Two Born in the Piedmont

By Glenda C. Booth

Baseball, that great “national pastime,” is often seen as a sport that unites us all, but there was a time when unity was but a fleeting dream. In the early 20th century, African Americans were barred from playing on the major league teams, so in 1920, a group of team owners formed the Negro National League, the first successful, professional, African-American baseball league in the country.

For almost 20 years, more than 2,600 African-American and Hispanic athletes played in the league, including some legendary greats, including Jackie Robinson, Willie Mays, and Hank Aaron. The league’s players “became known for showcasing a style of speed, daring play, and showmanship,” says history.com. There were four Virginia-born players in this league: Pete Hill from Culpeper; Jud Wilson of Remington; Ray Dandridge of Richmond; and Leon Day of Alexandria.

The U.S. Senate has approved a bill, introduced by Sen. Tim Kaine (D-Va.) and Missouri Sen. Roy Blunt (R), directing the U.S. Treasury to produce a commemorative coin to recognize the Centennial of Negro Leagues Baseball. The bill says, “The story of the Negro Leagues is a story of strong-willed athletes who forged a glorious history in the midst of an inglorious era of segregation in the United States.”

Citing the four Virginia players, Kaine told The Piedmont Virginian, “At a time when African American and Hispanic players were barred from playing on major league teams, the Negro Leagues offered people the chance to see some of the country’s greatest ballplayers. I’m proud my colleagues and I worked together to ensure these players and teams are honored for their historic contributions.”

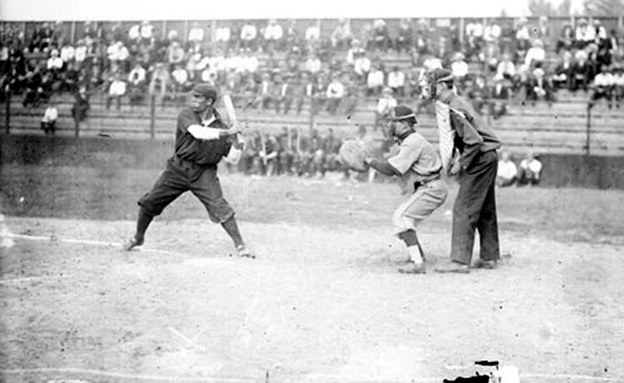

Hill batting for the Leland Giants in 1909

By Chicago Daily News – The Library of Congress-American Memory SDN-055497, Chicago Daily News negatives collection, Chicago History Museum., Public Domain

Pete Hill

Joseph Preston “Pete” Hill was born in 1882, 1883 or 1884 in Buena, near Rapidan. He emerged “from the backwoods of Culpeper County…to become one of the most feared line-drive hitters in the game,” says the National Baseball Hall of Fame website.

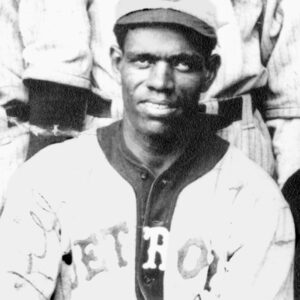

Pete Hill was born in Buena, near Rapidan, Va. His parents were probably former slaves. Head & shoulders posed portrait of newly inducted Hall of Famer, J. Preston ‘Pete’ Hill, of the Negro Leagues. Hill was one of the greatest line-drive hitters of his era. Image cropped from 1920 Detroit Stars team photo 2442.89 PD. Courtesy of National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum

Pete was the third son of Ike and Elizabeth “Lizzie” Seals Hill, both Virginians and probably former slaves, according to Orange County historian Zann Nelson. The little rural hamlet of Buena became an enclave for newly-freed slaves soon after the Civil War. Ike disappeared or may have died and Lizzie moved her three sons to Pittsburgh when Hill was a child.

A left-handed batter and center fielder, Hill played from 1899 to the mid-1920s and seldom struck out. In the batter’s box he was restless, “always in motion, jumping back and forth trying to draw a throw from the pitcher,” wrote Lawrence D. Hogan in Shades of Glory: The Negro Leagues and the Story of African-American Baseball. Hill had “a rocket arm and excellent glove,” says the National Baseball Hall of Fame website. A fast runner, Hill was once timed running the bases in 14.4 seconds.

He played for the Pittsburgh Keystones, Cuban X Giants, Philadelphia Giants, Leland Giants, and the Chicago American Giants. He went on to manage the Detroit Stars, Milwaukee Bears, and Baltimore Black Sox. Hill “helped put Negro baseball on the map,” wrote sportswriter Fay Young for the Chicago Defender in 1951.

After retiring from baseball, he moved to Buffalo, N.Y., and helped form the Buffalo Red Caps and worked as a railroad porter. He passed away in 1951. It wasn’t until 2006 that he was inducted into the National Baseball Hall of Fame.

Jud Wilson

Judson Ernest “Jud” Wilson was born in Remington in 1894 or 1899. He courted his future wife, Betty, by crossing a creek on a log to visit her, reported the Fredericksburg Star in 2001.

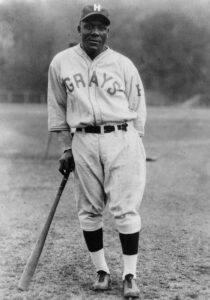

Homestead Gray player Jud Wilson

COURTESY OF NATIONAL BASEBALL HALL OF FAME AND MUSEUM

As a teenager, he moved to Washington, D.C., enlisted in the Army in 1918 and served as a corporal in World War I. After the war, he played semi-pro baseball in the city’s Foggy Bottom sandlots.

A left-handed slugger and third baseman, Wilson started his baseball career with the Baltimore Black Sox in 1922. Some sports writers called him “Babe Ruth Wilson,” but his teammates nicknamed him “Boojum” because of the booming noise of his line drives when the ball struck the outfield walls. He consistently had a high .300s batting average and topped .400 occasionally. In 1925, he went to Cuba and played for the Habana Leones, where his colleagues called him “The Bull,” for a 400-foot homerun over the right-field wall. He eventually played for the Philadelphia Stars and made the East All-Star Game several times.

Wilson also played for the Grays in Washington, contributing to six straight Negro National League championships from 1940 through 1945. A contemporary, Josh Gibson, said Wilson was the greatest hitter he had ever seen, especially hitting doubles and singles. Satchel Paige commented, “He just tried to blur that ball by you.” Wilson also became known for his fiery temper and aggressiveness during games, once lifting an umpire off the ground by the skin of his chest, but others said he had a kind heart off the field.

Wilson hoped baseball would be integrated, but in 1939 he lamented, “It’s too big a job for the people who are now trying to put it over. It will have to be a universal movement, and that will never be. . . because the big-league game, as it is now, is overrun with Southern blood. These fellows would have to stop at the same hotels, eat in the same dining rooms and sleep in the same train compartments with the colored players. There’d be trouble for sure.”

After baseball, he helped build the Whitehurst Freeway in Washington and eventually had seizures that may have been brought on by an auto accident or rough baseball plays. He was eventually institutionalized and died in 1963. In 2006, he was elected to the National Baseball Hall of Fame.

Breaking Down Barriers

Many credit the Negro National League’s players with helping dismantle segregation, for being a force for social change. Rep. Emanuel Cleaver (D-Mo.), the U.S. House of Representatives’ coin bill sponsor, said, “At a time when many were still under the erroneous assumption that African Americans were inferior to white Americans, the Negro Leagues were a proving ground that under the same rules, African Americans were every bit as good, if not better, than their counterparts in the Major Leagues.” His goal is to pass the bill by the end of the year to honor the league’s centennial. After the U.S. Treasury recoups the coins’ production costs from sales, funds will go to the National Negro Leagues Baseball Museum founded in 1990 in Kansas City, Mo.

More information

Negro Leagues Baseball Museum, nlbemuseum.com

Society for American Baseball Research, sabr.org/

National Baseball Hall of Fame, baseballhall.org/

Leave a Reply