A cavalry engagement demonstration at a reenactment of the Battle of Second Manassas in August of 2012. The First Maryland Cavalry represented the Confederate forces, and the Second U.S. Cavalry represented the Union.

Cavalry Reenactors Illuminate History and the Bond of Horse and Rider.

Story and photography by Nancy Jennis Olds.

Hooves thundered as riders drew their sabers above their heads on an early morning. Riders galloped toward the enemy amid the echo of battle cries. They wore gray or blue woolen uniforms and kepis, pistols and carbines hung at their sides. The cavalrymen engaged their foes, their horses making quick turns. Ultimately, the warriors separated, then trotted away to a rallying point as the audience applauded the reenactor’s artful parry.

The audience was invited to meet the troopers and officers and pet the horses, a thrilling interaction for the kids. All of this happened overlooking a former battlefield in Middletown, Virginia, during the annual mid-October reenactment of the Battle of Cedar Creek. The Piedmont region is known for its love of all things equestrian: foxhunting, barrel racing, dressage, trail riding, and polo. It is this group, dedicated to emulating American Civil War cavalry, that cherishes another form of horsemanship coupled with an historical legacy.

Working with horses representing Civil War cavalry involves an investment of finances, attention to detail, time, and an adherence to a tradition beyond most of us. However, members of two very active local cavalry groups agree that this living history is a personally rewarding experience and a valuable lesson in teamwork between horse and rider.

Company H, 4th Virginia Cavalry, Black Horse Troop

Bill Scott is the commander of the unit that portrays the Company H, 4th Virginia Cavalry, Black Horse Troop, which keeps a busy annual schedule of events. The Black Horse Cavalry has participated in reenactments throughout Virginia and has been part of the Civil War’s sesquicentennial events from South Carolina to New York. Since the troupe began scheduling programs in 1999, they’ve participated in a litany of noteworthy events, such as the Manassas Civil War Weekend, the Warrenton-Fauquier County Heritage Day Parade, and the surrender at Appomattox Court House to commemorate and conclude the Civil War’s sesquicentennial.

The Black Horse Cavalry has worked with another Civil War reenactment unit, the 1st Maryland Cavalry, Company E, and “The Winder Cavalry.” Pvt. Ruth Shipley, the organization’s president, and her husband, Capt. Garrett Shipley, have participated in reenactments for about nine years. Ruth is the organization’s president and Garrett is a captain. More recently, Ruth’s father-in-law has joined the ranks, as has her father, Richard Merkel, a recent retiree and new initiate in the dismount section of the reenactment troupe.

These units are primarily portraying the Confederate cavalry, though sometimes reenactors must “galvanize,” that is, switch allegiances to level the playing field by ensuring a roughly equal distribution of Union and Confederate “soldiers.” They are careful to emphasize the historical component of the Civil War and shun extreme views and politics—both historical and contemporary.

The Independent Loudoun County Rangers

Dennis Harlow, a Culpeper resident, was the founder of the Independent Loudoun County Rangers (ILCR), a Civil War reenactment cavalry unit which represented an organization whose original corps operated around Northern Virginia. He served as its captain for 15 years. Before he considered forming the ILCR, Harlow researched the story behind the unit. The founders were primarily Quakers and German-American farmers. They were the only Virginia cavalry that fought for the Union, a perilous choice. Any native pro-Union cavalry unit would have been fighting on their own, without support from Washington, D.C. This required astounding courage both from soldiers and their families, who were often castigated by Confederate forces for their pro-Union allegiance.

Harlow says the ILCR reenactment organization spent 13 years in Front Royal participating in Civil War living history events. They traveled to Trevilian Station in Louisa County, covered the Battle of Cedar Creek for countless years, and were the first of several Civil War reenactment units to appear at Luray Caverns and the first Battle of Brandy Station. They were one of three cavalry units invited to the U.S. Military Academy at West Point, representing federal cavalry for the first time in 120 years. The ILCR also appeared on the History Channel in a reenactment of Sherman’s March. The reenactment group treasures its visits to Waterford for the annual Waterford Homes Tour & Crafts Exhibit as the original unit began its odyssey in this pristinely preserved historic town.

Training Horses for Cavalry Reenactments

“The cavalry horse changed warfare more than any other animal on the planet,” Harlow observes. It’s difficult to believe that an animal normally wary of danger would be able to endure the thick of battle with all the surrounding noise and chaos. In reenactments, there is always a lot of commotion on the battlefield, with cannons booming, muskets firing, and pistols blasting. Safety is a priority at these events—though weapons may contain gunpowder, they are not loaded with ammunition. Rarely do horses or riders lose control during the reenactment. The rigorous training provided by these organizations ensures that all participants, riders and horses, perform smoothly and safely.

There are several proven techniques that keep these horses calm amid the clamor. Ruth Shipley terms it “gun breaking.” Initially, members fire .22 caliber blanks about 30 feet away while the horses are feeding, once in the morning and again in the evening. Some horses might walk away, but their motivation to chow down overwhelms any wariness. Instinctively, horses are herd animals and may survey the reaction of other horses before deciding how to react. A horse that becomes “gun tolerant” will adjust to the noise of a weapon, but still be skittish. A horse that reaches the level of “gun broke,” Shipley says, will consistently remain calm when weapons are fired, setting an example for the less experienced members of the herd.

Part of the 1st Maryland Cavalry’s training is a competition using “Sgt. Lettuce Head,” a head of lettuce stuck on a pole lined with brass rings and balloons, which is “attacked” on horseback with sabers, pistols, and carbines. This allows the horses to become more adjusted to noise and delights spectators at events. The Black Horse Cavalry has used similar techniques, which they call “Running at the Heads,” to demonstrate the skills of horse and rider.

Although the roaring volley from a cannon seems a more frightening sound, it’s the sharp, high-pitched crack of a pistol that instantly grabs a horse’s attention, Bill Scott notes. Newly introduced riders learn that any sign of stress coming from the rider can affect the horse’s reaction to the splitting crack of a pistol’s blast. Scott will mount the the most experienced horse and fire a pistol or a cap pistol several times while remaining relaxed in the saddle. The rider communicates restraint, a forbearance that thwarts the steed’s flighty reflex to the loud stimulus. An untested rider firing a gun might tighten their knees or pull on the reins, causing the horse to become uneasy. This physical reaction disturbs the horse, increasing its anxiety and prompting a flight response. Scott always makes sure that the newest equine member and rider line up in formation flanked by two of the most seasoned horses and troopers. The new horse, sensing no signs of anxiety from its companions, will remain calm.

Scott mentions the 150th anniversary celebrations in the Manassas Civil War Days as being one of the most intense trials for his riders and horses. The Black Horse Cavalry agreed to a night ride in the reenactment camp while carrying torches and riding close to the artillery as they prepared to fire. Meanwhile, reenactors set fire to a railcar in a pyrotechnic display that added further confusion to the night. As the Black Horse Cavalry approached the flaming railcar, the artillery loosed an unscheduled barrage. Moreover, a crowd of curious spectators nearly surrounded the horsemen and their steeds. Despite the mayhem, horses and riders remained steadfast, stoic, and unperturbed, in keeping with their excellent training.

Types of Horses

Carson Smith, 10, with brother Jordan Smith, 8, pet some of the Black Horse Cavalry’s horses after a battle reenactment at Historic Sully Plantation last August.

These cavalry units are family-friendly, as Ruth Shipley will attest; her three-year-old son will always have special memories of his parents and grandparents surrounding him outdoors at various locations where they set up camp. Naturally, horses form an essential part of activities with these families and the horses are treated as family. A diverse family, that is. Though not a requirement, the Black Horse Cavalry is composed of primarily black or dark horses. Among the forty-plus members’ horses there are an almost unimaginable variety of breeds, comprising purebreds, crosses, and “Heinz 57s,” according to Scott. “It is the individual horse, it isn’t so much the breed,” explains Harlow. “Trooper and horse work as a team”

The 1st Maryland Cavalry’s horses of choice are the Tennessee Walking Horse, about 10 of 19 in total, favored because of their steady, comfortable gait and calm composure; both traits that would have been much appreciated by the Civil War soldier, although the breed had not been developed as such at the time. Garrett Shipley tried to familiarize a horse from a more recent breed of Tennessee Walkers to become “gun tolerant,” and the horse was bucking all over the place. “Man, your husband can ride!” said one awed witness as Garrett managed to hang on without hitting the ground. One member brings in his Hanoverian, a horse breed favored by European knights clad in heavy armor. “You can train any horse,” observes Ruth Shipley. “It is a matter of how you train them. You’ve got to be able to trust your horse.”

Cavalry Reenactment Costs

A new inductee to any of these cavalry groups may incur significant costs while acquiring a suitable saddle, tack, weapons, uniform, boots, canteen, and blankets. The Black Horse Cavalry provides temporary loans for some of the gear and networks with preferred vendors who offer member discounts. For example, mentions Scott, the fit of cavalry boots is important and must be just right. “We encourage new members to try the boots on before purchasing them rather than ordering by size. We caution new members to work with an experienced member and not purchase items on their own. Some vendors will just sell to less knowledgeable purchasers something inauthentic just to make a sale.”

Ruth Shipley agrees that the first-timers might be discouraged by the cost—approximately $1,200—to equip a cavalry reenactor. The 1st Maryland Cavalry also provides loaner gear such as used saddles, sabers, and guns so that new members aren’t left with a feeling of buyer’s remorse. Moreover, she acknowledges, no one should make such a substantial investment into a nonprofit, tax-deductible hobby such as a Civil War reenactment cavalry until they’re committed for the long haul. It took about six years for Shipley and her family to amass all of their accoutrements.

Scott points out that he recommends only one pistol per rider. During combat, Civil War-era cavalry rarely had the opportunity to reload. They would resort to their sabers at close quarters or use their carbines if they were at a distance from the enemy. The rangers chose Remington pistols, three per rider, and Smith carbines, said Harlow.

Derek Lanham of Co. H, 4th Virginia Cavalry, riding “Juv,” short for “Juvenile Delinquent,” during the shooting demonstration where balloons are shot while riding at a gallop.

Care of Cavalry Horses

Early on, the Confederate cavalry arguably held the advantage in caring for their horses’ welfare since most Southern cavalrymen, many of whom had grown up in the saddle, brought their own horses—which were often well-bred and well-trained—from home. The Union cavalry, in comparison, might well have been initially negligent or ignorant in caring for their horses, which were supplied by the U.S. Army. Many Union horses were underfed, rarely groomed, and miserably contained in unkempt corrals in Washington City, as our nation’s capital was then known. Sadly, a large number of these horses succumbed to malnutrition, neglect, or hoof rot. As the Union cavalry improved, better methods were employed to provide care for horse and rider alike. Horse depots were organized to exchange ill and injured mounts for fresh ones.

Due to the destitution and decimation faced by the Confederacy as the war progressed, the Confederate cavalry never had the luxury of organizing a similar system. Horses and troopers suffered from acute shortages of feed and food. With the Confederacy unable to provide fresh horses to its soldiers, “the best place to get your next horse was from your enemy,” says Harlow.

Reenactment horses, of course, are much better cared for than their historical predecessors.

Each Civil War cavalry organization maintains standards to provide for the horses’ health and safety. Regular vaccinations and excellent healthcare are required for participation. The 1st Maryland Cavalry, when out in the field, has some of their riders carry small medical bags for first aid treatment of both horse and rider. In the evening rides involving carrying torches on horseback, some riders stash a fire extinguisher in their saddlebags. Heat related illnesses could strike the rider and the horse, although Harlow claimed that horses are “tough buggers” at reenactment events.

Experience of Cavalry Horses

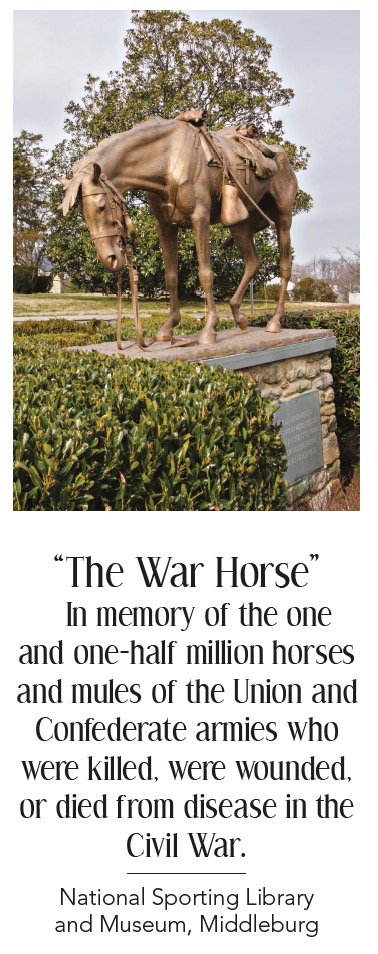

Combat was not just hell for the soldiers during the Civil War; it’s estimated that 1.5 million horses and mules were victims of warfare, disease, and starvation. Original Civil War cavalry had to contend with long rides and few breaks when on the march. Some Civil War cavalry horses never had their saddles taken off for six months at a time.They transported officers, participated in cavalry battles and raids, carried the wounded and deceased back to field hospitals, and pulled artillery and supply wagons on both sides of the conflict. They endured hunger, thirst, minié balls, and cannon fire. They sustained multiple wounds and relentlessly continued until they could go no further.

The experiences of reenactors and their horses cannot be compared to their historical counterparts. While similar cavalry training methods are used, and in themselves are historically significant (and useful in many other modern pursuits, such as large-scale livestock operations), neither reenactors or horses will ever experience the absolute horror of the Civil War: explosions, fire, injury, death, dismemberment, starvation, thirst, disease, and an omnipresent fear. Horses are terrified of fire, blood, and death, and can sense them from a great distance. They are also extremely sensitive to their rider’s emotions; reenactment horses would never have to experience the abject terror that was transmitted from rider to horse during those deadly battles.

Civil War reenactment cavalry events recall a period when horses and mules were the backbone of the military. The special bonds formed between the horse and rider during that conflict are echoed when Confederate and Union reenactment cavalry take to the field in remembrance of the enormous sacrifices that were dutifully made by cavalrymen and their horses amid the tremendous turmoil on American soil.

Excellent article. I have enjoyed keeping up with the Black Horse Cavalry over the years, since I grew up in Warrenton and was a reenactor myself. This article bodes well with the one I just submitted to you.

Thank you! I received your article and will look at as soon as I can. Thank you for submitting!

I’d love to get reprints of this article! I’m a tackshop in East Berlin, Pa where Ruth & Garret Shipley shop! (Everett too).

We get re-enactors visiting on a regular basis.

I hope to hear from you!

Lori

Tackroom Treasures

Hi Lori,

Please email Pam@PiedmontPub.com to request a copy. We’re thrilled you enjoyed the article!