness, I’d see to it you get one of the houses the government’s built for your people, down on Resettlement Road.” I took a sideways glance at Mama and saw she looked confused. Rowler must have seen it too because he spoke plain as he could and still lay claim to a shred of decency. “It’ll take some time with your daughter to bring out my generous nature. Without it, you’re on your own.”

Mama went mute. He told her to take some time to think it over. He’d be back.

Me and Mama had a whopping row after he left. I was mad as hell at her for not telling him off soon as he opened his mouth about me. She said didn’t I know what shock was and how could she be expected to have her wits about her after what he’d asked. But when I pressed her to swear she’d set him straight the next time, she wouldn’t do it. She just kept on about how we were in a heap of trouble if we got kicked off our land with no money to show for it.

“Just flirt with him a little until we get one of those houses,” she said. “Let him think he’s got a chance.”

I lost my temper. “He wants more than that,” I said. “Are you planning to whore out your own daughter?” She gave me two good smacks across the face and that was the end of it.

Mama and I were always oil and water. Rowler shaking us up did more harm than good. He was after me to lay with him and all Mama could do was chew it over. I wasn’t a nervous girl, but I was near about having kittens over it. I had to sneak a sip or two of white mule (that’s what us mountain folks called whiskey) to get to sleep that night.

BAD TIMES COMING

[At the Corn Shucking at Ruth and Peter’s]

By the time I got to the barn, a few of the men had taken up the fiddle and the mouth harp and two red-ear cheaters had downed their first drinks. We had a corn shucking tradition that the man who unwrapped a red ear got a swig of the farmer’s whiskey. Ruth’s husband Peter bought bonded liquor all the way from Kentucky. It tasted better than anything we made in mountain stills. You’ve never seen so many red ears of corn in your life. Peter was a good spirit so he never did call them on it.

The corn got shucked in spite of all the drinking. Then people pushed the chairs up against the barn walls and paired off for dancing in the middle. I didn’t dare dance in front of Mama. Something about the heat still in her eyes told me it’d be best not to. I was careful not to bump the barn door open wider when I eased through the crack in it, so she didn’t see me leave.

I found three of the men outside passing a quart jug of white mule. They were singing ballads and carrying on to an oil lantern that had grown so tired of their nonsense it could only turn out a weak glimmer. Torch was there with Red Monroe and Ruth’s husband Peter.

Torch and Red made a harebrained pair when they were together, I can tell you. Torch started out like a brother to me, except when he was around Red sometimes I didn’t care to claim him. I’ll get to him a few pages from now. His troubles take some time to tell, so I can’t fit them in here.

Red was a good ten years older than Torch. I guess that made him somewhere around thirty. Don’t be confused into thinking Red was any more mature for his age. He had himself a devilish nature that got him into plenty of trouble. When he was fifteen, he fell out of a scrawny pine his horny self climbed to get a look at a couple of girls splashing around Miller’s swimming hole in the altogether. He cracked his left hip bone and he had an old man’s limp because of it.

Adam Nicholson

You may have guessed from his name that Red had hair the color of fire. I’d heard it said redheads couldn’t be trusted. Daddy told me that was superstition folks carried in their suitcases from whatever old country they were born in. Daddy didn’t go in much for superstition. I didn’t usually either, but Red did a damned fine job proving this one to be true. When his mama died, he cut off her long silver hair and sold it to a doll maker in Luray for a dollar before his family could get her in the ground. He knocked up a girl in Sperryville after he made sure to tell her he was from a town called Syria so her Daddy wouldn’t be able to find him.

Red surprised everybody when he managed to talk a godly girl from Corbin Hollow named Sarah into marrying him. She had her work cut out for her with him, I’ll tell you. The only thing Red liked to work at was sex. He knocked Sarah up five times in as many years. Rumor had it after baby number five she locked him out of her kitty except for his birthday and Christmas. I can’t imagine Red going without so, if it was true, I guess he had his way with sheep at night.

When I found them outside at the shucking party, Torch and Red were fighting for a turn to prove who was man enough to muscle what looked to be a half-ton rock off the ground. Torch pushed his body into the rock and moaned with his eyes squeezed shut. He looked like a blind chipmunk trying to screw a pumpkin and I told him so. Torch said if he was screwing he’d pick a girl not a pumpkin and he’d be good at it. He offered me a chance to verify his skills first hand, but I told him to take a flying leap.

Red offered me a cigarette, which I was fool enough to take. He handed me a book of nudie matches with three naked girls painted on the paper folder and across each comb inside, so that every match you tore out had tits or ass on it. Then he said, “Go ‘head, grab yourself a piece of ass, Bee,” which cracked Torch up.

I pulled loose a match with a big pair of knockers on it and held it out to Red. “Aww Red, don’t you want this one? From what I’ve heard, these are the only hooters you’ll get your hands on ‘til Christmas.”

Torch and Peter both yucked it up at my joke. Red did not. His face turned ruddy as his hair. He changed the subject quick as he could. “Peter,” he said, “play us that song Bee’s partial to. That ought to shut her up for a while.”

Peter loved to sing, so it didn’t take any more encouragement then Red asking. Peter had a voice that would shake the ground much as any storm’s thunder. I didn’t mind since he was singing my favorite love story. I know you want to correct me and tell me to call it a song not a story, but if you let it sit with you a minute you’ve got to agree songs are just stories set to music, like the one Peter sang about two lovers who died young and got buried toe to toe:

They buried Willie in the old churchyard,

And Barbara there anigh him,

And out of his grave grew a red, red rose, And out of hers, a briar.

They grew and grew in the old churchyard,

Till they could grow no higher,

They lapped and tied in a true love’s knot.

The rose ran round the briar.

When Peter finished it was quiet for a while, then the real talk started. I’ll try my best to lay it out for you here, since the men were full of news about the Hollow getting turned into a park so that city folks could come weekends and crunch pine needles under their feet.

Red, whose daddy Wilbur was so long in the tooth even his skin was gray, said Wilbur’d been threatening to die ever since they got the letter that said to clear out. Red told his daddy not to worry, because the government was going to buy everybody’s land and they were giving away farms down mountain to boot. I wasn’t sure that was much comfort to Old Wilbur. He’d been walking cockeyed up our rocky hillsides for so long I suspected his body might not work right on level land.

Fennel Corbin

Torch accused Red of being fool enough to buy a bottle of sugar water from a traveling salesman if the swindler said it would fix his tongue. Red ate a lye soap cake when he was a boy and it burned the inside of his mouth so badly his r’s sounded more like w’s. Torch’s remark wasn’t a kindly one, but meanness was the way Torch and Red related. Anyway, everybody was fit to be tied about the government’s letter, so folks were more hard edges than usual. When Torch talked about being forced to leave, his words came out in a soft growl like a hurt animal warning you off. Made me want to touch him to see if he’d take a bite out of me.

Torch went on to calculate that if the government handed out free farms to all five hundred of us left across four hollows it would go bankrupt. Torch got all kinds of smart ideas from the folks who stopped in at his daddy’s general store. It had a gas pump out front so they came from all over. He picked up a more refined way of talking there too, so sometimes he sounded more like an out-of-towner than a mountain boy. I was sure the store was where he picked up his bankruptcy notion.

Torch’s remark started a heated debate about whether he was calling Red a liar. At the end of it, Torch called Red a backwoods brain and said we’d all be lucky to get pennies on the dollar for what our land was worth. Apparently, he’d heard Arnie Ross, from over in Corbin Hollow, talking down at the store. Arnie didn’t file papers at the county courthouse when he bought his land, so the government was calling him a squatter and saying they wouldn’t pay him a red cent. I wouldn’t have believed it if it wasn’t happening to Mama and me. Torch said they weren’t giving away farms either. “We’ve got to pay. My question is, if we don’t get a fair price for our land here, how in the sam hill do they think we can afford to buy government land?”

Right about that time Red’s face started to look like a hog’s on killing day (I don’t know how those pigs know it, but they do. You look into their nervous little eyes and tell me otherwise). I remember exactly what he said, because he sort of croaked it. “You saying we ain’t gonna get nothing?”

Peter didn’t like to see anybody in a tough spot (you’d never see hide nor hair of him come slaughter time), so he spoke up. He was rawboned, with a heart so big it was a miracle his thin frame could hold it. He told Red not to worry, that the government just wanted us out while they laid the park roads. “They gonna let us come on back,” he said. “It’s just for a spell, Red. Just for a spell.” All three men went mute after that. The festive mood they’d shared before had gone right out of them.

Peter’s family landed in the Hollow smack in the middle of the 1800s and built a two-story frame house three windows wide, with four rooms and a stone chimney — pretty fancy for those parts. They farmed the land and made an honest living, if not always a goodsized one. Every one of Peter’s kin who kicked the bucket since then was buried on that land. When Ruth’s mama and daddy passed after she married Peter, she buried them there too.

There were others who’d gone down the mountain. Indians lived there and left. They killed deer with stone-tipped arrows and stretched their hides across boulders to dry in the sun. There were Negroes there once too, slaves to the families that could afford them. As soon as Mr. Lincoln won the war between the states, they went away. Seems like all those folks were going toward something. Food. Freedom. There wasn’t anything waiting for us. Our houses and our dead were on Ragged Mountain.

“Go Down the Mountain” can be purchased at fine booksellers and online at amazon.com

Leave a Reply