“Eventually, the bus stops coming. And then what?”

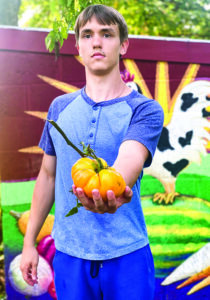

From Left to Right: Grower Matt alongside three young adults volunteering from a local church to help AFLO staff weed & harvest, Grower Jonathan with Farm Manager Kate displaying some of the day’s harvest, Crew Leader Sabrina sharing a tomato with Grower Kylie, Grower Clark displaying tomatillos & eggplants, Job Coach Meredith with Grower Miguel

Story and photos by Ed Felker

Maya Wechsler and Greg Masucci’s son, Max, is autistic and non-speaking, with serious sensory and attention challenges that require him to be with a caregiver at all times. The school system provides some programming and services for children with developmental disabilities, but parents of kids like Max spend years preparing for the day when those kids age out of those programs. Questions mount: Who will care for them while we’re at work? What will they do all day? Can they work? How would they be treated? Can they be happy?

Maya and Greg fought the school system for years in Washington, D.C., where they lived. Frustrated, angry, and burned out, they struggled to find balance in their lives. In 2014, when Max was seven, they made the monstrous leap to try to provide a simpler, safer, and happier home for their children.

“We wanted to move somewhere completely different, where we could do something positive in the way of advocacy—something that wouldn't eat us alive and leave us bitter,” Maya says. And for self-proclaimed “city people,” the move from what Maya describes as a “postage stamp” yard where she grew precisely two plants, to a 24-acre Piedmont property in rural Bluemont was unquestionably completely different.

Grower Yegor carefully displaying a ginormous tomato he had a hand in raising

“We went from hearing ambulance sirens and conversations beneath our window each night to total and utter silence,” Maya says. “The darkness was probably the most shocking thing about it—the utter lack of anything but stars.” They now had the land, but lacked a real plan for how to use it. Shortly after closing on that property, the couple sat in a Thai restaurant on their way to a weekend away in Shepherdstown, W.Va. It was there, as Greg likes to put it, that they “hatched a plan on the back of a napkin.”

“We decided that plenty of parents were doing battle with schools,” Maya says. “Perhaps we could do something more positive by training people for employment.” The idea was to use the land they were already paying for rather than investing in a separate business.

But plants, vines, and grass grow aggressively in rural Virginia, and they quickly learned that land wasn’t easily tamed. They would need the proper tools to fight that battle. They talked with other farmers and people experienced in agriculture. “We eventually figured out what ‘bush-hogging’ was, and that we would need a better chainsaw and waders to battle the weeds in our ponds,” Maya said.

She took classes through the Virginia Extension Department and read books on how to farm. She joined twilight farm tours. “If you have enough land to play around on, and throw some seeds into it, eventually something will grow,” Maya says. “So I spent a year learning how to grow stuff. As for Greg, he's been handy ever since I've known him, and what he can't figure out on his own, he talks to other people for advice, or turns to YouTube,” Maya says.

Crew Leader Sabrina contemplating the next task for Growers

So Greg was well positioned to be the "Engineer" in their venture. Together they learned, and built, and farmed, and by 2015, Maya managed to grow more vegetables than she could possibly give away.

Somewhere along the way, they decided they were building something long-lasting, that went beyond their family—a place where Max and other adults with intellectual and developmental disabilities (ID/DD) could find paid work, acceptance, and meaning. They launched A Farm Less Ordinary (AFLO) in the spring of 2016. During that first growing season, as a 501(c)3 non-profit organization, they hired five ID/DD adults from around the area. While these employees, or “Growers” learn how to farm, they also are taught valuable life and employment skills.

AFLO teaches their Growers self-advocacy skills like asking for help or telling their coworker or manager when they need a break. The Growers are taught how to get along well with coworkers, which includes speaking about appropriate topics, acknowledging people, and respecting other people's personal boundaries. They learn to remain calm when taking on a new challenge, to work through sub-optimal conditions to complete a task, and to finish up their assigned work even if they’re having an emotional day.

Grower Jonathan in the field making sure tomato plants get some TLC

As in any other enterprise, employees have different strengths. Farm Manager Kate McDowell, who joined the AFLO team in 2020, loves to figure out what all the Growers are good at and let them lead that task.

“Frankie is a social person, so he has been asked to welcome new volunteers. Brad loves machines, so I taught him how to use the zero turn mower. Turns out Shane loves to sort things, so he is really good at sorting out the green or broken potatoes,” she says. “It's really fun and rewarding seeing everyone take ownership of their part on the farm.”

AFLO’s operating revenue comes mainly from grants and donations. “We have some loyal donors who donate on a monthly basis,” Maya said. “We also receive donations throughout the year and during participation in 24-hour fundraising events, such as Give Choose or Giving Tuesday.” The farm also sells vegetables and other agricultural products through a Community Supported Agriculture (CSA) program, at farmers markets, and to local restaurants.

Lynne Wright met Maya and Greg at the Leesburg Flower and Garden show in the spring of 2019. She had formerly run a flower and herb business from her property in Leesburg and was hoping to find a good use for the greenhouse that was no longer being used. Lynne and her husband, Michael, loved AFLO’s mission, and allowed the use of their greenhouse and part of their land. The Wright’s Leesburg farm would be the first time Maya and Greg would be running a farm operation away from their residence, which presented another learning curve to tackle.

Co-Founder & Chief Operating Officer Greg Masucci, sharing with staff & visitors during a ribbon cutting ceremony in June 2021 the importance of adults with developmental disabilities to have employment opportunities where they can be contributing members of society & earn their own paycheck.

It would also be the first Loudoun County farm, which presented some new opportunities. “We were excited about the coming year and how much easier it would be for us to access the special needs classrooms in Loudoun County Public Schools and the volunteer base we knew was waiting for us in Loudoun,” Maya says. “And then…Covid.”

Farming, though, was considered an essential activity in 2020. Additionally, the work was taking place mainly outdoors. “We actually survived that crazy year with an even bigger employee and volunteer base than we could have hoped for during a pandemic,” Maya says.

Schools were closed and many other training and employment opportunities were put on hold that year, but the need for young adults with ID/DD to find ways to connect and learn remained. “People were desperate to get out of their homes and do something useful with their hands,” Maya says. “So we were able to welcome a ton of volunteers to the farm in Leesburg.”

But AFLO’s agreement with the Wrights is limited, as they are not sure how long they will live on that land. And the farm at the original Bluemont property needed to move, as Maya, Greg, and their family set their sights on moving their family a bit further east. Six years in the Bluemont area, with more limited access to services and longer commutes for caregivers proved taxing. “I put something on AFLO's website, with the blind hope that someone might notice it,” Maya says. “I wrote something vague like ‘if you know someone with land in Loudoun County, contact us.’” She didn’t think anything would come of it.

John and Katey Driessnack of Lovettsville became aware of AFLO when an old friend reached out to Katey to ask her opinion on an employment program she was looking at for her 28-year-old son who lives with Autism. The friend sent Katey the link to AFLO’s website, where she read of the search for a site to relocate the original Bluemont site. The wheels immediately started turning.

“John and I have spent the last 38 years working and volunteering in capacities that serve others—our nation, juvenile offenders, foster children, people living with mental illness, church youth groups, and scouting,” Katey says. “So this request was intriguing.” Empty nesters with grown children, they had land and a barn that John built. Katey was retired, and John was working from home.

“Here we were with these great resources—time, space, land,” she says. They wanted to do something with those resources that was meaningful for others. “Our parents taught us that every person has value. Our religious faith taught us that every person has gifts to share.”

Grower Clark always ready to meet & greet visitors

After thoughtful discussion with family members and each other, they reached out to Maya and Greg to explore the idea. Greg, Maya, John, and Katey spent the better part of 2020 figuring out details, and AFLO’s operation began moving to the Driessnack’s Lovettsville property last September.

Fencing went up, thanks to the help of numerous volunteers, and the fields were prepped. In November, 60 blueberry and 60 raspberry bushes went into the ground, and in December the greenhouse was moved from Bluemont and re-erected. Things were shaping up nicely at the Driessnack’s, but when they saw what had gone into AFLO’s operations at the original location they knew that storage space, a cooling room, and a place to wash vegetables were all needed.

“Katey and I decided if we were going to do this, we should do it right,” John says. He designed a 32’-by-48’ pole barn with ample electricity run to it. The barn would house two cool rooms, a washing station, and room to store equipment. Much of the timber used to frame the barn came from the property. Large ash trees that had died from the Emerald Ash Borer beetle were cut down and milled with the help of neighbor Steve Maurer.

The barn was built with the help of Mormon Elders. Due to Covid, the Elders were not allowed to do their normal visits, so they volunteered to help AFLO construct the barn. “This turned out to be a great synergistic relationship” John says. “Crews of Elders, 20-or-so-year-old young men and at times Sisters (20-year-old-women) showed up in four-hour shifts, one or two groups with two or three in each group.”

A Farm Less Ordinary started with a need identified, a desire to help, and a vision of how to do it all. But it took and continues to take countless volunteer hours, hard work, materials, seeds, teachers, donors, patience, passion, and time.

After all the work and weather and worry, when Growers finally stand at a vine or lean down to a plant in the earth, and they use what they’ve learned to choose the tool and identify which plants to harvest, it all comes together. And that beautiful tomato, pepper, head of lettuce, or any other vegetable in their hand is fresh. It’s plentiful. It’s delicious. And it’s far from ordinary.

Leave a Reply