By Celia Vuocolo, Wildlife Habitat & Stewardship Specialist, Piedmont Environmental Council

We know its names: puma, panther, cougar, mountain lion. Felis concolor goes by many aliases, but it is best known as North America’s largest wild cat. A formidable ambush predator, cougars can grow to be eight feet long, weighing in at 140 pounds. A subspecies of this cat, the eastern cougar, once called Virginia home. However, according to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS), the eastern cougar was likely extirpated from the East Coast by 1900. The last reported harvesting of a cougar was in Washington County in 1882. The species remains a hot topic amongst Virginia residents who challenge both state and federal agencies’ assertions that the big cat is truly gone from our neck of the woods.

While Felis concolor is the general species name for the cougar, there are 15 subspecies found in North America. Recent genetic research has suggested that there is likely only one sub-species, but until a more thorough analysis can be completed, USFWS continues to recognize all 15 sub-species. The eastern cougar, or Felis concolor couguar, historically inhabited the eastern part of the U.S., ranging from Canada to South Carolina. Like the rest of its species, it was aggressively hunted by American colonists who perceived the cat as a danger to people and livestock. Bounties on the cougar were offered by state governments, and the forested habitat that this species relied on was cleared for agriculture. In 2011, the USFWS declared the eastern cougar subspecies extinct.

Although the last confirmed sighting of an eastern cougar was in 1938, it was still listed under the Endangered Species Act in June of 1973 (it was removed last year following the proclamation of its extinction). Known populations of other subspecies of Felis concolor are well documented and continue to occur in the western and southwestern states. At this time, the only recognized breeding populations of cougars in the eastern U.S. is in southern Florida, referred to as Florida panthers of the subspecies Felis concolor coryi.

Although the last confirmed sighting of an eastern cougar was in 1938, it was still listed under the Endangered Species Act in June of 1973 (it was removed last year following the proclamation of its extinction). Known populations of other subspecies of Felis concolor are well documented and continue to occur in the western and southwestern states. At this time, the only recognized breeding populations of cougars in the eastern U.S. is in southern Florida, referred to as Florida panthers of the subspecies Felis concolor coryi.

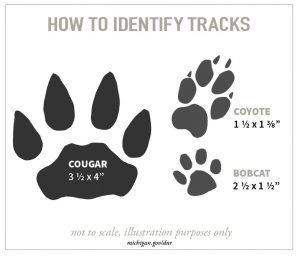

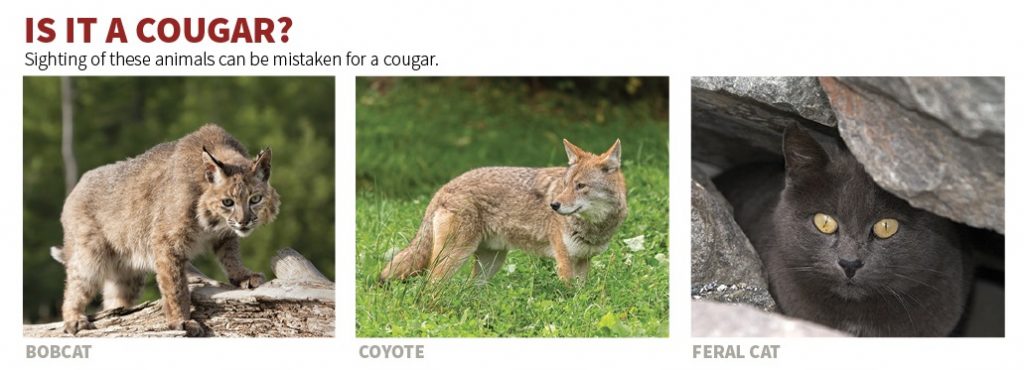

So if the eastern cougar is extinct, then why do folks insist that they still see them? There are a few explanations. First, it could simply be a case of mistaken identity. USFWS

states that the overwhelming majority of reported sightings are of other animals that look similar to a cougar when glimpsed at dusk or running through the woods. Usually, they are bobcats, large feral cats, coyotes, and even dogs when the sightings or photographs are closely inspected. As many as 25% of the photographs the Virginia Department of Game and Inland Fisheries receives of alleged cougars are of black house cats, while cougars are predominantly brown.

It’s not to say, however, that there haven’t been confirmed sightings on the East Coast. Just this past December, the Tennessee Wildlife Resources Agency verified a cougar sighting in Humphreys County. It was the first one to be verified in Tennessee in over 100 years. Prior to that, the Cougar Network reported confirmed sightings (ranging back to the 1990s) in Maine, Vermont, Quebec, and New Brunswick. Additionally, there are verified reports of populations in Arkansas and Louisiana. However, the most exciting proof came in 2011 in Connecticut, when a road kill animal turned out to be an adult male cougar. Genetic testing concluded that he was from a population in South Dakota. Hair samples collected by state officials in New York showed that the same individual had passed through their state, which led biologists to conclude that the animal had travelled over 1,800 miles.

With the exception of the Connecticut case, confirmed cougar sightings do not mean the eastern cougar is no longer extinct. These sightings are most likely the result of an intentional or accidental release of a captive animal, potentially of another cougar subspecies, obtained either legally or illegally via the exotic pet trade. When physical evidence is obtained by officials, DNA results show a genetic profile from South American or western populations, not of the eastern cougar. This finding is a result of research conducted by USFWS that assessed over 100 reports dating back to around 1900. The likelihood that tame cougars, brought up in captivity, could survive and reproduce in the wild is highly unlikely. Therefore, verifiable sightings can occur on the East Coast, but they don’t prove that breeding, stable populations of cougars exist in our region.

“Cougars can coexist with humans, but they need large undeveloped areas to live,” said Tavis Forrester, former Conservation Biologist for the Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute and current Wildlife Research Biologist with the Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife. Male cougars have incredibly variable ranges, but research shows that they require large territories, usually 10-500 square miles. Female cougars have a smaller territory size requirement, but both sexes’ ranges are dependent on food resources in conjunction with habitat quality and diversity.

USFWS states that the overwhelming majority of reported sightings are of other animals that look similar to a cougar when glimpsed at dusk or running through the woods. As many as 25 percent of the photographs the Virginia Department of Game and Inland Fisheries receives of alleged cougars are of black house cats.

The USFWS currently has no plans to reintroduce any subspecies of the cougar into the eastern region of the U.S., and many state wildlife agencies are adamantly opposed to the idea. Forrester goes on to say that, regarding reintroduction to the East Coast, “The lack of large forested areas would be hard, but there are some suitable habitat areas in the East, especially in upstate New York and other areas. The problem would be maintaining breeding populations since dispersing males could be shot or hit by cars and isolated populations might have inbreeding depression.” The abundance of white-tailed deer (which was the eastern cougar’s favored prey) would provide an ample food source if cougars were able to withstand the other human-induced mortality factors and lack of suitable habitat.

While it is possible that western populations could continue to move east (as evidenced by the road kill cougar in Connecticut), there are mortality pressures, habitat fragmentation, and human-induced challenges that new populations would face, making their survival extremely difficult. The Virginia Department of Game and Inland Fisheries has not been able to confirm any reported sightings in our state due to lack of physical or photographical evidence. Therefore, the agency maintains that cougars are extirpated from Virginia. As long as claims continue to go unsubstantiated, the ghost cat will remain a mystery.

Did you know?

- Cougars do not roar! Lions, tigers, jaguars and leopards do. Cougars peep, chirp, putt, moan, scream, hiss, and growl.

- Their skeletons are incredibly flexible, which is what helps them to be such incredible predators. Much of their body actually consists of muscle, not bone. It is said that a large shoe box can fit the complete skeleton of an adult cougar.

- Cougars have round pupils, unlike our house cats, which have elliptical pupils. This gives house cats excellent night vision, but round pupils allow cougars to hunt during the day or night.

- There have been more confirmed sightings of alligators in Pennsylvania than cougars. (Source: Pennsylvania Game Commission.)

Leave a Reply