A story of two cousins, one wild dream, and millions of oysters.

By Eric Wallace, Photography courtesy of Rappahannock Oyster Company

Nearly 20 years ago, a pair of cousins with ties to the tiny Rappahannock River community of Topping made a decision that would spark a local-foods revolution and, eventually, transform the East Coast culinary scene. The year was 2001, and Travis Croxton and Ryan Croxton were sharing pints at a Richmond restaurant, slurping oysters from the half-shell—specifically, those imported from the Gulf of Mexico. Saddened by the import, they began to ruminate on the demise of the Chesapeake Bay oyster.

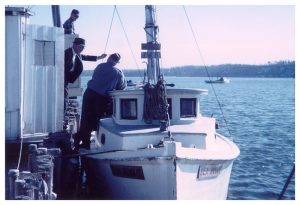

Rappahannock Oyster Company farmers head out at sunrise every day in the Carolina Skiff to harvest oysters for market.

Once upon a time, Bay oyster bars had been so abundant that European explorers were forced to steer around them. Jamestown’s infamous John Smith described the underwater piles as hazardous nautical encumbrances. Eventually, a thriving oyster trade developed. In 1887, at peak harvest, a whopping 24 million bushels—that is, nearly half the oysters consumed in the world—were sourced from the Bay. However, by the time of Travis and Ryan’s reflections, 150 years of unchecked pollution and unsustainable harvesting practices had nearly wiped the population off the map. The decline had rendered their great-grandfather’s century-old oyster business defunct.

Considering the tattered legacy of the family enterprise and the region’s oyster culture in general, the cousins figured it was time for a change. “We decided to revive the Rappahannock Oyster Company, which had unofficially been founded in 1899 and gone out of business in 1991,” says 41-year-old Travis. “At the time, the Chesapeake Bay had just recorded its lowest oyster harvest in history, and the industry looked to be heading for a total collapse. So, for us, the mission seemed pretty clear: We wanted to resurrect the native Bay oyster and put it back on the map.”

Revival

Left: Cousins Ryan and Travis Croxton revitalized the oyster population and resurrected a century-old family business Right: Farm manger Eli Nichols harvesting oysters on the Rappahannock

Consulting with their fathers, the two discovered the family’s century-old lease with the state to farm oysters on 200 acres of Rappahannock river-bottom was about to expire. They promptly assumed the lease. While many thought the cousins had gone insane, the Croxtons refused to be dissuaded. “You have to remember that, in those days, there was talk of moratoriums, even threats to place the Bay oyster on the endangered species list,” Travis says. “In fact, most of the industry had abandoned hope for the native oyster altogether, and was lobbying to introduce a Chinese oyster to take its place.”

Citing the oyster’s critical role in the Bay ecosystem, the Croxtons felt a moral imperative to revive the bivalve. “Initially, we got into this as a means of connecting with our heritage,” Ryan says. “But as we looked at how to make it work, we realized this little animal was, as Muir said, ‘hitched to everything.’ ” Acting as a filter for excess nutrients—namely nitrogen and phosphorus—a thriving oyster population would play a key role in cleaning up the pollution-ravaged Bay. “To hell with bananas,” jokes Travis, “[the oyster] is nature’s most perfect food—fit for our nourishment and the service of our environment.”

Working with a small contingent of local, retired “oyster gardeners,” the cousins decided to implement an experimental cultivation method called “off-bottom aquaculture.”

“Basically, this meant caging the animals and floating them on the surface, where they’re off the muddy seafloor and closer to better food and oxygen,” Travis says. In March of 2002, they seeded 3,000 oysters off a dock in Ware’s Wharf. “That made us the [Rappahannock Oyster Company’s] fourth-generation of oystermen,” Ryan says. “And while we had no intentions of quitting our day-jobs, we took a lot pride in that fact.”

Left: Home base, the Rappahannock Oyster Company oyster shed and dock in Topping, right across from Merroir Center: After employing an experimental cultivation method called “off bottom aquaculture” for two years, the cousins felt their oysters were ready to be introduced to the world in the spring of 2004 Right: Farm manager Alex Pratt tasting a raw oyster fresh from the river

The decision to use the off-bottom method proved to have a slew of benefits. According to a 2016 study conducted by biologists at Texas A&M University, the method offers several advantages over traditional production methods: faster growth, increased survival, control of fouling (e.g. barnacles, overset oysters, mud worms), improved shell shape and appearance, and increased product consistency. All of these results ultimately led to a product that was healthier, superior tasting, and better-looking than its wild-dredged counterparts.

But for that, the cousins had to wait.

Left: Rappahannock Oyster Co. farm team Right: Fresh chilled oysters with lemon, house-made mignonette, and cocktail sauce are served best with a cold beer at Merroir, Rappahannock Oyster Company’s restaurant in Topping.

“Those first two years, we did a lot of work refining the method,” Travis says. And it paid off. Soon enough, advances made in sorting, handling, breeding, and density control made Rappahannock one of the first commercially viable aquaculture operations in the Chesapeake. By the spring of 2004, the two felt their oysters were ready to be introduced to the world.

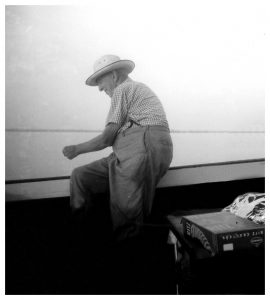

The “White Collar Oyster Man,” William “Bill” Arthur Croxton (center) always wore a suit and tie with a hat.

“We didn’t have anything to lose, so we just up and called the reservation line at Le Bernardin,” Ryan says with a laugh, referring to the number-one rated restaurant in New York City, and one of the premier eateries in the world. “We asked to speak to celebrity chef Eric Ripert—which, looking back, was completely ludicrous.” While they didn’t get through to Ripert, the two were routed to his culinary director, Chris Muller, who in turn invited them up for a tasting. “Within a week we were shipping 200 oysters a week to Le Bernardin,” Ryan says, “which was just mind-blowing.”

From there, everything changed. The cousins rounded out the year by nabbing accounts at Jack’s Luxury and Shaffer City, both in New York, as well as Washington, D.C.’s Equinox, which is owned by award-winning chef and culinary mastermind Todd Gray. Then, in November of 2005, Rappahannock Oyster Company was presented with Food & Wine magazine’s prestigious Tastemaker Award.” And the deal was sealed.

Today

Seventeen years after taking over the family lease, by all estimates the Croxtons have accomplished what they set out to do. Producing three kinds of oysters with varying degrees of salinity—the original sweet and buttery Rappahannock River variety; the slightly saltier Rochambeaus (these replaced the stingrays); and the bold and briny Olde Salts—the cousins have resurrected the native Bay oyster and put it back on the map.

In fact, according to the Virginia Marine Resources Commission, Virginia is now the top oyster producer on the East Coast. During the 2015–16 season, the Bay’s 2,000-plus commercial farmers and wild oystermen harvested more than 630,000 bushels of oysters—nearly twice the number from five years ago. Shipping well over 200,000 oysters a week, and more in a year than the entire Bay did in 2001, Rappahannock Oyster Company is spearheading the push.

“Gran” James Arthur Croxton, founder of Rappahannock Oyster Company and Ryan and Travis’s great-grandfather

After opening the Merroir raw bar in Topping in 2011 to great critical acclaim, Ryan and Travis followed up with restaurants in Richmond, Washington, D.C., and Charleston, South Carolina, and have plans to open another in Los Angeles in late 2017. Enlisting the help of celebrated chef and longtime friend Dylan Fultineer, their Richmond-based restaurant, Rappahannock, was named Esquire’s “Best New Restaurant” of 2014. More locally, Travis also owns Charlottesville’s seafood-centric Rocksalt Restaurant at Stonefield.

Additionally, the cousins have begun exporting Virginia oysters to China, Hong Kong, Colombia, and Dubai. “These places have been importing French and Australian oysters for quite a while, but now they’re beginning to go with us,” Travis says. “We’re selling on the fact that … when it comes to health standards, we are light-years above anyone else.”

What does the future hold for Rappahannock Oyster Company? Occupying the number 14 slot on Zagat’s list of “24 Restaurant-World Power Players Around the U.S.,” you can rest assured, it’s only up from here.

Leave a Reply