Illustrating the Northern Piedmont’s Past and Present

Story and photos by Kaitlin Hill, all maps reprinted with permission of Eugene Scheel

When asked to define himself, Eugene Scheel of Waterford jokes, “When I want to impress people, I say I am a historian in private practice. If I don’t need to impress, I say I do odd jobs in the field of history.”

So much more than odd jobs.

Eugene Scheel

Scheel has worked as Northern Piedmont’s premier mapmaker and historian for 50 years, creating nearly 100 meticulously hand-drawn maps and authoring a series of books detailing local history. And, he is showing no signs of slowing down. With multiple projects running simultaneously, requests for updated editions, and a contagious curiosity to keep him going, Scheel is still in the field, putting pencil to paper and preserving Virginia’s unique history as only he can.

Born in the Bronx during World War II, Scheel describes his earliest endeavors into mapmaking as “doodles.”

“I grew up in a time where maps were featured in every publication because of the Second World War. I got used to seeing these hand-drawn maps.” He continues, “I was a youngster, I doodled imaginary countries and islands and aerial views. I just doodled my own little maps instead of other types of doodles,” he says.

His childhood inclination toward cartography inspired him to connect with Gilbert Grosvenor, then editor of National Geographic Magazine and president of the National Geographic Society. Scheel remembers, “When I was in high school I wrote to Gilbert Grosvenor and said, ‘I like to make maps. Where would you recommend going to college?’”

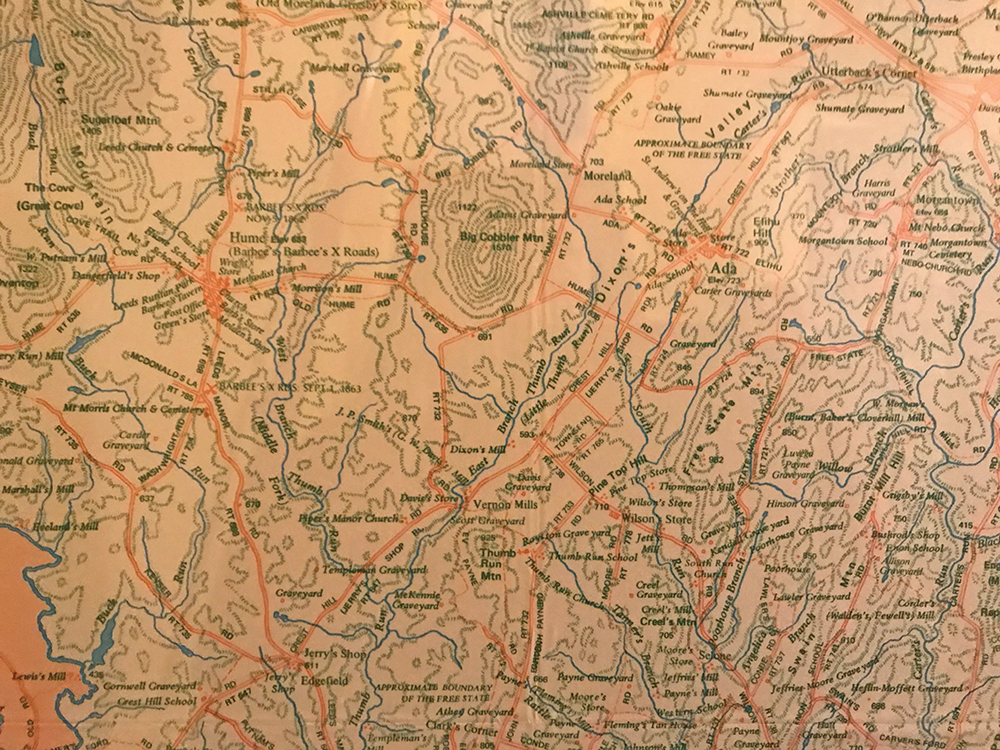

Detail of Scheel’s Fauquier County map (1973) showing the Big Cobbler Mountain area of northwest Fauquier County.

Scheel followed Grosvenor’s recommendation to attend Clark University, a small school in New England, where he would earn an A.B. in Geography.

After graduation, Scheel served as a Marine and took “a couple of quick odd jobs” before reconnecting with Grosvenor and deciding he might like to work for him. Scheel says, “I decided to work for National Geographic Magazine. They make nice maps. So, I wrote [Grosvenor] again and said, ‘I followed your advice and I went to Clark University, where I did very well.’”

Scheel was invited for an interview and joined the staff at 17th and M Street, NW, in Washington, D.C., in 1960.

“My job at National Geographic was to read manuscripts that went in the magazine and suggest ideas for anything that wasn’t photographic, in other words, artwork, maps, diagrams. At the time we were doing a lot of work, consider the space program and undersea work, and these were subjects that couldn’t be covered at the time. We’re talking mid-60s.”

In 1965, Scheel and his wife moved to Waterford, back then a 55-minute commute to downtown Washington. In 1968, Scheel notes, “The job became somewhat of a sinecure. So I decided to leave National Geographic and go out on my own.”

He moved his office and his focus to Virginia. “I was a consultant for the governor’s (of Virginia) office under Linwood Holton. I think he came in ’71. I did a lot of little different things,” Scheel recalls. He adds, “Then there was an advertisement in the Loudoun Times Mirror for somebody to draw a map of Loudoun County.”

Scheel took on the project and added his own flair. He explains, “In 1970, ‘71 there weren’t any really good maps, just a little highway map. So, I decided to make it somewhat of a historical map because I was interested in history. I started adding mills and old schools and everything like that.”

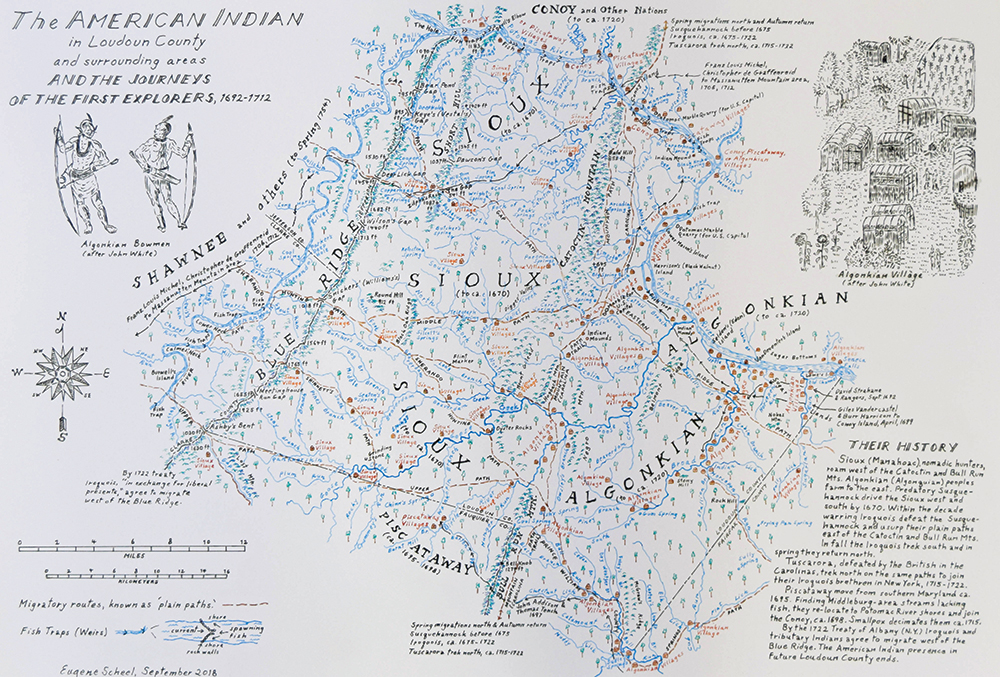

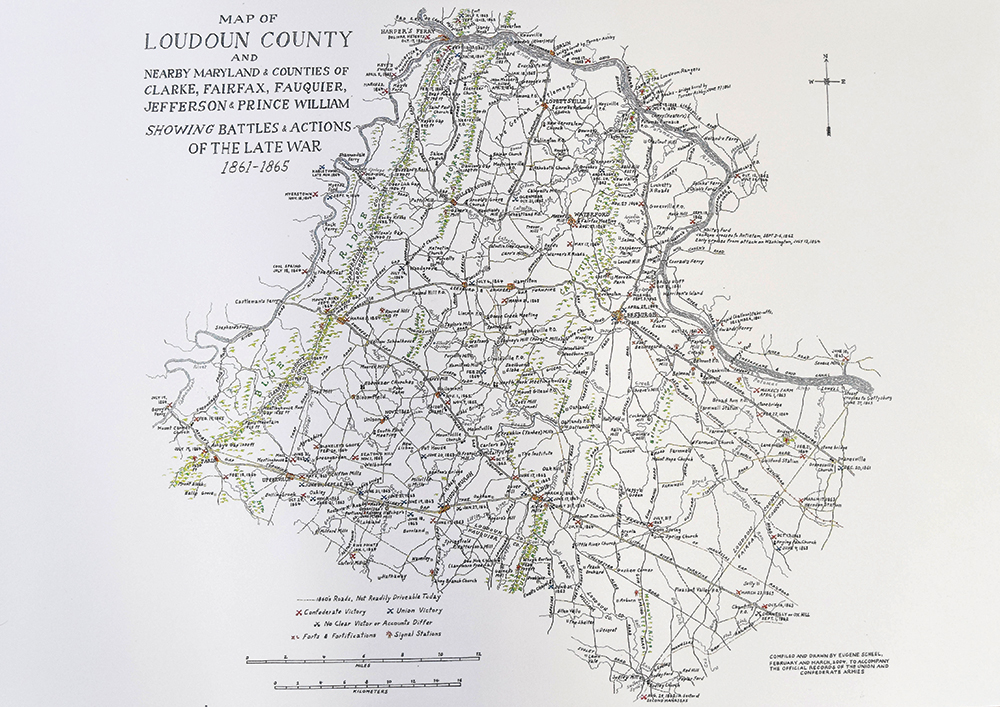

His Loudoun County map was published in 1972 and its success led to more mapmaking opportunities. In subsequent years, he would illustrate Fauquier, Culpeper, Madison, Prince William, Clarke, and Rappahannock counties, as well as more specific info-graphics capturing the Civil War in Loudoun County, an American Indian map of Loudoun County, and his Prince William: African-American Heritage Map detailing historic Black churches.

He even did a special rendering of Atoka Farm outside Middleburg for Elizabeth Taylor to gift then-husband Sen. John Warner (R-Va.), and a detailed depiction of the Bermuda Islands that was presented to the Queen of England by the Government of Bermuda.

While mapping out his own path, Scheel picked up two additional degrees: a graduate degree from the University of Virginia’s School of Architecture and a graduate degree in American Literature from Georgetown University.

According to Scheel, his style of mapmaking is 30 percent drawing and 70 percent research, which relies heavily on those he refers to as “old-timers.” Of his process he says, “It entails going around in all terrain vehicles and speaking to a lot of old-timers…I try to find somebody who is familiar with where they went to a one-room school and they’ll know everything within a two mile radius. And they’ll then suggest I go talk to so-and-so and so-and-so…I ask, ‘What’s the name of that hill?’ ‘What do you call that field?’ ‘Is there anything unusual about that river?’ So I ask a myriad of questions and put together a map that way.”

With a wealth of area information collected, Scheel can put pen to paper. He explains, “My earlier maps were mostly freehand but in regard to the type, that was machine set and I had to laboriously put it on.” He continues with a chuckle, “Then I decided that my handwriting was fairly decent and so I’ll do the hand lettering. Now it’s all freehand.”

Maps are intricately inked on a “stable-base plastic that doesn’t lose its shape,” Scheel explains. He adds, “I draw in ink or pencil, nothing unusual.” And the entire process of deep research and detailed drawing takes two to four years, depending on the map. In total, Scheel believes he has completed roughly 70 maps, the majority of them large scale.

Not only an accomplished mapmaker, Scheel has also authored a small bookcase of local historical studies and newspaper columns. He shares, “In 1976, with the bicentennial, I proposed to the Loudoun Times Mirror that I would do a series on the history of the 120 communities, villages, and towns that used to make up Loudoun County. I just started alphabetically and finished after about three or four years.” In 2002, The Thomas Balch Library in Leesburg turned his Loudoun County writings into a series of five volumes called, Loudoun Discovered – Communities, Corners, and Crossroads. The series is 900 pages in total.

And from 1999 to 2010 he wrote a history column for local editions of The Washington Post.

Even with too many accomplishments to count, Scheel is still working. Currently, he is finishing a history of agriculture in Loudon County based on the minutes of the Catoctin Farmers’ Club, the 100th Anniversary of St. Francis de Sales Catholic Church in Purcellville, and a large series of farm maps out of Clarke County. Some of his earlier maps are in the process of being reprinted, too. Scheel notes that Laura Kelsey of the Fauquier Historical Society is in the process of having his Fauquier map updated and reprinted with a partial grant provided by the Fauquier Bank.

When asked how he picks his projects, he jests, “Whatever I get paid for.”

But more than pay, it is obvious that passion is what keeps Scheel going. “I enjoy doing what I’m doing and as long as my mind, my hands, and my eyes are fine, I will go on doing it.”

Leave a Reply