This magical place in Greene County can be found just a short hike off the Skyline Drive.

By Kristie Kendall

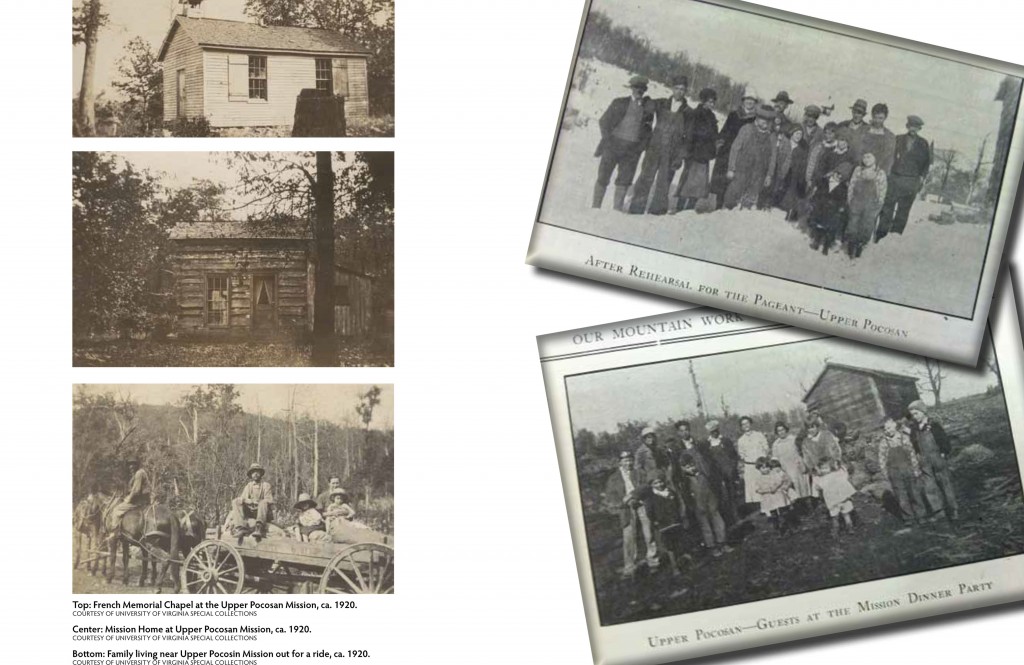

Photos courtesy of University of Virginia Special Collections

Only a mile from Skyline Drive, but deep in the woods of Shenandoah National Park, in Greene County, stands a seemingly curious sight for one to stumble upon while hiking through the forest – stones, piles of stones, and a frame structure nearby. A cemetery stands quietly across the road. Window glass and wrought iron pieces are scattered across the ground.

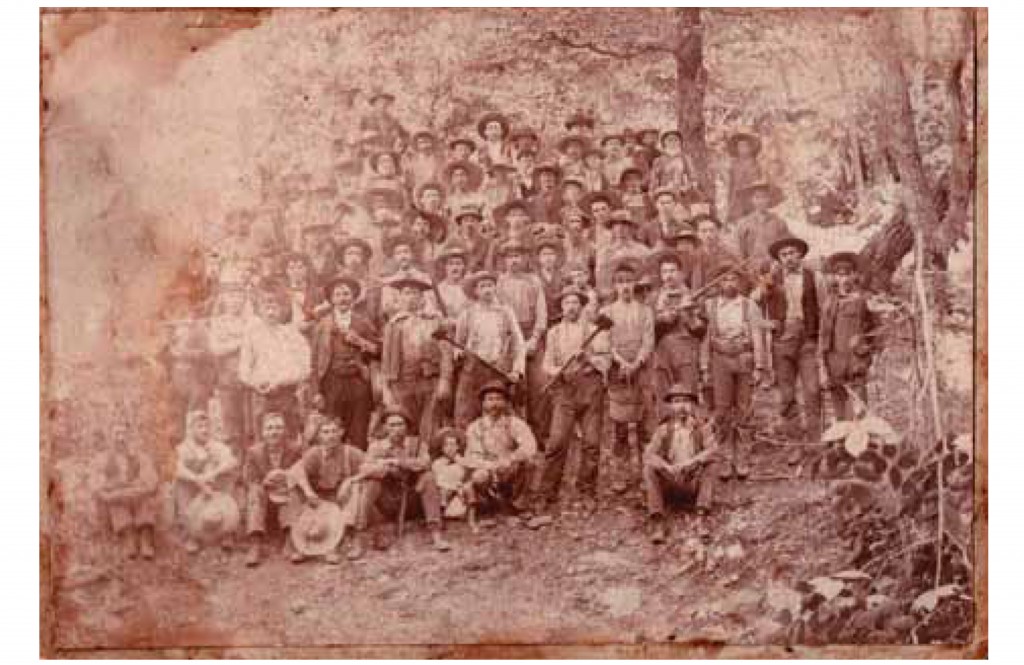

Long before these lands became Shenandoah National Park, they belonged to hundreds of mountaineer families, with claims to the land dating to the late 1700s. By the 1930s, hundreds of home sites were scattered throughout the Blue Ridge Mountains.

Roughly bounded by the mountain which holds its name, the remnants of one of these mountain communities, simply known as “Pocosan,” can still be seen today. Accessed from Skyline Drive at the Milepost (MP) 59.5, the Pocosan Fire Road leading from this parking area was once the main thoroughfare for the Pocosan community. A roughly two-mile round trip hike takes hikers back in time to a little known piece of history. Here’s your annotated trail guide:

MP 0-0.2

Hike south on the yellow-blazed Pocosan Fire Road for about 500 feet and cross over the Appalachian Trail. After passing this famous white-blazed trail, a log cabin known as the ‘Pocosin Cabin,’ will appear after another 500 feet on your right. Constructed by the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) in 1936, the Potomac Appalachian Trail Club now maintains it for overnight use by hikers.

This cabin was actually the second structure to be built on the site. The first cabin was a larger frame structure located just above the trail. Preston Breeden, his mother Clara, grandmother Estelle, and two brothers lived here. Preston’s grandmother and great-grandparents had called the mountains home since the mid-1800s. The 1.5-story house stood on pillars and included a living room, kitchen, and bedrooms. A natural spring, just southwest of the present-day cabin, flowed steadily and served as the family’s water source. Preston and his family, forced to relocate when their land was condemned for the park, watched their house be torn down and later burned.

MP 0.2-0.5

Continue to follow the trail as it heads gradually downhill. Walking along this road in the 1930s, you would have been able to see below the trail to a number of houses standing in Pocosan Hollow. Both sides of Pocosan Road would have been cleared from years of harvesting chestnut and white oak timber. A steam-powered sawmill and stave mill once stood above the Pocosan Cabin and was operated by a number of local families, including Meshack Samuels and Luther Kite.

Using a two-wheeled cart or a “dinky,” they would hoist logs uphill with large chains along laid track. Most of the men in the mountains were employed in the timber harvest, which required weeks of work every spring and fall. Wagon teams would transport hundreds of pounds of bark 30 miles over the mountain to the Shenandoah Valley, twice a week in the spring, and then make the same trip with logs in the fall.

The area above the trail here, known locally as “The Deadening,” was created by cutting away rings of bark to kill an area of trees. The dead trees remained standing, but they grew no leaves, enabling the sun to shine through and plants to grow. Later, the trees would be cut for lumber. The area was ideal for summer pasture. Women would come out of the Pocosan community early in the morning to pick ginger and ginseng, which grew in abundance. They would spend all day gathering the roots, leaving in the evenings to strip it, dry it, and later sell it at Fletcher, the local store.

MP 0.5-1.0

A half-mile down the trail, take a moment to look up at the mountain knoll above you. Luther Kite built a gas station on this knoll not long after Skyline Drive was constructed. The new scenic road passed directly through his property, which straddled both the Greene and Rockingham County sides of the mountain. His gas station included two Esso gas pumps, a home, one finished and one unfinished cottage, a hog pen, and a 60-foot bored well, running 40 gallons of water per minute.

Continue down the trail for another half mile and you will arrive at an intersection with the Pocosan Trail. Make a right here and a few structures will immediately appear on your left. The frame structure you first see and the rock foundation next to it are remnants of the Upper Pocosan Episcopal Mission. Established in 1908 by Archdeacon of the Blue Ridge, Frederick Neve, the mission served the surrounding families as a church and school and was the heart of the Pocosan community.

The frame structure served as the home of the mission workers, and was once a beautiful log and frame cabin. The first church here stood to the left of the mission home and was known as the French Memorial Chapel. It was a large, white frame building with a pulpit and balconies that could seat at least 100 people. Until a larger schoolhouse could be built, the building doubled as both regular school and Sunday school. Once the community outgrew this church building, the Episcopal Church raised money to commission a new church built of local stone. Billy Graves, a local mason, completed the stone church in the early 1930s. It is this second stone church which visitors can see remains of today.

The Pocosan Community

The Samuels family, whose home stood nearby, donated land for the church. Two sisters, Florence and Marion Towles, began operations at the mission and, later, another mission below here. Florence married Arthur Meadows, son of a local mountain farmer and stayed on at the Pocosan Mission for more than 15 years. The Meadows family, with other missionaries and preachers, organized weekly church services held every Sunday. After church services, attendees would often gather for dinner at the Samuels home across the street, or Charlie Taylor’s home further down Pocosan Road. The mission workers also tended to the sick and elderly and traveled to each funeral. They taught school to children of all ages five days a week and organized social events like bingo and Christmas pageants.

Melissa, the matriarch of the Samuels family, would regularly clean the schoolhouse and stone church. She would decorate the area for the holiday season and other celebratory events. The remains of the Samuels family property can still be seen if you walk further down the trail and look opposite the mission. A large “wolf tree” stands very close to where the house was located.

Susan Preston, a missionary who visited the Samuels family in the 1920s, described its interior: “Everything about the place was nice and clean. In the room where we ‘rested’ our hats there was a large rock fireplace. In one corner there was a neat-looking bedstead, over which hung the family umbrella. Then there was the usual family clock, rifle, and banjo. The little kitchen where we had our dinner was also very neat. We took our seats on a bench at the table and ate our dinner of cornbread, cooked onions, butter milk, stewed dried apples, and apple butter.”

The Samuels Family/Pocosan Mission Cemetery still stands to the right of the trail. Across from the mission, look for fieldstones and large depressions in the ground. A path leads through the middle of the cemetery, and graves are on either side; but be sure not to disturb the site. At least three generations of the Samuels family have been buried here, dating back to Lucretia and Meshack Samuels, Sr., who first purchased the land in the early 1830s. Their grandson Cicero Samuels and his family were the last to live on the property.

Unforutunately, the Pocosan community was not to last. By the mid-1920s, the Federal government was eyeing the Blue Ridge Mountains, including the area around Pocosan, for a new national park. Not a single mountain family in Greene County agreed to sell their lands, so the Federal Government was forced to use eminent domain to condemn their property, paying the families with funds raised by Commonwealth of Virginia. Beginning in 1936, the families moved what belongings they were able to carry and left their homes and memories behind, to move into the lands below. After 75 years, most remnants of these former homes are gone, either burned or in ruins from years of neglect and forest regeneration around them.

Mesmerized by Pocosan one night during a month-long stay, missionary Susan Preston tried to put to words the beauty of the area.

“Nothing could be more strangely beautiful than all this, it seemed –and yet, there is the late evening when the sun sheds its last soft rays and then the mountains seem to lose their height and loom more closely together, until they look like great waves of the ocean flowing close beneath the sky. Then, as night draws nigh, through the rising fog in the valley comes the road of the mountain stream, the tinkling of cow bells, and now and then a loud “whoop” from a mountaineer. One by one the stars appear, and one by one the whippoorwills begin their weird songs.”

The beauty of Pocosan can still be seen today following this short hike from Skyline Drive, but Park goers rarely visit the area. It is lush with greenery in the summer and bright and quiet in the winter. If you listen closely, you may even here some of those same whippoorwills songs carried in the breeze.

About the Author:

Kristie Kendall holds a bachelor’s degree from James Madison University in History and a Master’s Degree in Historic Preservation from the University of Maryland. She is a native Virginian and works for the Piedmont Environmental Council, where she focuses on land conservation and historic preservation issues.

Leave a Reply