Its stress-free allure goes back centuries…

By Glenda C. Booth

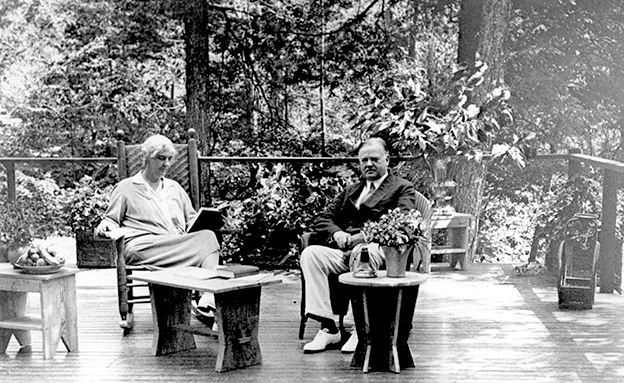

Herbert and Lou Henry Hoover relax on the porch of Rapidan Camp, Shenandoah National Park in Madison County. Courtesy of National Park Service

The peace of the Piedmont has long attracted people, including US presidents, who found respite in the area’s fresh air, gurgling streams, rolling hills, dense woodlands, and rustic fields. In sum, the region’s natural beauty and tranquility.

The White House was “the big white jail,” complained Harry Truman. Donald Trump likened it to a “cocoon.” For most presidents, the pressure-cooker demands of the office, the heavily-secured confinement, the sultry Washington summers, the need for quality down time, all drove them to find private hideaways. Four presidents downsized and unwound east of the Blue Ridge in Virginia: John Kennedy, Herbert Hoover, Theodore Roosevelt, and Thomas Jefferson.

Glen Ora and Wexford

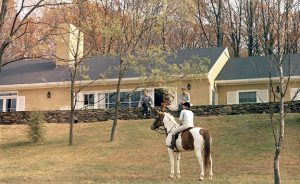

After trying the official retreat, Camp David in Maryland’s Catoctin Mountains, a woodsy enclave created by Franklin Roosevelt, John and Jacqueline Kennedy opted for 39 acres in Loudoun County, so Jackie could ride her horses to her heart’s content and daughter Caroline could trot around on her pony, Leprechaun. “I think it’s good for young children to get out of the governmental atmosphere,” Kennedy told reporters. The president had become familiar with the area as a US senator when he leased Glen Ora, a 400-acre farm near Middleburg.

- First Lady Jacqueline Kennedy sits astride her horse, Rufus, on the grounds of Wexford. President John F. Kennedy sits on rock wall with family friends, Benjamin C. Bradlee (left) and Antoinette Bradlee (center). Cecil Stoughton. White House Photographs. John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum, Boston

- Weekend at Atoka, fall of 1963. Top: President and Mrs. Kennedy, John F. Kennedy Jr., and K. LeMoyne “Lem” Billings ride in a golf cart. Cecil Stoughton. White House Photographs. John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum, Boston

In 1962 and 1963, they built a 3,500-square-foot home on 39 acres of farmland near Marshall and named it Wexford after the Ireland county of the Kennedy family’s origins. Jackie designed a stone-and-stucco, seven-bedroom, five-bathroom, one-level, ranch-style house intended to be cozy, “nothing elaborate,” said Pamela Turnure, the first lady’s press secretary. Time magazine called it “tweedy elegance.” Jackie wrote, “This house may not be perfectly proportioned — but it has everything — all the places we need to get away from each other — so husband can have meetings . . . wife paint . . . all things so much bigger houses don’t have. I think it’s brilliant!”

Jackie, Caroline, age six, and son John, age three, traveled from Washington to Wexford by limousine and helicopter. Famous for relishing her privacy, Jackie commented, “I appreciate the way people there let me be alone.” Sadly, the president only visited twice in 1963, once in October and once in November, before his tragic assassination.

The complex had a Signal Corps switchboard, a bomb shelter, stables, and Secret Service workspace. The house was built for $127,000 in 1963 dollars. In 1964, Jackie sold the property for $225,000. In 2017, it sold again for $2.9 million. The property is not open to the public.

Rapidan Camp

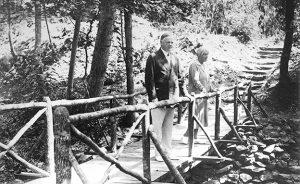

From the White House News Photographers Association Files

On the eastern slope of the Blue Ridge Mountains and in today’s Shenandoah National Park, Herbert and Lou Hoover directed the Marines to build a 13-building retreat on 165 acres, spent $5.00 per acre of their own money and named it Rapidan Camp because two streams, Mill Prong and Laurel Prong, merge there to form the Rapidan River. In choosing a site, the president had three specific requirements: at least 2,500 feet in elevation for cooler weather; within 100 miles of Washington, to get back for a crisis; and excellent fishing.

An avid angler, Hoover cast for trout amid the rocky terrain of hemlocks, pines, oaks, poplars, mountain laurels, and trilliums, where bears, bobcats, and foxes roamed. He designed the layout so that every building was within earshot of a babbling stream to “reduce our egotism, soothe our troubles, and shame our wickedness,” Hoover wrote. From 1929 to 1933, they stocked the creek, built a rainbow trout pond, and fed the fish beef hearts, treating them almost like pets. Hoover’s doctor, Dr. Joel Boone, commended the president’s ability to adjust: “The president could recuperate from fatigue faster than anybody I have ever known. He had tremendous power of relaxation once he surrendered himself to taking periods to relax and rest mentally and physically.”

- Camp Rapidan, the presidential retreat of President Herbert Hoover. Courtesy of National Park Service.

- The Hoovers at Rapidan Camp. Courtesy National Park Service

The Hoovers were rarely alone, inviting friends and notables of the era. He also used the camp for some slow-paced decision-making, a place “where no bells ring or callers jar one’s thoughts,” he said, and he believed the laid back environment fostered more thoughtful deliberations than churning Washington did. Dignitaries like Winston Churchill, Edsel Ford, Thomas Edison, and Charles Lindbergh visited. British Prime Minister Ramsay McDonald and Hoover negotiated the 1930 London Naval Treaty sitting on a log. An airplane dropped official mail daily in a nearby Marine camp.

Today, three unpretentious, wood-frame, pine cabins remain connected by woodsy paths and stone bridges. The Hoovers’ cottage was the Brown House, so named as a light-hearted contrast to Washington’s elegant White House. Visitors can explore its one story of natural wood floors, walls, and ceilings, restored to its 1929 appearance inside and out and see some original furnishings, like Lou’s desk and wardrobe. As geologists, Herbert and Lou “decorated” with rocks, shells, crystals, and fresh hemlock. They donated the camp for future presidents.

Pine Knot

President Theodore Roosevelt and his wife, Edith, decompressed in 90 acres of dense, Albemarle County woods. A high-energy man of wealth, reared in mansions and owner of one, Sagamore Hill, on New York’s Long Island, Teddy slowed down in a simple little cottage called Pine Knot from 1905 to 1908. Edith bought it “for rest and repairs,” she said.

- 1906 Pine Knot Staff. Photo by Waldon Fawcett, Courtesy of Scottsville Museum

- Exterior of Pine Knot, Theodore Roosevelt Birthplace National Historic Site. Courtesy of Theodore Roosevelt Digital Library, Dickenson State University.

Originally built as a farmworker’s cottage and largely unchanged today, the 1,187-square-foot pine and board-and-batten house has two chimneys and four fireplaces, all made of stone from Schuyler. Teddy called the cottage “only a shell of boards” and wrote, “The Tsar and Tsarina would have found it somewhat confining, since it consisted of one rough-cut, stone-chimneyed, boarded box, with two smaller boxes upstairs.” The surviving porcelain door knobs were the only decorative touch. Journalist Walden Fawcett wrote that it was “quite the most unpretentious habitation ever owned by a president of the United States.” The Roosevelts had no electricity or indoor plumbing and it was Teddy’s job to “empty the slops.” The Daily Progress newspaper reported that the house had a “meager complement of furniture,” including “a washstand of the plainest kind, probably worth a dollar and a half, and a goods box cheaply tricked out as a table.” A large farm table is the only remaining Roosevelt furniture today.

Most of the first floor is an unembellished, lodge-type room, but it was really the outside that beckoned. Spending hours rambling among the pines, oaks, redbuds, hollies, and dogwoods, Teddy, a swashbuckling outdoorsman who had killed bison in North Dakota’s badlands, hunted for Virginia game. In 1906, he wrote his son, Kermit, that he left the cabin under a brilliant moon and after 13 hours in the woods, got one turkey.

The best stress reliever for the couple was probably relaxing in rocking chairs on the porch that spanned the house’s front supported by untrimmed cedar posts, their ears tuned to birds and “little forest folk,” the president’s term. He identified 75 bird species by their call on one day and is credited with the last US sighting of passenger pigeons in 1908, birds known then to be almost extinct. In one of the three second-floor bedrooms, flying squirrels “held high carnival at night,” Teddy wrote to his son, Archie.

To get the Roosevelts to Pine Knot, railroad officials added a private car to the mail train and the couple disembarked in North Garden, a dot on the map. Then they took a carriage or horses. Teddy stopped working, put away papers and “sank” into his rustic, modest mode. They invited no notables, only one friend and their children. Theodore wrote his son, Kermit, in 1905, “It is really a perfectly delightful little place; the nicest little place of the kind you can imagine.”

Unbeknownst to the president, human critters were out there in the woods too. Edith had the Secret Service patrolling the property.

In this passage from a letter to his son, Kermit, President Roosevelt described a trip to Pine Knot with Edith.

Credit: Letter from Theodore Roosevelt to Kermit Roosevelt. Theodore Roosevelt Collection. MS Am 1541 (117). Harvard College Library.

“After dinner we went over to ‘Pine Knot,’ put everything to order and went to bed. Next day we spent all by ourselves at ‘Pine Knot.’ In the morning I fried bacon and eggs, while Mother boiled the kettle for tea and laid the table. Breakfast was most successful, and then Mother washed the dishes and did most of the work, while I did odd jobs, like emptying the slops, etc. Then we walked about the place, which is fifteen acres in all, saw the lovely spring, admired the pine trees and the oak trees, and then Mother lay in the hammock while I cut away some trees to give us a better view from the piazza. The piazza is the real feature of the house. It is broad and runs along the whole length and the roof is high near the wall, for it is a continuation of the roof of the house. It was lovely to sit there in the rocking-chairs and hear all the birds by daytime and at night the whip-poor-wills and owls and little forest folk. Inside, the house is just a bare wall with one big room below, which is nice now, and will be still nicer when the chimneys are up and there is a fire-place in each end. A rough stairs leads above, where there are two rooms, separated by a passageway. We did everything for ourselves, but all the food we had was sent over to us by the dear Wilmers, together with milk. We cooked it ourselves, so there was no one around the house to bother us at all. As we found that cleaning dishes took up an awful time we only took two meals a day, which was all we wanted. On Saturday evening I fried two chickens for dinner, while mother boiled the tea, and we had cherries and wild strawberries, was well as biscuits and cornbread. To my pleasure Mother greatly enjoyed the fried chicken, and admitted that what you children said of the way I fried chicken was all true. In the evening we sat out a long time on the piazza, and then read indoors and then went to bed. Sunday morning we did not get up until nine. Then I fried Mother some beef-steak and some eggs in two frying-pans, and she liked them both very much. We went to church at the dear little church where the Wilmers’ father and mother had been married, dined soon after two at ‘Plain Dealing,’ and then were driven over to the station to go back to Washington. I rode the big black stallion – Chief – and enjoyed it thoroughly. Altogether we had a very nice holiday.”

Poplar Forest

One hundred years earlier in 1806, President Thomas Jefferson built his retreat, Poplar Forest, on a 4,800-acre plantation near Lynchburg, where he wrote, “I fixed myself comfortably.” In fact, while president, he “invented” the idea of a presidential getaway and initiated construction. Historian Peter Hannaford has called it “the first dedicated presidential retreat.”

Courtesy of Thomas Jefferson’s Poplar Forest

Jefferson loathed Washington’s humid summers and wrote to Treasury Secretary James Gallatin, “I consider it as a trying experiment for a person from the mountains to pass the two bilious months on the tide-water.” The third president yearned to escape public life in the capital and after the presidency, the hubbub of his Albemarle County home, Monticello. His daughter, Martha, her husband, and 11 children had moved in, and unrelenting streams of uninvited guests showed up, people that his granddaughter described as “impudent and ungenteel people who behaved as if they had been in a tavern.” Explaining his need to escape to Poplar Forest, Jefferson wrote in 1812, “Here I have leisure, as I have everywhere the disposition to think of my friends.”

A self-taught architect, Jefferson studied the buildings of Europe while there five years and in designing Poplar Forest drew especially on 16th-century, Italian architect Andrea Palladio and the concept of the Roman country villa.

Jefferson observed that “all of the new and good houses” in Paris were one story, so he built his house into the crown of a hill and designed it to appear as one story from the front, but the dining room is actually two stories.

Archaeology excavation in the carriage turnaround. Courtesy of Thomas Jefferson’s Poplar Forest.

Poplar Forest is the first octagonal residence in the US. Reflecting Jefferson’s love of geometry, it is an intimate, 1,000-square-foot house filled with natural light rippling from tall, triple-hung windows on each of the building’s eight sides and a 16-foot skylight over the center, cube-shaped dining room. “Perhaps most important, the entire Poplar Forest retreat, house and landscape, radiate out from this elegant central space,” notes the website. The brick exterior has Tuscan columns, intended to convey naturalness and integrity.

Poplar Forest is one of Jefferson’s “most consummate architectural works” and “one of the most extraordinary works of American architecture,” Travis C. McDonald, Jr., the home’s director of architectural restoration, maintains.

Could these presidents really get away from it all? In 1931 when President Hoover was relaxing on his cabin porch, an 11-year-old lad emerged from the woods with a gift, a ‘possum for the President’s birthday. Today, ‘possums aren’t the problem. With 24/7 hyper-connectivity, it’s nearly impossible for presidents to truly get away. In addition to the demands of the jobs which all presidents have faced, today there are 24-hour news channels, quick-turnaround reporters, emails, texts, Twittering, tweets, instant messaging, high tech communications galore. But the peace of the Piedmont still beckons.

Visiting

Rapidan Camp

Managed by the National Park Service; Grounds are open year-round, ranger-hosted tours spring through fall. nps.gov, (877) 444-6777.

Pine Knot

Owned by the Edith and Theodore Roosevelt Pine Knot Foundation; open by appointment. (434) 286-6106

Poplar Forest

Owned by the Corporation for Jefferson’s Poplar Forest; daily guided tours March-December, self-guided tours January-February. poplarforest.org, (434) 525-1806

Leave a Reply