Fighting Words From “Gettysburg” Film Director and Rappahannock County Resident

Guest Essay by Ronald F. Maxwell

“To experience the full imaginative appeal of the Civil War,” says Robert Penn Warren, “…may be, in fact, the very ritual of being American.”

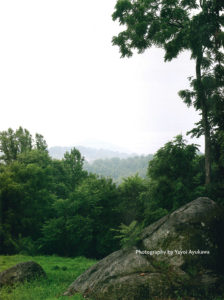

To begin to experience this imaginative appeal we need more than books and movies. We need, as those who stood their ground 140 years ago knew all too well — the land — the untamed, unmolested, undefiled land. Not just the battlefields, but the open spaces and the old places that all humans need. Would Jackson recognize Manassas Junction? Would Lee know how to find Fairfax Courthouse?

Of course, we live in different times. We live in a world in which major decisions about the quality of life — and indeed the meaning of life — have been funneled into a narrow economic equation of worker and consumer. In such a world the natural curves and undulations of nature are in the way. They are an impediment to the dominant concern of the bottom line: a headlong pursuit often-times conducted with a myopic obsession blind to the concerns of others or to the impact on any other aspect of human or natural life.

Of course, we live in different times. We live in a world in which major decisions about the quality of life — and indeed the meaning of life — have been funneled into a narrow economic equation of worker and consumer. In such a world the natural curves and undulations of nature are in the way. They are an impediment to the dominant concern of the bottom line: a headlong pursuit often-times conducted with a myopic obsession blind to the concerns of others or to the impact on any other aspect of human or natural life.

In such a world, hills must be flattened, rivers must be tamed, roads must be straightened, all natural rhythms of life must be discarded for the non-stop hyper-speed of commerce. Like a freshly washed sheet, the Blue Ridge, Piedmont, and Tidewater of Old Virginia must be shaken out, dried, pressed, and prepared for cutting and fitting. A massive alteration for the brave new world where unbridled development is king and all other considerations must yield.

But it is churlish to complain. After all, we have turned a shabby, sleepy, backward place into a thriving megalopolis of jobs and commerce and profit. To borrow an old Soviet slogan, a worker’s paradise! We have stripped away the top-soil of quaintness and tradition, we have mauled away the useless village green, we have strip-malled yesterday, with all its memories and values, entombed that old world in concrete and asphalt, never to be seen again. Never even to be remembered. For what profit is there in remembering when such a bold new future awaits?

My home is in Virginia’s Piedmont: always contested land. The first Americans fought over it amongst themselves. The English colonists took it from the Rappahannocks and the Patowmacks and the Susquehannas.

But not without a fight. Many a settler born in Ireland or Scotland lost his scalp on the Virginia frontier. In the 18th Century the French tried to cordon in the burgeoning English colonies with a string of forts from the St. Lawrence to the Gulf of Mexico. Western Virginia and Pennsylvania were the front line in a global war between France and England for control of the North American continent.

A generation later the Piedmont was a crossroads for revolutionary ideas and revolutionary actions as a new nation was conceived and defended. The land was always contested, always fought for, never cheaply won. Four score and seven years passed and a mighty whirlwind engulfed the very same place, as the armies in blue and gray swept like a great metal scythe, leaving wide swaths of blood destruction, death, and despair.

Great heroes arose, great feats of daring and courage and sacrifice were enacted in every corner and cranny of the Piedmont. A generation of Americans wept and buried their kith and kin in every town, every hamlet, every village, every churchyard. No, the land we never meekly defended or easily won.

The land is the people and the people are the land. Over centuries the love of the people has dripped its life force into the soil, into the very rocks and rivers. It is American land. It is our land.

The living are inheritors of the promises and sacrifices of the dead. We are the trustees of the their inheritance. We are duty bound and honor bound: bound by the blood and the trust of our ancestors to protest and defend the land.

We bear a great responsibility to give the next generation — and to generations yet unborn — the same beautiful, natural, historic and, yes, even sacred place that we have inherited from our beloved fathers and mothers. And the fathers and mothers who lived centuries before.

In some distant time those who occupy this place will look back upon us the way we look back. Will they say of us that we protested the land, that we cherished it — that we defended it from greed and rapaciousness? Or will they say we were cowards, or that we were simply pragmatic? Will they say we just had no choice?

In this future place, will someone looking down from the Shenandoah National Park’s Skyline Drive see an endless sea of rooftops, multi-laned roadways, warehouses, shopping malls, townhouses, traffic lights, intersections, water towers, signal towers, cellphone towers, just for the hell-of-it towers? Will the sound of birds and leaves rustling in a breeze be buried in the incessant din of sirens and horns and engines and traffic and machines and aircraft? Will the very last meandering two-lane country road vanish from the earth, straightened and flattened and widened and improved?

This time the conquering armies will not come in Red Coats or Blue Coats or Gray Coats. They will come disguised as friendly businessmen, as concerned neighbors, as disinterested politicians, as champions of free enterprise, as defenders of property rights, as professional planners, as the high priests of those who know what’s best for us — they will pose as our very best friends.

Plans are afoot by the bureaucrats who spend our taxes to build an Outer Beltway circling the Nation’s Capital. This 8-to-10-lane behemoth would crash right through the heart of the cradle of American history and pave over some of its most scenic areas. Even before the first SUV rolled over the new Beltway, the road would already be obsolete, but not before spawning its seed: thousands of mini-malls, gas-station complexes, fast-food troughs, outlet hangars and row houses. Their very names mock us by reminding us of what used to be: Battlefield Park; Piedmont Outlet; Monticello Overlook; Stonewall Mall; Lee Leisure Village; Mosby Motor Park; Thoroughfare Gap Estates; Clevinger’s Corner.

The Piedmont — so precious, so unique, so splendid in its particularity and distinctiveness — would be reduced to everywhere America, the same monotonous no-where. Every places looks the same, everyone shops in the same stores, eats the same food in the same plastic shacks, breathes the same polluted air stuck in the same congested traffic. Small entrepreneurs, mom and pop businesses and long-established grocery stores and restaurants are replaced by franchises, absentee landlords and national chains. The self-employed small businessman metamorphoses into ubiquitous employee.

Have we forgotten that the liberty of this country was founded on the bedrock of self-sustaining farmers, small businessmen, and entrepreneurs — by people who owned their land and their means of livelihood? What happens to liberty when an entire population becomes employees of this or that multinational corporation with little or no allegiance to this country or any country?

Millions of dollars of revenue and profits and sucked out of the local economy and whisked away to corporate headquarters in faraway cities and faraway countries. Our farmland is paved over to make room for mega-store number 505 or 676 — to make room for more parking lots. The decision to do so is made worlds away. Our so-called representatives looks the other way or, worse, call it progress and job creation. They cut fancy ribbons in public while out of view their cohorts cut our forests.

We must not deceived and we must not be afraid. The minutemen of Concord and Lexington understood the necessity of controlling their own lives and their own land. They gathered in the village green (what a quaint notion) and stood their ground. Unlike that generation of steel and guts we are not called upon to bear arms in the defense of our land. We fight by non-violent, legally sanctioned means.

But like that generation, we are called upon to show character and courage, to be steadfast and forthright and fearless in the fight. And like that generation, we are confronted by mighty power — distant, aloof, well organized, well financed, and determined to crush all resistance.

That generation faced a despotic king and an unresponsive parliament. Ours faces the Improver and his allies. The Improver can always be counted on to justify his depredations. These justifications gobble up the English language. He improves, he develops, he creates. It is inevitable we are told. It is progress. Let’s begin by reclaiming our language. Plunder by any other name is still plunder. It not progress.

There is one word and one philosophy in particular that has been hijacked. And that world is conservative. Its root is “to conserve.” To conserve what is tried and true and good and of value. To conserve what is cherished and hallowed. To conserve what is beautiful and sacred in the heart of man and the eye of God.

Edmund Burke, one of the great men in the philosophical founding of conservatism, understood the bedrock importance of community and of social responsibility to one’s neighbors. Are we more than simply islands of greed, more complex selves than isolated than isolated personal profit centers? Might our humanness require us to be connected and interconnected?

Imagine the consequences of striding into a centuries-old community to tear up its landscape without any regard for what the residents want. When a so-called developer moves his heavy equipment across Chancellorsville Battlefield, can he not see that he is moving it across the flesh and blood of his fellow citizens? That he is maiming their psyches and damaging their souls. That he is cutting off the memory of the young from the experience of the old? That he is depriving the unborn from the knowledge and solace of their ancestors? Is this a casual offense that can be fluffed off simply with the right-to-make-a-buck excuse?

Burke, political philosopher, member of Parliament and friend to the American patriots of 1776, penned these words: “Society is an open-ended partnership between generations. The dead and the unborn are as much members of society as the living. To dishonor the dead is to reject the relation on which society is built — the relation of obligation between generations. Those who have lost respect for the dead have ceased to be trustees of their inheritance. Inevitable therefore, they lose the sense of obligation to future generations. The web of obligations shrinks to the present tense.”

So this is not a left-right issue. This is not a Republican-versus-Democrat issue. We must be careful not to let the dividers divide us, whether they be hired legal hacks, journalistic axe-grinders, or grandstanding politicians. This is our common issue and we must care about it together.

Since time immemorial man has lived in the midst of wildlife and domesticated animals. To be sure, as a species he had done much harm to that wildlife. But until recent times, most people could relate to Aesop’s fables in more than abstract ways. Nowadays, due to the expansion of the megalopolis, many people can live our entire lives without encountering a wild animal or even a farm animal — except of course on Cable TV.

But for those who worship at the altars of concrete and asphalt, non consuming animals are nuisances and pests to be moved away or exterminated. As habitat disappears, the wild creatures are pushed back into the only spaces left — national parks and forests. God instructed Noah, in no uncertain terms, to save all the animals from the flood. Now they perish at a flood tide of our own making.

A few people still work the land. A few still see their children in the daylight hours. A few still know the sight of a red fox or a blue heron. A few still feel connected to the land and to the generations that worked the land and defended it in times gone by. They are unimpressed with the pictchman’s statistic and do not understand why anyone in his right mind would boast about being the fastest growing community in America. They don’t think noise is normal, that congestion is congenial, or that McMansions are McMarvelous. And they don’t think it quaint or old-fashioned to remember and to commemorate what happened at this churchyard, at this river-crossing, or at that battlefield. As long as it is more profitable to destroy the land than to preserve it, the outlook is grim. People of good will can slow this process, but it will not be reversed unless financial incentives are put in place that mitigate bothe the pressures on open space owners to sell out to developers and the pressures on families to keep moving to someplace else.

People quick to advocate letting the marketplace take care of itself mistake the case. The marketplace has been twisted and manipulated by government for decades. Is is the government, federal and state, that has built the roads and infrastructure encouraging the creation of the megalopolis — underwriting the destruction of open space and small-town America.

It is the government that in effect subsidizes the real estate developer and the highway builder at the expense of the taxpayer. And it is the government and its elected officials who must rusk the wrath and and retribution of this well-entrenched lobby. Down come the historic buildings. Bucolic fields become parking lots. Orchards are plowed under. Folks who want to farm are moved out — while the citizens whose land is expropriated get to pay for the new roads and the new traffic lights, the sewers and concrete ramps that increasingly hem them in. Until they too want to leave. And soon, no one is left with any connection to the land that was.

Even the newcomers don’t want to stay for long — and regard those soulless places as temporary way stations to somewhere else. In our wanton and reckless destruction of everything old and quaint and small, we are well on our way to creating a temporary society where nothing is permanent and nothing is worth preserving.

Jackson and Lee and the men they led, together with their worthy adversaries, do not exist disembodied to be retrieved for our amusement or contempt when we are in the mood for being entertained or using them as political punching bags. They exist in the land. Their life is in its soil and its wind. Their names are marked by stones in a thousand fields. They exist forever in our hearts. They are more lasting than concrete. They are who we are. This isn’t about saving an old building here and erecting an antique cannon there. This isn’t about looking back or looking away. It’s about looking in the mirror of our lives and asking ourselves whether we, like those brave boys of the Stonewall Brigade, will protect and defend the land that is ours.

About the Author:

Ron Maxwell, who lives in Rappahannock County, is a film director, perhaps best known for “Gettysburg” and his latest production “Copperhead.”

Ron Maxwell, who lives in Rappahannock County, is a film director, perhaps best known for “Gettysburg” and his latest production “Copperhead.”

Leave a Reply