The Art of Sam Robinson

“Curve of Stones”, 18 x 24, Oil

Story by Kaitlin Hill, Images provided by Sam Robinson Fine Art

Picasso once said, “Every now and then one paints a picture that seems to have opened a door and serves as a stepping stone to other things.” More than an open door and stepping stone, Sam Robinson offers his audience full immersion into the equine world of the Piedmont region. From fox hunting to spring races, Robinson captures equestrian scenes with both accurate detail and poetic expression. His masterful pieces are the culmination of his Eastern roots and Western training, an obvious fascination with his subjects, and a desire to push the limits of his craft and see where he ends up.

Robinson is the official artist for the Montpelier Races, as well as National Steeplechase Association events in Middleburg and The Plains. By Richard Clay Photo

“I don’t recall what initially attracted me to art. Drawing was just something I did from an early age,” Robinson shares of his artistic roots. “I just kept drawing and I would get positive feedback. So, I knew early on that I had a talent for it and received constant encouragement.”

Robinson, the son of medical missionaries, grew up in South Korea’ where he received his earliest artistic training. “Since I was in Korea, the first formal lessons available were in Asian ink brush painting. That is what I started with and it is a great thing because I’ve always had a really strong interest in what you can do with a brush,” Robinson remembers.

Back in the states, Robinson continued his education at the Maryland Institute College of Art (MICA) where he focused on the Western approach to painting and refined his skills with life drawing and figurative sculpture classes.

Though his father offered to help and encouraged Robinson to get a master’s degree, the young artist was eager to “get going.”

“I knew I didn’t want to be a teacher. And the only thing a master’s degree offered, from my perspective, was a document that would qualify me for a college level teaching job.” He adds, “I knew instinctively that’s not what I wanted to do. Learning painting is a very pragmatic practice and it’s very much about making progress on your own.”

For Robinson, developing his own style meant identifying as a Western painter but using those early Eastern roots. He notes, “The Impressionist movement was strongly influenced by, in particular, Japanese woodblock prints. You can cite some French painters or American painters that look to the prints for simplicity of design, a certain kind of flatness, and an appreciation for silhouette. I am a living example of that, really trying to get the appearance of something by its gesture and silhouette. Each brush stroke is put down with a lot of thought to get the most expression out of it.”

Robinson blends the importance of brush stroke with his mastery of light. He adds, “While all those things are still completely true in my work, I’ve gravitated more towards the European tradition, which is understanding how light appears to be falling across, say, a field of horses.”

Not a rider himself, his interest in equestrian scenes comes from a family connection to the area and a love of both landscape and portrait work. Robinson says, “It is a background and tradition that was connected to me that I really hadn’t paid much attention to.” Robinson and his family live in Green Spring Valley, Md., just a short drive from a lot of equestrian action.

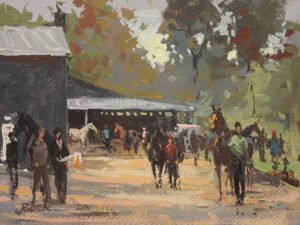

“Bedford Barn”, 6 x 8, Gouache

“There is The Green Spring Valley Hunt and the kennels, and The Hunt Cup, the top race in the Maryland Timber Racing Triple Crown. They are all right there. My mother’s cousin, Ned Murray, would always invite us to come out to The Hunt Cup to watch the races. It was really a family affair,” he recalls.

His family’s familiarity with the events provided Robinson with an awareness of the equestrian world, but it was a commission that cemented his focus on the activity. He says, “The direct involvement with the subject was a result of my interest in portrait painting.” Robinson was hired to paint George Mahoney, a master of foxhounds with The Green Spring Valley Hounds. He remembers, “I thought, ‘Well, I could just do the usual thing and stick him in a chair, but I might as well go see what this fox hunting thing is about.”

Robinson was captivated. “I found this fantastic subject that, I think, is inexhaustible and it combines beautiful landscape, the individual people who are fascinating, beautiful animals, the thoroughbreds, and the hounds are equally interesting.” He expands, “I was interested in painting the landscape and portraiture, and those came together. Those are the two threads for what is broadly termed ‘sporting art,’ in this case particularly equestrian. And I found this new enthusiasm for the subject that combined it all. There was just so much there, and I just jumped in and painted several scenes.”

As in his childhood, Robinson was spurred on by positive feedback. He recalls, “Mr. Mahoney was very encouraging, and he told me to go show them to this travelling exhibition, organized by the Crossgate Gallery, that marked the centennial year of the Masters of Foxhounds Association of North America. They were very enthused with the work and took three paintings I had just done and put them on this national tour.” He finishes, “That was in 2007, and I’ve just continued from there.”

Over time, Robinson developed a system to tackle the challenges of capturing an ever-changing scene.

“Step Lively”, 24 x 30, Oil

Robinson laughs, “When I first started this, I didn’t know what I was looking at. I didn’t know what was going on. I can paint the landscape, but then all the people and the horses moving around was just completely overwhelming.

“So I realized that in order to paint a horse from life, I pretty much had to memorize the horse. I put myself through a self-study program, which included doing some sculptures. Because when you make something with your hands, it helps you understand the shapes more thoroughly and for some reason you retain it in your memory.”

With the anatomy of a horse committed to memory, Robinson was off to the races, literally.

“Working from life adds a lot of vitality to the work that I do. I usually set up by the paddock. It’s a good place to be because there is constant turnover and yet, in a way, it’s the same thing happening over and over. And I generally take a medium called gouache. It’s a watercolor basically, but it’s an opaque watercolor that looks a lot like oil painting.” He elaborates, “I generate a whole bunch of sketches in a day and use my camera to record information for more ambitious projects or oil paintings that are then created in the studio.”

Having covered many of the Maryland events, he expanded into Virginia and his reputation grew among equestrian bigwigs in the Piedmont region. In 2018, Robinson was named the official artist for the Montpelier Races. “They have continued the tradition that other races used to do, where they have an annual poster artist. They pick an artist they want to work with, and they recruit you. You paint the Montpelier Race, and they auction off the original piece. You go to the dinner and you’re included in the festivities. It was very fun,” he says.

Robinson is also the official artist of The National Steeplechase Association with events in Middleburg and The Plains. He notes, “One of my most consistent fun racing experiences is Glenwood Park in Middleburg. They run the spring races and the fall races. I almost always get down for the fall races, which are uniformly fantastic. Another one I love is the Piedmont Hunt club. They have their point-to-point races and that’s a really nice race.” He finishes, “Plus, I love anything that has the Blue Ridge in the background. It adds this gorgeous, lovely kind of ultramarine blue note back in the distance that is nice to have.”

“Masked Rider”, 11 x 14, Oil

More than his talent and well-deserved titles, the equestrian community is what keeps Robinson coming back. Of the experience he shares, “I really have a relationship with the audience, and I think that is kind of unique. It is a huge welcoming community of people in the horse world. They have really embraced what I do, and they seem to genuinely appreciate the fact that I make the effort to get it right.” He concludes, “To me, that is the rewarding part of it. They’re very supportive.”

With many 2020 events cancelled due to the Covid-19 pandemic, Robinson used the time to explore his artistic expressions on a deeper level.

He shares, “The lockdown period has been useful to me. It has allowed me to step back and look at the paintings. To look at what the creative, expressive potential of this piece is, beyond the interest of an audience who loves the sport.

“I think I’ve earned my stripes. Most of the people who know me and know my work from the horse world, they know that I’ve put in my time and done my homework. And that I do it accurately. Now what I would like to do is show you the poetry, step beyond that and look for what I call the universal expressive elements. I think people who are watching my work will see me moving towards the direction of [painting] things that I find compelling and beautiful versus just memorializing that horse that won in that race in that year.”

Admirable though his ambitions may be, Robinson’s audience will argue his art needs no adjusting. His keen eye for interesting scenes, his purposeful brushwork, and mastery of capturing the unique energy of equestrian events result in works of art that are beyond beautiful and unquestionably compelling. With plans to return to the field for the 2021 season, it’s safe to say equestrians can expect more excellence from his easel this year and for years to come.

Leave a Reply