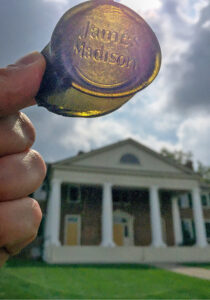

A shard of a wine bottle made of olive green glass showing the Madisons’ seal, found in the South Yard. Until about 1800, the “I” was commonly used interchangeably with “J”. The “I” as the first letter on this seal dates the bottle to the President’s father.

Telling a more complete story

By Glenda Booth, photos courtesy of James Madison’s Montpelier

A tiny bead, a rusty nail, a needle-sized fish bone, a dirty shard of glass. These are probably trivial objects to the average person, but to archaeologists at Montpelier, they are significant and exciting. Buried in the dirt are many stories of life on an 18th-century, Virginia plantation — the masters, the overseers, and the enslaved people. Thousands of dirt-encrusted artifacts as small as a pea can reveal what people were doing and perhaps why. Montpelier is the home of the fourth U.S. President, James Madison, and his wife, Dolley, near Orange, and in their day, up to 135 others, 120 of whom were enslaved.

A wine seal beginning with the letter “J” dates it to the President’s time

Since early 2009, Montpelier has hosted and trained around 1,400 volunteer archaeologists annually to help with excavations. Participants gladly spend hours on their knees or crouching in a five-by-five-foot pit, trowel in hand, patiently, painstakingly scraping in the dirt around the mansion’s grounds or out at a farmyard’s edge, where slaves swept and left debris.

Charlottesville resident Marie Hartless learned how to clean an iron hatchet head, how to identify types of nails, and whether they were made by hand or machine, based on their shapes. Hartless’s ancestors were the Madisons’ neighbors.

Emily Cockrell, from Glen Allen, came upon a small blue bead, a straight pin, and button pieces when sifting through some pebbles. “There is something extremely exciting about finding pieces like those because they are so intimate to their user. Who wore this?” she asks.

Dean Cummins, a 12-time volunteer from Reston, says his most exciting artifact was part of a glass wine bottle bearing the Madison seal. “I feel like I’m contributing to the research in a small way, I keep going back because there is always something new to learn,” he comments.

Archaeology Informs

In a typical year, between 120 and 150 archaeology volunteers seek clues of plantation life at Montpelier, led by Dr. Matthew Reeves, director of archaeology and landscape restoration. “Understanding what it looked like in the 1820s is not just for book knowledge but will help the public understand life then,” he explains. “If the buildings are not visible, people don’t know.”

James Madison (1751-1836), president from 1809 to 1817, was hailed as the “Father of the Constitution and the Bill of Rights.” He co-wrote The Federalist Papers and was the fifth secretary of state from 1801 to 1809. Madison grew up at Montpelier, lived there as an adult, and returned after his presidency. Dolley made her mark, too, holding then-unprecedented, bipartisan social affairs in the White House and whisking Gilbert Stuart’s portrait of George Washington away in 1814 when British troops neared Washington, D.C.

- Shards of ceramic teawares found in the South Yard dates that were purchased and used by enslaved individuals in the 1810s. The piece on the left was manufactured in England and is a hand-painted coffee cup while the fragment of the right is Chinese-export porcelain. By selling or bartering produce at the local markets, the slaves could earn money for such things.

Of the thousands of objects the Madisons owned, surviving ones are “barely enough to fill a room,” says Reeves, and many of Madison’s personal papers were destroyed. Archaeology offers seemingly mundane but critical details of life 200 years ago and artifacts can often be the only source of information. In trash deposits, archaeologists may find chimney bricks or door hardware, for example. Excavators have found Parisian porcelains there, offering hints about mealtime in the main house. From artifacts, researchers learned, for example, that the Madisons regularly served suckling pig and veal to show off their wealth and that enslaved girls played with dolls to learn how to care for their mistress’s children.

- A doll’s foot and hand found in the South Yard near the house slaves’ quarters. These doll parts likely were in the quarters as young enslaved girls played with dolls in preparation for caring for the owner’s children.

Beyond the Mansion

Initial digs focused on the historic core, including the mansion, its immediate surroundings, and the formal grounds, but those excavations only tell part of the story. Around 120 enslaved people labored there, the human engines that made the plantation function. They had lives too, but their stories rarely made it into historical accounts. Madison’s surviving papers have scant details on their lives.

A shard of china found in a trash deposit near the main house. It belonged to French porcelain dinner set the Madisons purchased in 1803 and used while at Octagon House, the temporary home of the president after the White House burned during the War of 1812. The dinner set was used as State China in Washington D.C. from 1812-1816, and brought back to Montpelier when Madison’s term was finished.

At slave-dwelling sites, archaeologists have found “treasure troves” of British-manufactured ceramics, bottles, jewelry, animal bones, nails, hardware, chimney bricks, and stones. One especially poignant find near a slave-dwelling site was a pipe bowl bearing the word “Liberty,” an ironic label at the home of the slave-owning Father of the Bill of Rights. “These pipe bowls demonstrate that the enslaved community had their own ideas and concepts about politics, and that they were political agents as well, despite not having the political rights afforded to others,” Terry Brock, Assistant Director of Archaeology, has observed.

Exploring slavery motivated Washingtonian Victoria Elliott to volunteer three times at Montpelier. “It’s a combination of doing something outdoors and physical in the fresh air, and at the same time it’s intellectually interesting. We are always learning about the institution of slavery as it was practiced at Montpelier,” she offers.

Montpelier has reconstructed six slave dwellings based on archaeological research. This fall, volunteers are learning to use 19th-century construction techniques to make tables and chairs for cabins in the South Yard slave-living area. Some help build timber-frame, ghosted structures without doors or windows to represent slave quarters.

Expedition member Sandra Hesse getting ready to sort and wash artifacts in the field lab, which is now held outside during the pandemic.

Now archaeologists are working on the 70-acre “Home Farm” to better understand the overseer’s role and the plantation’s agricultural practices. On southern plantations, overseers managed day-to-day operations, especially the enslaved people. He was often a white, middle-class man and this job has been “under studied” by historians, some argue. Researchers are trying to answer several questions, including how the overseer established control over the enslaved laborers and their power negotiations. The “Home Farm” included the overseer’s house, barns, horse and livestock paddocks, a blacksmith shop, and a mill. For clues, excavators are trying to reveal hearths, chimney bases, post holes, building footers, and trash pits, for example. Excavating the home farm and up to 20 dwellings there can “provide an even fuller story of the world at Montpelier,” says the website.

In addition to excavating, volunteers learn to identify, clean, mend, conserve, analyze, and catalog artifacts. Some volunteers learn metal detecting. Some work in the laboratory there. Every hour of excavation requires 20 hours of archaeology lab work, say experts.

Working with the Descendant Community

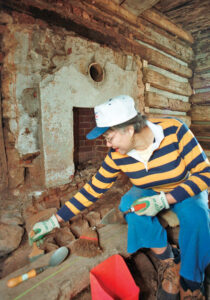

Rebecca Gilmore Coleman, granddaughter of George Gilman, a freedman formerly enslaved at Montpelier, excavating the hearth at the Gilmore Cabin.

Recognizing that Montpelier was much more than the Madison family and their mansion, today’s managers have made other efforts to tell a fuller story. They have connected with descendants of former slaves and collected oral histories from people who trace their roots to Montpelier. In the early 2000s, they connected with Rebecca Gilmore Coleman, granddaughter of George Gilmore, a freedman formerly enslaved at Montpelier, and restored the Gilmore family cabin, across from the estate’s entrance. On the involvement of descendants, Reeves believes, “The community guides our interpretive efforts, aids in our understanding of slavery and the African American psyche of the time, and gives a different perspective on the lives of the people we are striving the humanize and understand.”

Archaeological research also supported the exhibit titled “The Mere Distinction of Colour” in which living descendants of the enslaved relate their ancestors’ experiences there. The exhibit also traces the history of slavery in America and its lasting legacy.

In hopes of telling a more complete story, archaeologists are literally unearthing history at a place where the fundamentals of freedom may have been conceived, but were denied to those in bondage. “This isn’t African American history,” says Hugh Alexander, a descendant of Paul Jennings, one of Madison’s enslaved servants. “This is American history.”

Archaeology Expedition Programs

Expedition member Carissa Trotta and Staff member Hannah James doing measurements for a drawing of the site.

The staff at Montpelier Archaeology have a passion for working with the public to discover and preserve Madison’s historic landscape. They welcome members of the public to participate in week-long family-friendly immersive programs where you will step inside the active excavation sites and dig beside their professional archaeology staff.

Along the way, expedition members will learn how to identify 18th and 19th century artifacts and discover what happens to this material culture after it is excavated.

The programs also include several specialty lectures and tours that are not available to a typical Montpelier visitor that will immerse you in the 18th, 19th, and 20th century history of the property.

You will not just dig with the staff, you will learn with them as well. No prior experience is necessary, and those ages 12-90 who are willing to get a little dirty are welcome.

Information and fees can be found at montpelier.org/visit/excavate-field-expedition

Leave a Reply