Inspired by women, the paintings of Judith Thompson transport viewers to timeless realms of playfulness and childhood joy.

By Eric Wallace

Stepping into Purcellville-based painter Judith Thompson’s Ship Hill Studio, one is struck by an array of fantastic color and imagery. Big, wall-gobbling, five-, six-, and even eight-foot cavasses confront the viewer with fantastic worlds and sleek elongated characters that seem to have been plucked from a dream authored by a team of Mexican muralists, surrealists, Fauvists, and Dr. Seuss. However, phantasmagoric as they may be, the scenes appear more whimsical than malicious, evoking rather a sense of playfulness or adolescent mischief than anything nightmarish or ominous.

Stepping into Purcellville-based painter Judith Thompson’s Ship Hill Studio, one is struck by an array of fantastic color and imagery. Big, wall-gobbling, five-, six-, and even eight-foot cavasses confront the viewer with fantastic worlds and sleek elongated characters that seem to have been plucked from a dream authored by a team of Mexican muralists, surrealists, Fauvists, and Dr. Seuss. However, phantasmagoric as they may be, the scenes appear more whimsical than malicious, evoking rather a sense of playfulness or adolescent mischief than anything nightmarish or ominous.

“It’s not that I have a prejudice against work that expresses darker emotions,” says Thompson. “But each of these pieces takes a very long time to produce, and I find it hard if not impossible to work if I’m not enjoying myself. If it’s not fun and I’m not laughing and having a good time making it, chances are I’m going to trash the thing and go in another direction.”

The results of Thompson’s approach are various, but tend to range between two poles. On the one hand, she presents what might best be described as a pastoralizing of childhood reverie. On the other, a feminine maturity that is, paradoxically, both soothing and unsettling.

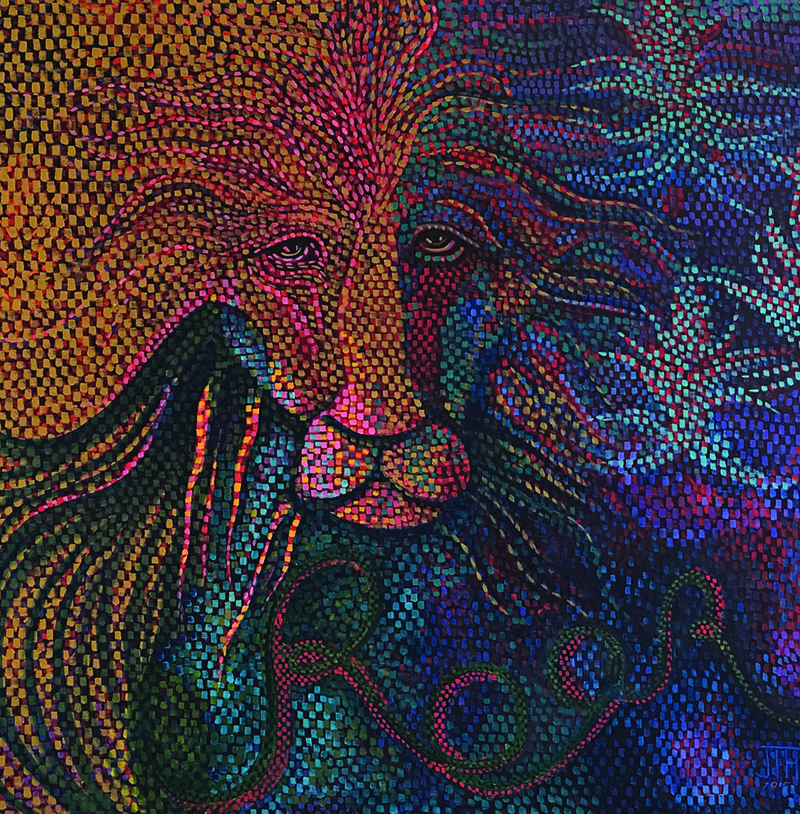

Roar

Strikingly, nearly all of the paintings feature women as their central characters, with many being either flanked or accompanied by an animal. The faces of the women—and, for that matter, the animals—are calm to the point of appearing opiated, ethereal, otherworldly. Suspended in a timeless dreamscape, while occupying fleshly forms, their perfect posture and serene expressions channel the divine.

While the attention of younger figures tends to fix on other objects and tasks (see Hoopla, for instance), in works like A.W.E., the older woman’s eyes seek the viewer, not so much questioning as simply peering into him or her. Encountering the respite of a realm free of fourth-dimensional constraints, the effect is mesmeric. As if we are but passerby before a window, the women humor our momentary presence. The slight, upward turn of their mouth alluding to a world that we long to enter but cannot.

A. W. E.

“I am inspired by women and, generally speaking, femininity,” says Thompson. “When I work on these paintings, I feel this deep serenity. I’m drawn to woman’s role as protector and nurturer, and, when I add the animals, it’s almost always a means of emphasizing that aspect. So while, yes, they are my creations, for me, being in the presence of these women is very soothing, very safe-feeling. I get very quiet and open myself, and I experience this sense of incredible freedom. And that’s what I try to put into the paintings.”

According to Thompson, who does not paint men, her interest in female subjects stemmed from her Connecticut childhood, specifically her experiences with her mother and grandmother.

“My penchant for the arts became apparent about the time I turned six and [it] quickly took the form of an almost obsessive precocity,” she says with a chuckle. “Like most kids, I started off drawing, only, once I got started, I couldn’t stop. It’s all I thought about. All I did. I’d go outside to play, but would come back itching to draw what I’d seen or found. I’d wake up in the morning and the first thing I’d do was draw my dreams. I literally filled hundreds of sketchbooks. My life centered around it.”

Meanwhile, Thompson’s reproductions were uncannily good. Her sketches of her mother, father, and five siblings looked more like real people than stick figures. She sought to render birds with feathers and shading as opposed to inverted, oblong horseshoes. Astonished by the child’s ability, her grandmother and mother supported her wholeheartedly.

Hoopla

“Their biggest contribution was a surety that I always had an appreciative audience,” she says. “But they also encouraged me by buying supplies and making sure I had access to all kinds of materials. From very early on, every birthday and Christmas gift was an art item!”

Throughout high school and into college (where Thompson earned a BFA from Syracuse and an MFA from Temple University, both in sculpting), despite being singled out and mentored by a handful of teachers, the two women remained Thompson’s foremost pillars of support.

Then, something happened. Within a short span of time, she lost them both.

“When my mother and grandmother passed I felt very, very alone, like the tie with everything I’d known and been was suddenly and permanently severed,” Thompson confides. “But I knew that I had to keep moving forward, that more than anything they’d wanted me to pursue my passion and become a professional artist. So that’s what I did.”

Only, although their lives had been extinguished, the women insisted on coming back—albeit in a different form. Without planning or premeditation, images of her grandmother and mother’s faces kept surfacing in Thompson’s work. Not one to shy from inspiration, she decided to delve deeper.

“I felt very ill at ease at the time and found that, when I painted my mother and grandmother, it opened a door to a kind of safety,” she says. “I realized I’d spent a lot of time as a child making art in their presence, and I always felt so happy and safe and protected in that space. When I began to put them in the pieces, that feeling returned.”

Without intending to do so, Thompson had stumbled onto a way to honor her mother and grandmother’s contributions to her life and access the sanctity they’d provided her throughout her childhood and adolescence. As she developed the style, the women in the paintings morphed and changed, but continued to serve as guardians. “I paint them idealistically as safe, steady and ever-present,” she explains. “Their presence nurtures me and helps me embrace challenges and successes without fear, and pushes me to continue moving ahead with my art.”

Between Ship Hill’s larger pieces hang smaller studies of objects, animals, and landscapes that, despite appearing to be mosaics, are actually paintings. “This newer work features an experimental mix of enamel and oil paints, and it’s something I’m rather enjoying,” says Thompson, pointing to a 36-by-36-inch piece titled Roar, a facial portrait of a quiet-eyed lion rendered almost entirely of small vertical rectangles of alternating color. By stacking layer after layer of brushstrokes, Thompson’s rectangles take on a raised texture and look like ceramic or glass tiles.

As the latest of a long line of innovations, the new technique is welcome. After seriously studying ceramics in high school and sculpture in college, Thompson worked for years in a bronze foundry, then as a clothing designer, making clothes out of building materials. Always looking for the next thing, she transitioned to painting about 20 years ago. Constantly experimenting, she follows her good-timing muse wherever it may take her.

“I’m in the studio five to seven days a week, eight hours a day, and this is how I make my living,” she says. “However, while I support myself by selling art, I find it extremely important that the work never fails to be surprising or enjoyable. I want to feel validated by my efforts but, even in the most challenging of circumstances, I want to be having fun as I’m creating. If I’m not enjoying myself, I cut my losses and start looking for a more pleasurable route.”

Leave a Reply