A tour of local farms

By Pete Pazmino

Courtesy of Crowfoot Farm, by Molly Peterson

The farms of the Piedmont region offer a cornucopia of products that will please almost every palate. Vegetables, meats, poultry, dairy, fruit, fungi—you name it, we’ve got it. All of these raw culinary materials are lovingly and carefully raised by both full-time and part-time farmers—many operating small, family-owned operations—who pay particular attention to local tastes, catering to home cooks as well as professional chefs, often far beyond the regional boundaries. Searching for these products is half the fun. Driving through the region’s breathtaking vistas gives you a sense of its farm-based character that continues to thrive and make the area so special. The Piedmont’s agricultural resources are many and varied, so here’s a sampling of some of the best.

Cibola Farm

Bison, native to Virginia, are more suited to the local environment than cows.

Courtesy of Cibola Farm

Travelling five miles north on Route 522 from Culpeper will bring you to Cibola Farms, a several-hundred-acre operation that specializes in American bison. I meet Robert Ferguson, the farm’s business manager, in the freezer-filled farm store that used to be Robert’s garage. After marveling over the sheer volume of meat available—every cut of meat you’d expect from beef is available here in bison, and there’s also a surprising variety of bison sausage, hot dogs, bacon, and salami on sale—I ask how he came to raise bison in Virginia.

“I knew I wanted to farm,” Rob says. “I wanted something that was healthy to eat and healthy enough for the environment.” He explains that bison is not only more healthful than beef, since it’s much lower in fat, but that bison are actually better suited for the local environment than cows. “We hardly do anything at all,” he says. “We don’t inoculate, we don’t give them any kind of shots, we don’t handle them the same way as cattle because they’re native. They’re already acclimated. All we have to do is not screw that up.”

As Rob drives me in his Jeep through their wooded pastures, he explains that they maintain their 350 bison in three separate herds that rotate through the many pastures into which the farm is divided. And then we pass through a gate, and one of the herds is all around us. “Wow,” I say. It’s all that comes to mind. Bison are America’s largest mammal—the bulls can easily get to be well more than 2,000 pounds, and even the comparatively smaller females regularly weigh in at 1,100 pounds or more. The massive head alone looks like it could weigh several hundred pounds. Rob explains that they actually use their heads as snowplows in the winter to get down to the green grass. “We’re a grass-based system, so they’re always on green grass,” he says, then adds that they also put out a grain wagon when the herd is about to be processed. “It’s free choice. Some animals are pigging out on the grain and some animals hardly ever go to the grain.” But the grain helps improve the overall flavor and texture of the meat; since bison are already so low-fat, a 100-percent grass diet would make that even lower.

Customers interested in obtaining Cibola’s bison meat have several options. The farm store, which is open seven days a week for those who want to visit the farm and take a self-guided walking tour, sells a variety of bison leather goods—wallets, purses, iPad covers, even full hides for people who are into their own leathercrafting. Their online store is also easy to use and will ship. In addition, Cibola Farms participates in several farmer’s markets every weekend: Dupont Circle, Capitol Riverfront, Falls Church, and Arlington.

North Cove Mushrooms

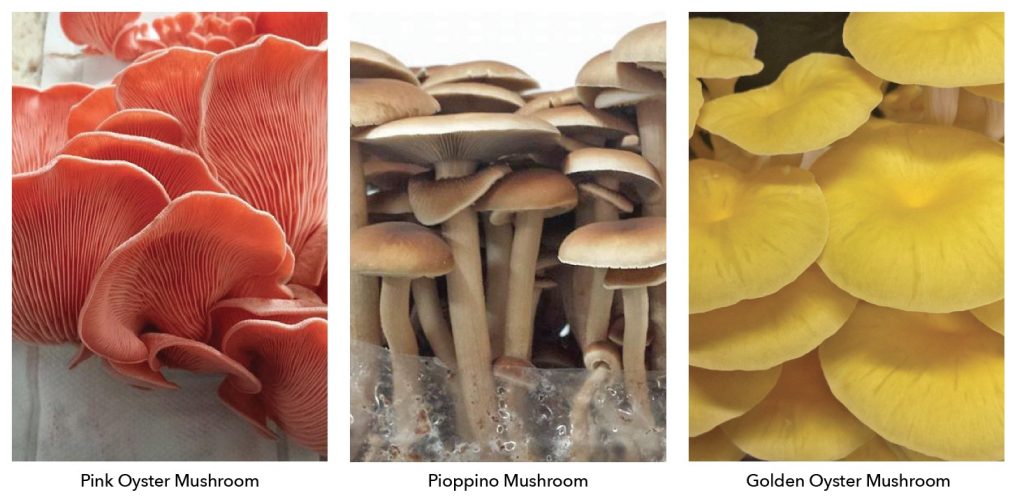

Pink Oyster Mushroom, Pioppino Mushroom, Golden Oyster Mushroom.

Courtesy of North Cove Mushrooms

Brightwood lies about 10 miles southwest of Culpeper along Route 29. There, down a very long, rutted driveway that will brutalize any low-suspension car, one will find North Cove Mushrooms, owned and operated since 2010 by Robin and Eason Serne. It’s Robin who meets me at their 10-acre facility, a compact warehouse nestled cozily among the trees. The farm specializes in growing high-quality shiitake, oyster (blue and yellow), lion’s mane, maitake, and pioppino mushrooms with an eye toward “environmental sustainability, wellness, and supporting the local economy and community.”

Robin shows me their growing room, which isn’t what I was expecting. Instead of a dank cellar, it’s a well-lit warehouse where rows of shelves are lined with cinder-block-sized bricks of compressed oak chips (for shiitakes) and bags of compressed straw (for everything else), all sprouting mushrooms. By growing their mushrooms indoors, North Cove can harvest year-round. In fact, since they pick every day, their mushrooms are always far fresher than what’s at the grocery store. It’s eco-friendly, too—the wood chips and straw, when used up, will become compost. They’ve even developed a process for eliminating competing molds on their growing blocks that uses a hydrogen peroxide solution instead of the industry-standard bleach. “It’s a ton of work and it’s more expensive,” Rachel says. “But I don’t want to eat mushrooms that have been soaked in bleach.”

Customers can buy mushrooms on the farm by appointment only. The best way to find them is at one of the seven farm markets in which they participate. In Virginia, you can find them on Saturdays at the Harrisonburg Farm Market and the Charlottesville City Market. They’ll soon be starting at Charlottesville’s Stone Field Farmer’s Market. On Sundays in D.C., they participate in the Dupont Circle and Palisades markets. Finally, in Maryland, they’re in Silver Spring on Saturday and Takoma Park on Sunday. It’s a lot of work, but their product is in demand. “We’re going to sell 400 pounds of mushrooms this weekend,” Rachel says.

In addition to the mushrooms, North Cove has just started operating a farm-to-table food truck, the North Cove Café, that features their mushrooms, meat from pasture-raised cows and chickens, and local bread and honey. You’ll find them on alternate Sundays at Culpeper’s Bald Top Brewery as well as at other local breweries and wineries. They also sell pre-packaged food, including handmade ravioli and shiitake bean burgers, and a variety of other mushroom-based products such as seasoning salt, broths, and even a coffee blended with reishi mushrooms that Rachel says will “help counteract the coffee jitters.” She’s also a champion of the mushrooms’ many medicinal qualities, and sells a variety of medicinal tinctures that she creates. “They are all immune-system boosting,” she says. “They are cancer fighting, they are anti-bacterial, anti-viral, anti-fungal.” She smiles. “I don’t get sick very often.”

Waterpenny Farm

Rachel Bynum and Eric Plaksin’s Waterpenny Farm’s on-farm stand.

Courtesy of Waterpenny Farm

Fourteen more miles north on Route 522 will land you in Sperryville. Immediately outside this charming hamlet lies Waterpenny Farm, an idyllic, 10-acre plot of land nestled alongside the Blue Ridge Mountains. It’s in the pole barn that houses Waterpenny’s self-service farm store where I meet Rachel Bynum, who with her husband, Eric Plaksin, started the farm in 2000. “We grow a fixed variety of good market vegetables,” Rachel tells me, a variety that includes squash, kale, cucumbers, and spinach. But, she adds, “We sort of specialize in tomatoes.”

The farm itself is named for the “waterpenny,” an ultra-sensitive beetle larva that has external gills and survives only in pristine water. It was on an early visit to this land that Rachel picked up a stone from the creek running through and found eight waterpennies. Having worked previously with the Chesapeake Bay Foundation, she couldn’t help but see this as a positive sign. Maintaining a balance with nature has always been one Waterpenny’s guiding principles—everything grown at the farm is free of even organic pesticides. “We call it ecologically grown,” Rachel says.

For customers wanting their vegetables, Waterpenny offers a weekly CSA (community supported agriculture), which Rachel explains is their most economical, and also eye-opening, option. “It’s for people who want to be more adventurous with their eating,” she says. “You never know what you’re going to get.” Pickups include regular newsletters that detail not only what’s happening at the farm, but also provide recipes for what’s incorporated in the pickup. Pickups are available every Thursday at the farm store, and are also made available for out-of-town customers at locations in Warrenton, Falls Church, and Arlington. Shopping at the farm store is also an option. Many local customers opt to pre-pay for their vegetables ($100 to $200 is a typical prepayment), then pick up what they want over time until their balance reaches zero. Customers can also pay as they go. For either type of shopper, though, Rachel recommends visiting the farm store on a Friday or Saturday afternoon, which is when they’re bringing in the harvest for the weekend markets.

In addition to their vegetables, the farm sells tomato soup made from their own tomatoes, honey from their beehives, and a variety of plants. They’ll also have, for the summer, 200 laying hens whose eggs will be available for purchase. Rachel stresses, though, that Waterpenny is not a year-round operation. “We like to have time to shut down in the winter,” she says. “We’re pretty barebones and simple, but I think people appreciate that.”

Bean Hollow Grassfed

Lambing season at Bean Hollow Grassfed.

Courtesy of Bean Hollow Grassfed

From Waterpenny, it’s another short hop over to Flint Hill, where just outside town you’ll find Bean Hollow Grassfed, a bucolic, 100-acre expanse of sheep pasture and woodland located on the Jordan River. The farm is owned and operated by Mike and Betsy Sands, and over a cup of coffee in their gorgeous country kitchen, Mike tells me that the farm has been in his wife’s family for about 40 years. The two of them ended up here after leaving careers in the nonprofit world. “We were here on a gorgeous weekend visiting,” he says. “And we said, God. The Rappahannock Moment, oh my God.”

Bean Hollow’s primary focus is lamb, but for Mike it’s also about stewardship. “I’ve always been particularly interested in how you use agricultural management, particularly grazing management, to actually improve the natural resource space,” he says. Then he invites me to hop on his ATV for a ride to see the flock in their current pasture. He has about 180 adult ewes, but it’s lambing season now, which means that new additions to the flock are appearing by the hour. I watch as Mike locates three newborns in the flock and, despite the bleating protestations of their mothers, gathers each up to record and label it. They lamb twice a year, he explains. The group born late last year, a smaller group of about 40, will go to market this month. This spring group, much larger, will be ready to begin processing in October.

While Mike actually sells many of his lambs to other local farmers who ultimately finish and sell the meat on their own, he offers interested customers a few options. “I do halves and wholes,” he says, a process that involves sending out a reservation flier to people who’ve expressed an interest. “How do you get on that list?” I ask him, and he grins. “Tell me.” He’s quick to caution that it’s not cheap. “I price it in two components,” he says. “The price of the animal and the butcher fees. I’m increasingly thinking it’s daunting for the client. What they want to know is, “How much am I paying for the animal, cut and wrapped and put in my freezer?’ ” So now he’s planning to also offer a “sampler box” option where consumers will be able to buy a preset weight of lamb meat, in assorted cuts, at a set price. People would pick up their boxes at the farm, just as they do with the halves and wholes.

I ask Mike if he ever sells any of the older sheep for meat, or if he only sells the lambs. He explains that it’s a generally accepted rule of thumb that lamb becomes mutton after the animal is one year old. Mutton, he tells me, is what gave lamb a bad name for years, because people often associated it with a strong, sometimes unpleasant taste. The older ewes, then, are there exclusively for breeding, not eating. “But,” he adds, grinning, “If I gave you mutton from my sheep, I don’t think you could tell it from lamb.”

Crowfoot Farm

Brown Swiss cattle are the oldest of the dairy breeds and they produce rich, creamy milk with high protein and butterfat content.

Courtesy of Crowfoot Farm; by Molly Peterson

It’s another quick drive east from Flint Hill to the village of Amissville, which is where you’ll find Crowfoot Farm, owned and operated for the past eight years by Rachel and Kevin Summers. They’re well-known for their poultry. “We are a family home site here,” Rachel tells me. “The first thing we did was poultry eggs. We still do pastured poultry. We do one batch of ducks every summer.” They also raise, for Thanksgiving, a special heritage breed of turkey, but Rachel warns that they sell out very quickly. “We start getting reservations November first.”

Crowfoot’s farm store, open Monday through Saturday from 8 a.m. to 7 p.m., is located inside their barn. The small amount of poultry and eggs they don’t commit to their CSA (information on joining that is available on their website, although they are sold out for 2017) is available for purchase there. Most of what they do is small batch, so they don’t have every kind of egg year-round, but they usually have chicken meat. They also sell a very limited supply of grass-fed beef from cows that are born and weaned here, then pastured and finished on a neighboring farm. In addition, they sell handmade soaps, which Rachel learned to make during her years at Claude Moore Colonial Farm.

For customers seeking something truly different, though, Crowfoot also allows customers to purchase ownership shares in their cowherd. These ownership shares are, in essence, a contracted arrangement with Crowfoot Farm. In exchange for an upfront fee of $100 (for one share) and an additional monthly boarding fee of $40 that covers the cost of feeding, caring for, and milking the cows, share owners receive a weekly portion (one gallon) of the fresh milk produced by the herd as well as a monthly newsletter that includes herd updates, information about dairy cow care, and recipes for making cheese at home. Share owners can also visit the farm any time to see the cows and even watch them being milked. When Rachel walks me out to see their cows, and I watch as one gives Kevin an affectionate nuzzle. “We’re getting more and more into the dairy,” Rachel tells me. “It’s becoming our main thing.” They have two milk cows now, as well as one heifer cow who will start to give milk after having her first calf in a couple of months. And there are two more heifers up and coming. “We’ll have three calves born this year,” Rachel says. “We’re growing the herd.”

Later, in an email, Kevin and Rachel expand on how they view their farm’s relationship with its shareholders. “The herd-share system is a beautiful way to connect community and farms,” they write. “We take our responsibility to our owners very seriously, and they are so wonderfully supportive of us. We are grateful to be able to work with the cows and have a family business doing something we love while offering a service to those who would like to have dairy cow ownership and enjoy fresh milk.”

Leave a Reply