By Carla Vergot

Let’s talk about bugs.

Next to my husband’s over-planting every bed, the bugs are what bother me most. Ricky’s biggest annoyances are my planting seedlings too far apart (i.e., adhering to the recommended spacing on the seed packet) and squirrels. But let’s get back to the bugs.

I’ll be the first to admit, the animal lover in me extends to all creatures. You can imagine that the bugs, who decimate our vegetables, put me in a real pickle here. This has always been an issue for me, and not just in my garden. (You can almost feel an anecdote coming on, can’t you?)

When I taught elementary school in Fairfax County, I was occasionally in the grade that took advantage of a field trip to Jamestown. The volunteers out there did an exceptional job aligning their curriculum to the standards of learning, and the students always got a lot out of it.

One year, I was corralling a small group of kids to the area where the docent talked about how children their age would have had the important job of picking bugs off the tobacco plants and smashing them so the insects wouldn’t destroy the valuable crop. She proceeded to show us how to do it, then she invited us each to find and kill a bug.

Now, being a teacher and a gardener, I truly appreciated this up-close and personal approach to learning—kids in a garden, getting their hands dirty. However, it occurred to me quite suddenly that I hadn’t built a foundation for this experience in advance—the difference between pests vs. beneficial insects, and why we were killing bugs to protect tobacco which we all knew was dangerous. These same kids had heard me talk about not harming living things and seen me relocate spiders from our classroom to the great outdoors because I refused to let them be killed. And here we were about to smash bugs at Jamestown. Talk about your mixed messages.

I pulled the plug on the learning experience, explaining to the docent that while it was important that my students know what their jobs would have been in Colonial times, I had not given them the background information that would allow them to synthesize it properly. To Jamestown’s surprise, my group abstained.

I think about that day periodically during the summer growing season when I encounter what seems like hundreds of the dreaded squash beetles accosting our trombone zucchinis and Armenian cucumbers. They are prolific, and they pair up and woo each other in a massive orgy, doing their little dance, leaving a trail of destruction.

So, I smash them. I catch them, sometimes two together, and I pinch them between my thumb and forefinger, dozens at a stretch until my fingernails are stained yellow from their bug guts. I know this all comes down to a them-or-me situation, and they will, without a fleck of guilt, damage our vines. In spite of that, I still have a tug of remorse every time I feel the crunch of an exoskeleton.

I know this is one of the reasons people resort to chemicals to control pests in lawns and gardens. But with both methods, mechanical and chemical, you’re still killing something. When you pluck it and smash it, though, it becomes very real and even a little distasteful. When you employ the chemical spray, you’ve basically hired a hit man to do your dirty work. Sure, you paid the price, but you can convince yourself that there’s no blood on your hands. Once in that state of denial, it’s also very easy to ignore what the chemicals are doing to your body and the environment.

Managing the bugs without chemicals is just one part of the tricky love-hate relationship Ricky and I have with squash. We love them for many reasons. First, the seeds are so willing they can be directly sown in the dirt. They don’t need to be started indoors months earlier, in fact, they laugh at you for wasting your time. When they germinate, they burst from the ground with a vigorous fanfare that’s such a pleasure to watch. They remind me of the relentless Kudzoo that some people claim grows a foot a day down North Carolina way. Our squashzoo comes in a close second.

Their leaves are broad and lush, developing into extravagant bushes or vining over an archway Ricky built from a section of cow fence. Under the arch in mid-summer is a sweet shady place. The dark yellow blossoms are dramatic, and if you take the trouble to prepare them, delicious. The deep throats of the blooms amplify the buzzing of bees who play there and emerge dusty with pollen.

And let’s not forget about the fact that the squash are prolific producers. We scaled back our trombone zucchini crop this year, because four plants produced way more than we could eat and give away. Friends pointedly requested no more gifts, so I had to catch the mailman and surprise random delivery drivers on our street in order to pass out the surplus.

Once harvested, squash also lasts a long time if stored correctly. We ate our squash all winter long, and we didn’t even pretend to know how to store it. We just piled it up in the trays of the grow light and grabbed the next one when it was dinnertime.

The hate part of the relationship is really limited to the bugs. They don’t seem to respond to the diatomaceous earth, a technique that has proven highly successful in keeping pests off other plants. In fact, I’m beginning to think that the dust is more like an aphrodisiac for these clowns.

It’s my understanding that the bugs don’t actually kill the plants, but they damage them to the point where disease will invade. It can wipe out a thriving, vibrant squash plant overnight. We lost a black beauty zucchini in an afternoon one year, having received only two of what promised to be dozens of the gorgeous fruits.

When I’m in bug-smashing mode, I usually whisper a quiet, “Sorry,” to the tiny critters. And while it never crosses Ricky’s mind again, I do consider their little ghosts every time I grate a trombone zucchini to make squash cakes in the cast iron skillet.

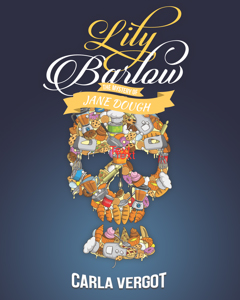

We are excited to announce that our longtime columnist Carla Vergot is publishing her first book, Lily Barlow: The Mystery of Jane Dough.

Lily Barlow, a quirky college student obsessed with the fictional bounty hunter Stephanie Plum, is called home from UVA to get the family bakery running after her dad’s heart attack. To maintain her independence, she rents an apartment from Miss Delphine, a spunky old woman Lily believes may be covering up a crime. Meanwhile, Lily recognizes a murder victim on a website. Oh, and Jack Turner, her best friend since kindergarten, picks now to tell her he wants to take their relationship in a different direction.

Lily Barlow, a quirky college student obsessed with the fictional bounty hunter Stephanie Plum, is called home from UVA to get the family bakery running after her dad’s heart attack. To maintain her independence, she rents an apartment from Miss Delphine, a spunky old woman Lily believes may be covering up a crime. Meanwhile, Lily recognizes a murder victim on a website. Oh, and Jack Turner, her best friend since kindergarten, picks now to tell her he wants to take their relationship in a different direction.

Lily Barlow: The Mystery of Jane Dough will be available in bookstores and on Amazon.com on December 4. Meet Carla at her book signings on December 8 at Second Chapter Books in Middleburg, or December 9 at the Four Seasons Bookstore in Shepherdstown, WV. Books must be purchased at the book signings.

Leave a Reply