Hinson’s Ford

By Kit Johnston

When Union troops led by George McClellan failed to capture Richmond in the Peninsula Campaign, Confederate Gen. Robert E. Lee began moving his troops north as the Union Armies struggled to regroup. In late August 1862, Lee executed a strategic but risky plan that would pave the road to victory at the Battle of Second Manassas.

The Plan

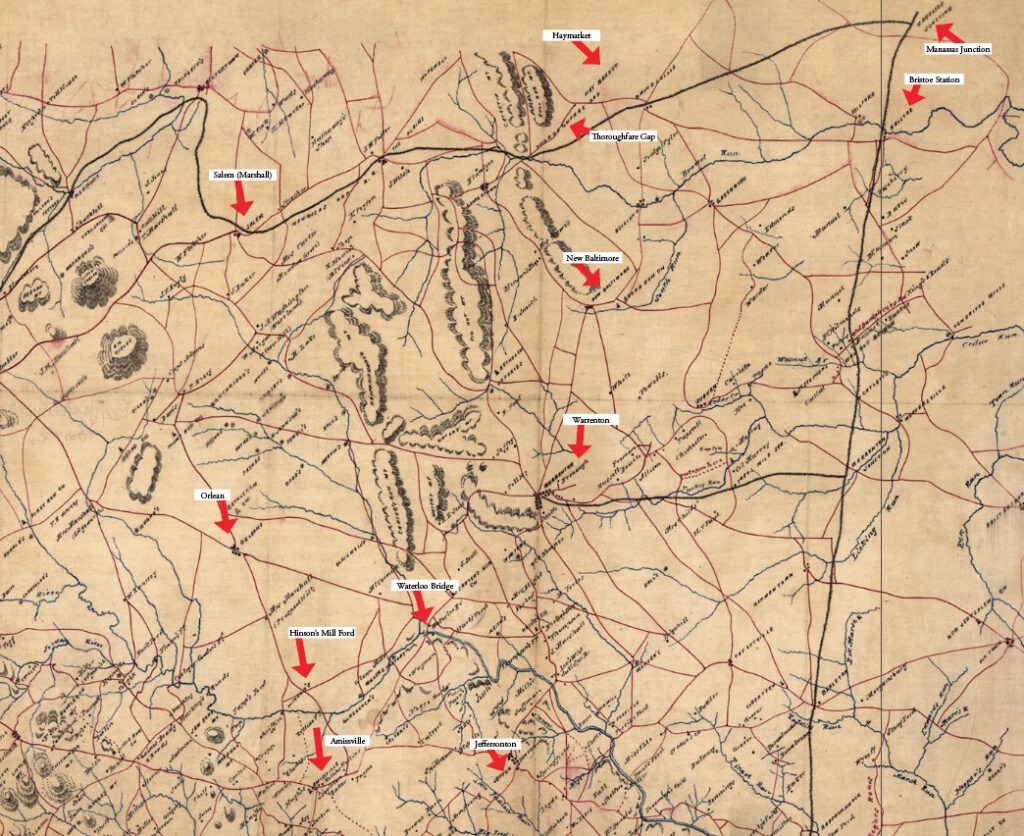

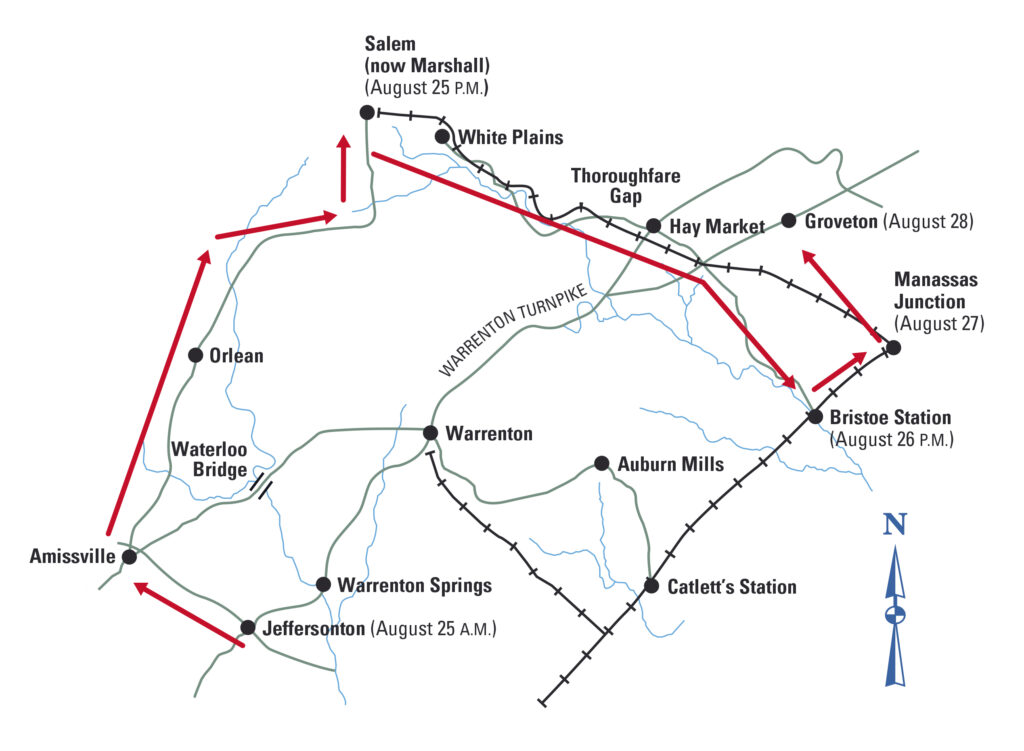

On Aug. 24, Robert E. Lee calls for a “war” council at Stonewall Jackson’s headquarters near the Rappahannock River. Jackson, James Longstreet, and Jeb Stuart attend. For days, they have tried but failed to dislodge Army of Virginia Commander John Pope from the other side of the river as he waits for Army of the Potomac Commander George McClellan to join him after the Peninsula debacle. Lee expects McClellan to show up any day, so he develops a plan for outflanking Pope’s current position so as to surprise attack his supply lines at Manassas. Lee wants to compel Pope to release his grip on the Rappahannock and thus much of the central part of Virginia. Lee orders Jackson to execute the plan. Jackson tells his commanders to be ready quite early the next day to put their 24,000 troops to the march. He asks his chief engineer, Capt. James Keith Boswell, to map the quickest and safest route for the men to take to accomplish Lee’s goals. The young man from Fauquier County maps out such a route, Jackson approves it, then tells Boswell to prepare to lead the large column before daybreak.

Rousted from their bivouac near Jeffersonton at 3 a.m. Jackson’s wing of the Confederate Army prepares to march to the Rappahannock Turnpike. At the Turnpike (now Rt. 211), they will turn west, march just past the sleepy post office village of Amissville, then turn north onto Hinson’s Ford Road to cross the Rappahannock River at its upper reaches.

“I Heard Them Coming”

By Kit Johnston

I was sitting on my front porch just before dawn when I heard them but couldn’t quite see them. Suddenly, wave after wave of men began marching by, led by a handsome young captain I recognized. It was James Keith Boswell! We’d met at Hinson’s Mill Ford not long ago, both of us crossing from the Rappahannock side of the river to the Fauquier side, me to sell the last of my corn at the Orleans market, he to visit family. We knew well this crossing at old man Hinson’s mill because it was much closer to Orleans than the Waterloo Bridge. Plus, there were Yankees at that bridge.

The men kept coming for hours. As the sun rose, most seemed thirsty, likely hungry, too. I had no food to spare, but I had water and passed the bucket to the boys until an officer came and told them to ‘close it up.’ When he moved on, I asked a soldier where he was going. He shook his head. ‘I don’t know, but it doesn’t matter. We’ll follow Stonewall wherever he leads, no matter what.’ The men had had no fires that morning, which meant no coffee and barely a piece of hardtack. They were told to pack what food they had then send their haversacks to the wagons to carry. When the column turned west, the men felt hopeful. Perhaps they were headed back to the Shenandoah Valley, but then the column turned north to take my road, the road to the ford.”

The Ford

When the column arrived at the ford, Capt. Boswell plunged in first, then pulled up on the other side to summon the cavalry to receive orders. Hand-picked by Jackson for their knowledge of the countryside between the ford and Salem, these men were to serve as advance pickets, rear pickets, and messengers among Jackson, Lee, and Longstreet. In addition, they were to find shortcuts in Boswell’s route, if possible, for Jackson expected the entire column to make Salem (now Marshall) that night.

Next, the infantry entered the water wearing their clothes and boots, as instructed, for speed. Suddenly, all came to a standstill when the artillery wagons carrying some 80 guns began to bog down on the north bank. Even officers dismounted to free them.

Not long beyond the ford, the column entered the quaint old village of Orleans. Residents flocked from their homes and storefronts to cheer as the men strode by. Young women waved and handed out food and water. And the soldiers appreciated it, particularly the food, but it did slow them down. They worried, and knew Jackson did too, that the longer they tarried the better the chance the Yankees had of detecting them.

Fears of detection were not ill-founded. In fact, just that morning from a hill high above the Waterloo Bridge, Union Col.l John Clark of Gen. Nathaniel Banks’ staff had seen Confederate infantry and artillery moving from Jeffersonton toward Amissville then, later, evidence of troops moving north or northwest “with colors flying.”

Clark reported back to Banks. Banks reported to Pope that the enemy might be moving to the Valley, possibly with “designs [on] the Potomac.” Pope told Washington that if he could verify this, he would send Gen. Irvin McDowell’s Corps to deal with it, but then he did nothing, giving Jackson “precious hours of unobstructed march,” according to John Hennessey, author of Return to Bull Run: The Campaign and Battle of Second Manassas.

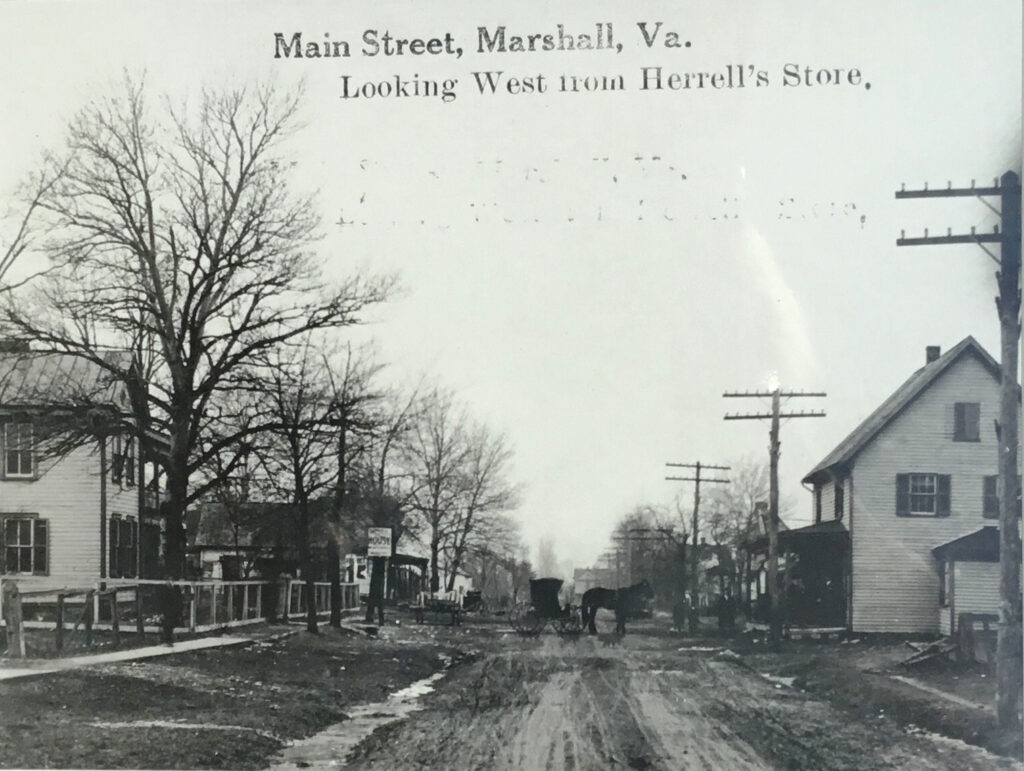

Near Salem and bivouac for the night, Jackson dismounted to climb a rock to watch his men. They began to cheer, but he quieted them, so they tipped their hats instead. Not a man to gush, Jackson nonetheless said, “Who could not conquer with troops such as these?” It is likely he included his division commanders in his unusual praise. First in the lineup at that time was Richard Stoddert Ewell, a reliable commander who had performed well in the Valley Campaign and had yet to suffer a serious reprimand from Jackson. Next was A. P. Hill of Culpeper, commander of the largest division in Jackson’s wing, and in Jackson’s estimation, the best. A handsome, aggressive West Pointer (like so many officers on both sides), Hill had feuded with Longstreet and so was reassigned to Jackson. Last were Brigadier Gen. William Taliaferro and his division, which he had inherited from Jackson. Born to a prominent Virginia family, Taliaferro was the first civilian soldier to serve in such a high position under Lee. His relationship with Jackson was a bit up and down, but they shared an appreciation for hand-to-hand fighting. That evening, Taliaferro’s division rolled into Salem around midnight, his men falling asleep on whatever patch of bare ground they could find.

Clear Sailing to Gainesville and Beyond

Early on Aug. 26, Jackson’s column left Salem to march again, still not knowing where, until Ewell’s Division turned the column east toward Thoroughfare Gap. The men were still moving briskly at three miles an hour, but their condition was not good. “Many were barefoot,” one of Hill’s men reported later, “Many more without a decent garment to their backs, more still ill with diarrhea and dysentery and all half-famished.”

Fortunately, the men got a big break when they reached the Gap, for there was not a Yankee in sight for them to fight. A narrow and steep defile between the Pond and Bull Run Mountains, the Gap was a natural place for the Union to try to stop Jackson. But by the time the column arrived, any Union presence that might have been there was gone, withdrawn or fled.

Jackson and his men sailed on, reaching Gainesville by 4 p.m. after covering 47 miles in a mere 36 hours. Yet Pope still believed Jackson was actually in the opposite direction headed west out there somewhere despite intelligence to the contrary. The time had come to attack Pope’s lines of supply and communications on the Orange and Alexandria Railroad (OARR).

Jackson Attacks

The first target of Jackson’s attack on the OARR is Bristoe, a small station down the line. Jackson’s men encounter little resistance there as they proceed to derail one train and cause two others to crash into each other. Then they tear up a considerable portion of track. The next stop is Pope’s main supply base at Manassas Junction. Despite its value, the base is guarded by only 115 infantrymen, a rookie regiment of Pennsylvania cavalry, and eight cannon. Jackson orders a night attack. His men take the base in five minutes at the cost of two men wounded and two men killed. They capture 300 soldiers, pilfer valuable guns and much needed food supplies, cut Pope’s communication wires to Washington, then torch the place.

Longstreet and Lee on the Way

On the same day Jackson makes his move, Longstreet and Lee make theirs. At a leisurely pace that does not immediately arouse Union suspicion, Longstreet withdraws from his position on the Rappahannock River where he had been decoy fighting with Gen. Banks. Longstreet then joins Lee in following Jackson’s route to Manassas. Longstreet, Lee, and 28,000 Confederate troopers spend the first night of their march in Orleans with the intention of reuniting their men with Jackson’s as soon as possible.

From late in the evening of Aug. 26 through Aug. 27, a large number of Union troops try to trap Jackson at Manassas Junction. The problem is, he isn’t there. He has quietly moved with his men in three columns to secluded woods northwest of Groveton village at the crossroads of Sudley Road and the Warrenton Turnpike. Jackson’s and A. P. Hill’s divisions are still there the next day (Aug. 28), while Ewell’s and Taliaferro’s divisions rest a few miles away, at Matthew’s Hill.

The First Shots at Brawner Farm

On Aug. 28, toward evening, Jackson is on his horse watching the Turnpike below when he spies a Federal column from McDowell’s Corps. He decides now is the time to strike. He calls for Taliaferro and Ewell to come quickly to lead an attack. By the time they get there, the column has disappeared. Suddenly another column appears, four brigades of 6,000 men from Gen. Rufus King’s division strung out nearly a mile on the Turnpike. The soldiers have dropped their guns to their sides and slowed to “route step,” for the sun is setting, the air is still, and as one man later wrote, “No one dreamt of the danger and death in those quiet woods.”

Taliaferro and Ewell attack swiftly. They have the high ground and tactical advantage. Their artillery is well placed on the ridge, its aim deadly accurate. It is an exceptionally fierce firefight, some at close range, and Union Brigadier Gen. John Gibbon’s command bears the brunt of it. Darkness falls, and the fighting at Brawner Farm ends after 90 minutes. Ewell lies severely wounded. Each side has suffered some 1,000 casualties.

Meanwhile, Lee and Longstreet have a problem. McDowell (without telling Pope) has sent Brigadier Gen. James B. Ricketts and 5,000 men to try to stop them from getting through the Thoroughfare Gap. However, Ricketts arrives too late because Lee and Longstreet are already there, and after some successful outflanking moves by the Confederates, Ricketts retreats. Now on the other side of the Gap, Longstreet can hear the sound of heavy firing from Jackson’s position. He resolves to reach Jackson by the next morning.

Pope Attacks

On Aug. 29, Pope opens the second day of the Battle of Second Manassas with a series of piecemeal attacks against Jackson’s troops, well placed behind the fills and deep cuts of an unfinished railroad.

National Park Service (NPS) historian Jim Burgess noted in an interview a few years ago that the unfinished railroad provided the Confederates with a strong defensive position that spanned several miles from below the ridge near Brawner Farm to Sudley Church and nearby Matthew’s Hill; there were ways to escape to the west, if needed; and Longstreet is on his way. Burgess credits Longstreet’s arrival in the morning of Aug. 29 for setting “the stage for Pope’s [ultimate] defeat.”

In four separate piecemeal attacks on Aug. 29, the Union achieves some breakthroughs in the Confederate line. Pope could have pursued those breakthroughs. But he doesn’t, NPS volunteer Steve Herholtz notes in his talks about the battle, because Pope is counting on a major attack by Maj. Fitz John Porter’s 5th Corps.

But the attack never comes. Porter’s troops fail to show. Longstreet had met them near Gainesville with a deterrent force some say was 30,000 strong. McDowell knew by early afternoon that Longstreet had arrived and could present a problem. But Pope doesn’t know that, not until almost midnight.

The Final Blow

On Aug. 30 close to 3 p.m., Pope orders Porter to strike Jackson’s line with up to 10,000 men near a deep cut of the unfinished railroad. The assault is the largest Union attack of the Battle of Second Manassas, and it quickly fails, causing disarray in the Union Army. Gen. John Reynolds’ Division of Pennsylvania Reserves is called away from protecting the Army’s left flank to provide cover for troops retreating from the failed attack.

About 4p.m., Longstreet launches a counterattack on the Army’s vulnerable left flank, which is now protected by only two brigades: Col. Gouverneur Warren’s New Yorkers and Col. Nathaniel McLean’s Ohioans. A fight ensues on a place called Chinn Ridge. The fight lasts only 90 minutes, but that is long enough for the Union Army to develop a makeshift defensive position on nearby Henry Hill. The Confederate Army will ultimately prevail this day, but the ridge fight has weakened its organization and timing. By the time the Confederates are ready to mount an assault on Henry Hill, the Union has greatly strengthened its position there. As darkness falls, the third day’s fighting ends.

That night, Pope withdraws to fortifications in Centreville. His decision is controversial, but some say it is needed to save his Army. The casualties count for the Battle of Second Manassas are some 14,500 Union troops and some 9,200 Confederate troops dead, wounded, missing, or taken prisoner.

Postscript: The Confederate victory at Second Manassas emboldened Lee and provided the springboard for the South’s first invasion of the North, the Antietam Campaign. Meanwhile, Pope was relieved of his command and sent to the West to quell Indian uprisings.

Civil War Trails is the world’s largest “open air museum.” Ever-growing, we currently offer more than 1,350 sites to explore across six states. Virginia offers more than 500 Civil War Trails sites with at least two dozen in Rappahannock County, including Hinson’s Ford.

At each site our signature directional signs will welcome you and a Civil War Trails branded interpretive sign will provide the fuel for you to imagine the historic events. Each site is promoted internationally through the distribution of our brochures, our partnership of more than 500 municipalities and state travel offices. This ensures that our educational product is also a viable part of the local economy, driving travelers to stand in the footsteps of history.

Civil War Trails offers something for everyone. You can drive the Gettysburg campaign turn-by-turn, paddle of Frederick Douglass’s birthplace, hike to Confederate artillery positions on mountaintops, or explore quaint downtowns. As you follow Civil War Trails you will also stumble upon local wineries, B&Bs, live music, farm stands, antiques, and vistas which will always appear sharper in your memory then on your phone’s camera.

Leave a Reply