Changing times and the role of authenticity

By Scott Elliff, Photography by Jaclyn Dyrholm

My first article for The Piedmont Virginian was written in 2010 when I opened DuCard Vineyards as a Virginia farm winery. Lots of water has flowed under the bridge since then. And we’re both still here! We have grown and evolved: The magazine is now bi-monthly, adding features and staff while keeping the same fabulous content and photography that showcases our great region. At DuCard, we’ve doubled the acreage of grapes we grow, expanded facilities three times, and added new wines, a wine club, food and wine pairing programs, seated tastings, vertical tastings of old library vintages, and more.

There are more and more options for consumers today, of course, whether media or beverages. Magazines and newspapers, sure, but also social media, blogs, e-zines, and digital content of all kinds. Farm wineries (like us), yes, of course, but also cideries, urban microbreweries, “farm breweries,” and distilleries.

A major challenge in these competitive arenas is to differentiate yourself and appeal to a particular niche market of some kind. At DuCard, we have emphasized our image as a boutique winery, operating in a “green” and sustainable fashion in a gorgeous mountainside setting. We offer artisanal, high-quality wines made from grapes grown and lovingly tended here at our vineyard. We make our wine the old-fashioned way—in small quantities that are sold only on-site at our tasting room where we concentrate on a providing a personal and memorable consumer experience. That’s a mouthful, but we have been able to stick very closely to it.

The personal connection formed with customers is DuCard’s hallmark; staff member Javier Luces personally pours a tasting for guests.

Historically, pretty much the entire Virginia wine industry pursued this niche. To go wine tasting meant a trip to the countryside to look out on vines. and rub elbows with the winemaker, who was often also the owner and vineyard manager as well as the one pouring the wine in the tasting room. You would get to taste the local wines while enjoying music and other appropriate on-site events that the Virginia legislature has uniquely allowed “farm wineries” to do, with few local restrictions, in order to enable our growth and provide this rural experience. You’ll still find many of the pioneers who laid the foundation for the industry involved at the older wineries in the state—grape growers, winemakers, and visionaries on whose shoulders we all stand. Even today, the trade’s motto is “Virginia Wine: True to Our Roots.”

But the landscape is changing.

Every day, someone asks me in the tasting room: Do you grow your own grapes? Do you make the wine yourselves? here on the property? Wow. Uh, yes, and yes. Of course. Until the past year or so I never heard anyone pointedly ask that. Maybe consumers are becoming savvier about the changes that are going on.

It’s becoming big business, with 6.6 million bottles of Virginia wine produced last year, over two million visitors coming to our tasting rooms, and overall economic impact measured at more than a billion dollars. And, maybe not surprisingly, new ways of operating are being launched by a new generation of business-savvy and well-capitalized entrepreneurs.

It’s becoming big business, with 6.6 million bottles of Virginia wine produced last year, over two million visitors coming to our tasting rooms, and overall economic impact measured at more than a billion dollars. And, maybe not surprisingly, new ways of operating are being launched by a new generation of business-savvy and well-capitalized entrepreneurs.

There are now “Virginia farm wineries” that grow few of their own grapes. They are not a farm, and they let others worry about the pesky farming details: frost, humidity, mildew, harmful insects, hurricanes, tractor maintenance, labor availability, and all the rest. By using “leases” of other off-site properties on which grapes are grown, they can still call the fruit their own. And, by the way, some of that fruit is coming from California to boost production, too.

There are now “Virginia farm wineries” that grow the grapes, but don’t make the wine that has their name on the label. By outsourcing the winemaking to others, they don’t have to invest in expensive equipment—tanks and barrels and all the rest—and don’t have to deal with the inevitable vagaries, risks, and challenges of processing, fermenting, and aging the wine.

These folks often are planting some grapes, and may be planning to build their own winery later, but the attractiveness of these approaches might mean they won’t end up doing so.

Maybe I should be jealous. It all sure seems “easier” than the dirty-fingernail, sweat-the-details work that we’re doing every day at DuCard in the vineyard and the winery. These new-style operations, often elaborate wine-themed bars located close to major population centers and using the same “farm winery” privileges, can start selling and getting a return on investment right away, without having to wait years for new grapevines to produce grapes and then wait further to make and age the wine before selling it. Weddings and large events can provide great cash flow too, with wine sometimes being a secondary or supporting activity.

Contracting out to experienced, and in some cases nationally and internationally known winemakers located elsewhere in Virginia, certainly helps improve overall wine quality and enables us to better compete against France, California, and others (although we’re doing pretty well in that regard already). Growing the grapes in off-site locations allows new vineyards to be situated in the most suitable (and lower cost) places, spreads weather-related risks across multiple sites, and enables economies of scale that drive operating costs down.

Okay, so these guys are smarter than I am, I guess. Are these new business models popular and successful? Sure, look at the crowds. But I think something is getting lost along the way. They just don’t seem authentic.

In these new-style operations, the consumer is probably not going to meet the guys tending the grapes or the woman (yes, increasingly so) making the wine—or experience the passion they bring to their work. The owner is unlikely to be found walking around on the patio, chatting with customers, sharing personal history and answering questions. The bar staff is less likely to know details about the wine or be personally involved with the grape growing or winemaking. There’s less of a connection with the unique aspects or sense of place (terroir is the famous French term for it) associated with where the grapes were actually grown. And that annoying or inconvenient trip out to the boonies no longer becomes necessary—although, ironically, it’s what often fulfills the soul, helps reconnect with nature, and provides a welcome glimpse into a more traditional lifestyle.

DuCard’s rural location bordering Shenandoah National Park in Etlan enables them to enhance their guests’ experience at their boutique farm winery.

Our industry is not blind to the issues. We need to evolve and want to continue to be a great success story for Virginia. But common sense dictates that to be a “Virginia farm winery” you’ve got be farming grapes. You, yourself, need to be producing the wine that reflects your unique location and style. What has made us popular to date has been the full authentic experience, not “just” the wine in the bottle. And most Virginia wineries, especially those who have been around for a while, are focused on this niche. We are moving to clarify terms and tighten things up regarding who qualifies as a Virginia farm winery and what we can uniquely offer—though the devil is in the details, as always. The world has lots of niches, so there’s room for everyone. I expect we’ll eventually sort it all out.

In the meantime, I sincerely hope you will continue to seek out and celebrate authenticity at places like DuCard Vineyards, where we really are and remain “true to our roots.”

“Virginia Wine”…deciphering the label

What does it mean?

By Scott Elliff.

The minimum requirement for wine to be classified as made by a Virginia farm winery is that at least 51 percent of the grapes come from land owned or leased by the named winery. At many smaller and older wineries, the figure is at or near 100 percent, meaning all the grapes are farmed by the winery, mostly at on-site locations. But such purity is less common today due to new winery business models, industry growth, related shortages of grapes, and limited land on existing vineyard/winery sites.

A handful of mostly larger wineries in Virginia operate under a different classification, with their requirement being that 75% of the grapes must come from within the state, but not necessarily grown by the winery itself.

Traditionally, leased land meant off-site land that the winery farmed and controlled, but the term is sometimes is being used as a mechanism for a winery to buy the fruit from the leased property without actually farming the grapes themselves. Location of leased land and extent of involvement by the named winery is not indicated on the label, though it is sometimes included in describing the wine to customers at the tasting room.

Front Label:

A label reading Virginia or Virginia White (or Red) Wine means at least 75 percent of the grapes were grown in the Commonwealth.

A label reading Virginia or Virginia White (or Red) Wine means at least 75 percent of the grapes were grown in the Commonwealth.

A label reading American means that less than 75 percent of the grapes were grown in the Commonwealth and thus are supplemented with fruit or juice from California or elsewhere. But at least 51percent of the grapes were grown on land owned or leased by the winery.

The front label will also include the brand for the winery operating the tasting room that is selling the wine.

The specifics of who grew the grapes and made the wine are on the back label.

Back Label:

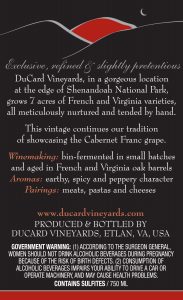

Bottled By … : This simply denotes who bottled the wine and where. This designation is typically used when the grapes were not grown by the named winery. If the town listed is where the winery is located, then the wine was made by someone else, bought as bulk wine from them, and bottled by the named winery. If the town listed is not where the winery is actually located, then both the winemaking and bottling have been contracted out to others, regardless of the brand name printed on the front.

Bottled By … : This simply denotes who bottled the wine and where. This designation is typically used when the grapes were not grown by the named winery. If the town listed is where the winery is located, then the wine was made by someone else, bought as bulk wine from them, and bottled by the named winery. If the town listed is not where the winery is actually located, then both the winemaking and bottling have been contracted out to others, regardless of the brand name printed on the front.

Produced and Bottled By … : “Produced” is the term for making the wine (i.e. fermenting and aging), and the winery name and location indicate who did it and where. This is the most common designation and represents the traditional situation where all or most of the grapes come from the winery’s property and the winemaking and bottling were done on-site. As above, if the town located is not where the winery is actually located, then the grapes probably were grown by the winery but the winemaking and bottling have been contracted out to others, and the winery has put their brand name on the finished wine.

Grown, Produced, and Bottled By … : This is the “purest” situation, and means that 100 percent of the grapes were grown by the named winery, in the town named, with winemaking and bottling done on-site.

Estate Grown: If you see this on the front label, then that means the winery is located in a designated American Viticulture Area (AVA) and nearly all the grapes were grown on the named winery’s property, in the town named. Usually this is used together with “Grown, Produced, and Bottled By” on the back label, meaning winemaking and bottling were also done on site.

The AVA name (“Monticello,” “Shenandoah Valley,” etc.) is usually included on the front of the label, and its inclusion means that virtually all of the grapes come from that AVA region. In other parts of the world and much of the U.S., designated areas are tightly defined and connote specific grapes and wine styles. In Virginia, they are broader geographic areas with more diversity of grapes,wine styles, and quality, and are to a significant degree more marketing and political designations.

Just a quick correction- The first photo is of staff member Javier Luces pouring the wine, not winemaker Julien Durantie as stated.

Thank you!I have corrected.